Ann-Sargent Wooster on

Wolf Kahlen

The technical problem of preserving things that happen in time, a specific time, and have survived through ever-changing technologies that could only have been imagined when the work was made, becomes an act of memory and desire.

Why do we have video art? Wolf Kahlen is emblematic of the evolution of the whole field. Looking at the DNA of something you might profile on ancestory.com, you find several etymologies for the form. On one level, it evolves suddenly from the appearance of the first personal portable video cameras (the Portapack). As Nancy Holt once said, it was very exciting to shoot something in the morning and show it to your friends in the evening. Of course, there were profound limitations by our standards. Videos were in black-and-white and there was no editing or sound. Projects were usually the length of the videotape. Sections could be indicated by in-camera edits—stopping or pausing the tape—which in Kahlen’s hands are pockets of static separating things. He has more of these kinds of edits than was common at this time. He also uses handheld titles and credits—just a piece of paper in front of the camera.

Wolf Kahlen, exhibition 25 Video-Arbeiten – Zyklus Angleichungen, with a video tent (center), Haus am Lützowplatz, Berlin, 1975, © Wolf Kahlen, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Video art developed in the early 1970s, when the phrase “painting is dead” was frequently heard. Video became an alternative visual medium that allowed both abstraction and realism. It was a time when performance art and process art were becoming common. Video art could be about the process of the medium, such as Joan Jonas’s Vertical Roll. It could document performance—an action occupying the length of a videotape. It was most commonly used as a self-reflexive mirror. You could perform for the video camera, or in Kahlen’s case use the camera as documentation (or mirror) of an activity, such as a woman washing her hair. Part of the history and survival of video art is the preservation of the work through all the structural changes of the medium, from reel to reel, to 1/2”, beta and VHS, 3/4”, 1”, and finally digital. The newness of personal video in the 1960s has been superseded by advancing technologies that allow editing, special effects, and complex audio. The early formats are unwatchable unless they are ultimately translated into viewing modes of today. What you can do today, with your handheld computer—the smart phone—is unimaginable from the perspective of the first generation of video work, which Kahlen is part of. Indeed, these early videotapes are about ideas: “let’s see what herding sheep into letters looks like,” or a woman washing her hair, for example. Video art liked to believe it had arrived sui generis, without a history. But in the course of my writing and research I found that it did have ancestors, especially in abstract film of the early twentieth century. It was also an expression of Zen Buddhism, Fluxus, and the experimental music that Nam June Paik practiced before encountering video. Most artists and curators liked to act as if that were not true. Their preferred ancestor was broadcast television. They liked the idea of the little radical folk against the big broadcast giants. They acted as if the people had broken down the gates and stolen the prize. This was a time of radical politics and lifestyles. To some extent, this is true: taking a corporate medium and turning it into a personal artistic form is true.

Schafe, 1975, video stills © Wolf Kahlen, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Video art gained legitimacy when museums and galleries chose to show it. Although there are ways to sell it, video art doesn’t give you the same kind of unique saleable objects like paintings and sculpture. Often, the choice to be involved with the exhibition of video art was a radical one on the part of curators. They kept their mainstream, essentially conservative, jobs and could attack the establishment from within. To keep video art from vanishing like quicksand, museums have bought video art and installations. There are archives of video art such as this one. But what makes us know about video art and incorporate it into the living history of the fine arts? A painting like Leonardo’s Lady with an Ermine is less well-known than the Mona Lisa. Being in Poland, the former is not as easily seen as the Mona Lisa. But it is a painting and there is always the possibility to circulate the photograph. Video art also survives best when there is an iconic photograph from a work, such as an image of Wonder Woman. The importance of striking, iconic photographic documentation is something Marina Abramović learned with great success. Some of Kahlen’s works, such as S.C.H.A.F.E. (Sheep), benefit from photograph documentation. The photograph is not the work itself, but it makes you want to look up the work and see it. Time-based media have a particular problem when it comes to saving and seeing them. For his 75th birthday, Kahlen gave copies of all of his 164 videotapes to the WRO Art Center in Wrocław.

Wolf Kahlen with Allan Kaprow, ADA – Aktionen der Avantgarde, Akademie der Künste, Berlin, 1973

When he was interviewed at his retrospective “Videotapes 1969–2010,” Kahlen said, pointing at a computer, “I can get all of my work in this one box. How do I take them out so you can see them again?” He pointed at his video sculpture Chörten Digital, a 3D light sculpture in a pointed cone-like shape, and said, “That is one of the ways.” There is a spiritual underpinning to Kahlen’s video work. I think he would be happy that when I did a Google image search for him, a picture of the Dalai Lama showed up. More than thirty years ago, I wrote in the Village Voice: “He is less well-known than he should be.” That is still true, at least for an American audience.

Wolf Kahlen, Wurfbilder – Woolwich Ferry, 1972, installation under the ceiling of the Gallery House, London, 1972, © Wolf Kahlen, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

S.C.H.A.F.E. (Sheep), 1975: The video pioneer Nam June Paik said oil paint and brush would be replaced by the cathode ray tube. Kahlen doesn’t do a painting of sheep; he has his two dogs and a shepherdess-seduced herd of sheep spell out the word “sheep”—SCHAFE in German—letter by letter. He puts oats on the ground in the shape of each printed letter, one by one. The sheep are herded into the oats and, while eating them, they make the letter with their hot wooly bodies. They are then herded out. They attack each letter differently, probably because of the letters’ shapes, but their behavior also changes according to their position relative to the letter. They like to eat the top part first and then its legs. There are also bits of sheep drama to look forward to. For several letters, two males fiercely butt each other in the horns. At one point, a Greek chorus develops, with one or more sheep saying BAA…BAA…BAA and another group replying with a nasal AHH…AHH…AHH in a contrapuntal rhythm. The next letter is spelled out and attracts the sheep. There is charm in this piece. Who doesn’t like sheep? In general, the work is about formation and dis-formation. We meet Franz, Josef, Olga, Seline, Veronica, and 106 other sheep herded by the shepherdess Dagmar Maria Spindel.

Poster for the exhibition Wolf Kahlen. Arbeiten mit dem Zufall den es nicht gibt at the Neue Galerie – Sammlung Ludwig, 1982/3

The work falls under one aspect of Conceptual Art concerned with language and meaning. The closest work to Kahlen is Joseph Kosuth’s Meaning series. In One and Three Chairs, he presents three forms of the same thing: an actual chair, a life-size photograph of the chair, and the dictionary definition of a chair pasted on the wall. Kahlen’s work doesn’t seem as didactic because it involves living beings and change. What is a sheep? We see them form letters one at a time, naming their species. As the letters go on, the sheep change the letter forms from block letters to cursive because they have eaten all the grass underneath. They don’t know what they are doing other than being herded to eat oats they don’t know are letters. Their actions, although choreographed by the artist, are a manifestation of how sheep naturally clump and move directed by a shepherdess and dogs. Sheep are famous for grazing, for long-term dedicated eating where they consume the grass down to its roots. Here, this kind of extreme eating (which has been known to destroy national economies) impacts the piece visually. The first letters are robust block letters. By the end, the grass under the oats has been over-chewed and turns the print letters into cursive. The piece ends when Kahlen walks across the empty field diagonally, accompanied by two dogs.

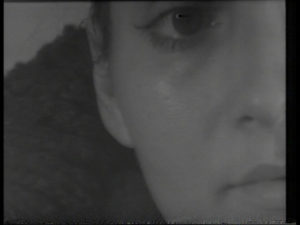

I can’t get hold of her: Angleichung X, 1975, video stills © Wolf Kahlen, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

I can’t get hold of her: Angleichung X, 1975: This piece reminds me of the Zombies song She’s Not There. The goal of the video seems to be about the impossibility of capturing a love object. The camera seems male, so we see a man looking at a woman and using a camera to “touch” her face. She seems to ignore the “gaze” of the camera as it explores her eyes, lips, eyes, nose, and mouth, all portals to the senses. The video ends with a fixed focus on her ear, suggesting the video-maker wants her to hear what he is saying. In this silent black-and-white videotape he is denied this final access. At its core, the video is like a painting of a beautiful woman he desires. By substituting the camera for paint and brush or a photograph, the artist leaves us with a fractured surface happening in time. The medium enhances his core feeling of rejection even more strongly. Old videotape is hard to preserve, and this one now has the glimmering platinum quality of an old daguerreotype that is fading.

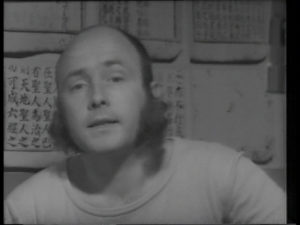

Ich kann sagen, was ich will: Angleichung IX, 1975, video stills © Wolf Kahlen, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Ich kann sagen, was ich will: Angleichung IX, 1975: The ancient story of the Tower of Babel reflects the modern condition—a globe filled with people speaking many different languages. In this work, Kahlen devises a way to express the difficulty of basic communication, interpersonal knowledge, and intimacy. When you first encounter the piece, you might assume it is broken. We see Kahlen talking in front of a wall of Asian characters. Although we can’t hear what he is saying, the sound of occasional coughing lets you know the silence is deliberate. After two and a half minutes there is a break and Kahlen is back at a different time. His lips move, but the words do not connect with the lips, so lip reading is impossible. The separate voice insistently seems to want to tell us something, saying the same thing in different modalities. He is most likely saying in German, “I can say what I want” over and over again. But if you cannot understand what is said, there is a sense it may well be gibberish. The work shows us what the failure to communicate feels like.

Haarewaschen: Angleichung VII, 1975, video stills © Wolf Kahlen, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

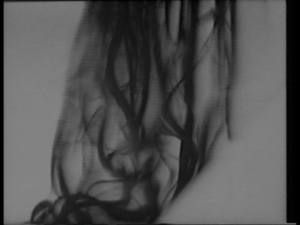

Haarewaschen: Angleichung VII (Hair Washing), 1973: In the seventeenth century, artists started making ordinary people the subject of their work. Often, it is a woman working, such as in Vermeer’s The Lacemaker. Over the passage of time, a subset of genre art emerged in which the artist peeked almost like a voyeur at a woman performing a mundane action concerned with grooming. Degas’s late paintings/pastels and plasters of women engaged in intimate acts of washing are examples of this. Early video was often task-oriented. Here, we see a woman with a chignon so perfect it looks like a hairpiece. She takes out the pins holding it and it is revealed that she has really long hair. Hair always has sexual connotations, which is why some religions want women to cover their hair. In this black-and-white video, the unwinding of the hair is not meant to be wildly provocative, but it is sensual. The rope of hair has echoes of the fairy tale Rapunzel. The woman leans over and washes her hair in a bathtub. The process of shampooing and rinsing her hair twice renders it an anonymous mass of wet material, like cloth. At the final rinse, she displays the vastness of her hair, and as the camera examines it, it becomes a material from the natural world, like the roots of trees (Daphne’s toes in Bernini’s sculpture Daphne and Apollo). This waterfall of curving lines combines the serpentine strands of hair in Mucha’s Art Nouveau posters with their arabesques and the “hair-like” strands that were a feature of Eve Hesse’s work. The woman’s face is upside down at times, giving the image a surreal feeling. Susan Sontag noted that one of the things photography did to movement is transform it from a continuum to a series of discrete objects. Here, Kahlen takes the act of one woman washing her hair and creates an evolving architectural form.

Lichtverlust: Zeit-Raum-Segment, Angleichung IV, 1973, video stills © Wolf Kahlen, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Lichtverlust: Zeit-Raum-Segment, Angleichung IV, 1973: This very dark black-and-white videotape is set indoors looking down at a wooden floor. We hear a person walking on a wooden floor—the sound of footsteps and creaking floorboards. The bouncy camera roams and shows the viewer patterns in the parquet flooring, seeking and finding well-made dovetails. The narrator says, “I go with the camera to search for crevasses …” Infrequently, we see round white spots of light—one, two, or three. These are pinhole-small luminescent diodes installed in the gaps between the wooden floor tiles. This is an early minimal work playing with the most basic materials of the medium. It was originally shown as a kind of installation at the Academy of the Arts in Berlin. Kahlen hoped that visitors to the otherwise empty hall would have a feeling of mystery and dancing in space.

Immer wieder anhalten: Angleichung XV, 1975, video stills © Wolf Kahlen, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Immer wieder anhalten: Angleichung XV, 1975: The viewer is situated in the driver’s seat of a car, looking through the windshield while driving on a two-way street. The radio occasionally plays “… to love again,” while the camera bounces around, creating a sense of vertigo and fear. The fear lies in the feeling that the car is in the hands of an unstable person and could crash into another car at any moment At times, the car seems to be pulling up to a white rectangle. You get a sense of home and the concomitant sense the car will stop. It doesn’t. It backs up and returns to its wild ride. This is a simple idea that relies on the bounciness of a handheld camera, but its use in a car in this way is unusual against the backdrop of other video work done at this time. Cars and early video did not generally go together. Who knew that such a simple device could provoke strong feelings such as “We’re going to crash!” or “I’m going to die!”? Although self-driving cars had yet to be invented when this video was made, it is a good argument for them.

Körper – Horizonte, 1980–1981, video stills © Wolf Kahlen, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

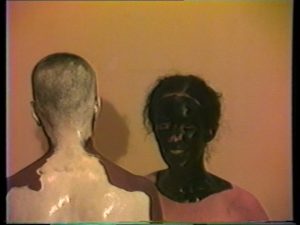

Körper – Horizonte, 1980–1981: We are presented with two nude women, one black and the other white. They are leaning against a white wall with a chair rail. We are given to understand that we are in Brooklyn. The camera’s focus is a bit harsh, almost like these women are specimens pinned to a board. They have been solicited to enact a project in which they examine their own bodies in stages to discover the parts they can’t see. These unseen areas will be painted the opposite color of their skin. One woman says she has been in a nudist camp recently and has seen that bodies come in all shapes and sizes, and the other says she has only been using a tiny mirror lately. One mother asks, “Why did a German come from so far away to paint my daughter?” That is a good question. These two young and attractive women begin the process of self-examination. They examine areas in stages and what they can’t see is painted. They say individually, “The parts of my white body I can’t see were painted black” and “The parts of my black body I can’t see are painted white.”

Wolf Kahlen, Körper – Horizonte, 1980–81, © Wolf Kahlen, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn; at the right side of the image: Ann-Sargent Wooster

Although there is an element of body painting here (think of Yves Klein’s Living Brushes) combined with traditional body painting such as found amongst the Nubia or Yoruba, as the women proceed, unusual shapes appear. One woman’s unseen parts are based on triangles, while the other has the meandering edge of a country or state whose border is a river. What we see here is a personal map-making, or what has been called auto-geography. The main difference between Kahlen’s work and others working in this terrain is that he is using “models.” Much of the work that involved this kind of intense gaze entailed the artist using a camera and monitor to document himself performing an action, meaning the artist was both the subject and object of the work, in a closed system. Although the models’ exploration is unique, they are ultimately Kahlen’s performers. A voiceover amplifies a murmured background. One woman says, “I have never been asked to see my elbow before. […] If you can’t see something, you use another sense.”

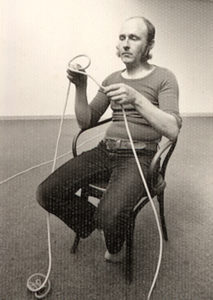

Wolf Kahlen, script for Körper – Horizonte, 1980; Wolf Kahlen performing Tau, 1973; production of the work Wurfbilder – Mistlau/Jagst*, 1972–74 © Wolf Kahlen, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

There are two parts to what is going on. We are intimately watching a woman while she examines herself. This can be a lot like Degas’s late pastels and small sculptures of women intimately involved with their bodies without a witness. But the act of painting on the body shifts this reflection to another category. The women say, “I feel like I’m carrying two persons within me—the one I know and the one I don’t know.” They compare the appearance of the paintings of the areas they can’t see on their backs, as the negative shapes become positive ones, to birds’ wings and the furry hide of a spotted pony. Considering Kahlen’s background in photography, it makes perfect sense when the women say, “People in history have tried ways to know their bodies using mirrors, photography, and video.” The project ends when the women paint their heads and faces. Only the white woman turns around, and we see her in black face. It makes you wonder what it would have looked like if we had seen both of them simultaneously—in black face and white face. This finale brings up issues of race that are still relevant today. As the tape says, how can you know somebody (else) if you don’t see yourself completely?