Sigrid Adorf on

telewissen

The Trio Sonata in Video by the group telewissen is an early multichannel video installation in which three tapes of around twenty minutes each are shown in parallel on three screens. The first version, for the exhibition Feldforschung (Field Research), curated by Wulf Herzogenrath in 1978 at the Kölnischer Kunstverein, was declared by the group to be an “initial contribution” to their project Video-Sprache-Family of Man in Video, conceived as an international communication project. Uncommented video recordings of everyday life, edited pieces from earlier recordings by the group on the themes of leisure time, order/programs, and work were to be sent to different addresses overseas with the aim to get others to do the same, so that thanks to the resulting exchange the world would in fact be experienced as a “global village” (Marshall McLuhan): “For this tape, communicating with language or translation should not be necessary. Understanding takes place solely through watching and listening; the viewer is to be a self-reliant eye-witness, thinking and judging for him/herself.”[1]

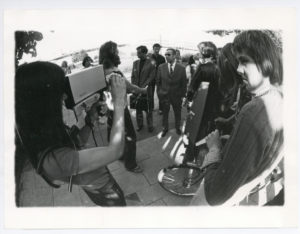

Telewissen at documenta 5 in Kassel, 1972, photo: Ernst Steingässer

First movement: Germans and their leisure time, second movement: Germans and their programs, third movement: Germans and their work

Labeled movements, the three tapes were shown on small television sets—back then still cathode ray tubes, and so directly referring to the television consumption dominant in everyday life.[2] All three parts begin with the opening title Trio Sonata in Video (I–III): written directly on the “tube” with a dark felt pen, the title was filmed and reshown directly on the screen, creating a tunnel-like “picture-in-picture” feedback effect.

Trio Sonata in Video, Deutschland, Deutschland, 1977, 1. Satz: Freizeit, video stills © telewissen

The first movement (“Germans and their leisure time”) begins with scenes from a party marquee in which a swaying, loudly singing crowd is celebrating winning the World Cup in 1974. Close-ups of individual figures switch to wider views of the enthusiastic crowd; the camera seems to be taking part directly, without any focus. Shots of youths on bicycles follow, and then people mowing lawns, pruning hedges, shoveling coal, etc., until the camera “goes” to a bar (literally goes, the shot is from entering the premises) and there, similar to the opening, single figures at the regulars’ table and dancing are filmed alternatively with a view of the whole room. Then come young men head banging, a woman moving as if in a trance to electronic sounds, and diverse shots from discos. The tape ends with a small band recording a popular song (“Monia”) in a studio; the song continues as the camera shot roves through the streets of a small town with a coal mine and power station in the background.

Trio Sonata in Video, Deutschland, Deutschland, 1977, 2. Satz: Ordnung, video stills © telewissen

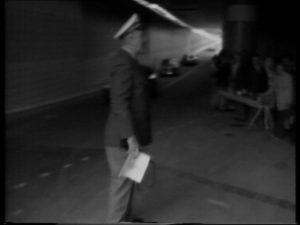

The second movement (“Germans and their programs”) begins with a quartered split screen that represents the television reality of West Germany in the early 1970s—two stations, the ARD and the ZDF (first and second public broadcasters), show a mixture of entertainment (sports: boxing, crime: mugging), traffic reports, and news, while popular hits like “Ein bisschen Spaß muss sein” (“We all need a bit of fun”) are to be heard. In the following sequence, a policeman with a walkie-talkie is shown in an underpass, shooing away cyclists, holding back curious passersby, and directing traffic. Other sequences show a police band in a city center, demonstrators in front of a university building, and an agitated man who is refusing to accept the detour police are telling him to take. It all ends again with the split-screen sequence in which now cartoon segments, clownery, advertising, and one of the “Mainzelmännchen” (the ZDF mascots) form the conclusion to the song “Jetzt ist Feierabend” (“Well, that’s it for the day”).

Trio Sonata in Video, Deutschland, Deutschland, 1977, 3. Satz: Arbeit, video stills © telewissen

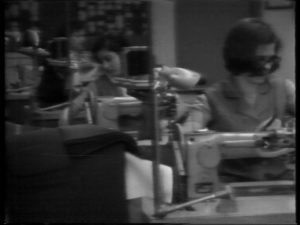

The third movement (“Germans and their work”) begins in a car plant (BMW) where workers are shown fitting side mirrors, polishing fixtures, installing engines, etc. After around three minutes, a child carrying a school cone is accompanied by the camera from home to the classroom on his first day of school. Screenshots show individual children standing around and waiting. This sequence of still images is set to a solo guitar that continues to be heard when the pictorial level switches again to moving images. Back to the car plant: workers embossing sheet metal, one looking challengingly into the camera, which then zooms in on him and tries to get him into focus; things move on, from the bodywork to the paint shop, where the painters wear gasmasks and protective overalls. Cut: switch to a protest march, which is accompanied on its way to the city center, chanting: “Down with the RVO!” There follows a sequence with shots from a children’s room, the kids playing and romping about. The filming of a role play exercise forms the conclusion; outside on the street, an old lady unsuccessfully objects to government plans to demolish her house to build a new road. Three singers with guitar play the “East Tangential Blues.”[3]

Telewissen at the Videotage at the Neue Galerie – Sammlung Ludwig, 1977

„Communication is an art”

Wo Fernsehen aufhört, fängt Video an (Where television ends is where video begins): in 1976 the first and only self-published monograph on the work of the group telewissen is released. Today, with its propositional ring, the programmatic title reads like a snapshot capturing the specific mixture of ideological critique, media euphoria, pedagogic idealism, and activist élan that was so characteristic of the revolutionary mood among various media groups in the early seventies. Herbert Schuhmacher, protagonist of the group telewissen, which was founded in Darmstadt in 1970, formulates this at the outset of the book:

Since the beginning of the century, the wool’s being pulled over our eyes, in images and sound. […] Something similar happened after the invention of writing. For hundreds, for thousands of years, rulers and their scribe slaves exploited the superior medium of preserved language to control majorities. […] We don’t have to wait centuries to be allowed to do for ourselves what film and television are showing us today. Each and every one of us can start now. We show here how people talk with people through video, how they can reach a better understanding through the new medium.[4]

Telewissen, recording during the Videotage in Aachen, 1972, photo: Sepp Linckens/ Zentralarchiv Aachener Zeitung/ Aachener Nachrichten

This is a defiant but seriously meant anti-elitist statement, the form and content of which today, forty years later, seem as anachronistic as they do pressingly topical. The work of the group telewissen recalls an emancipatory promise that has not been delivered on by another medium either, namely the internet. In the seventies there was a greater affinity between the fields of sociology and the arts, emanating from the social movements of this period (student movement, anti-Vietnam, feminism, trade unions, civil rights, etc.), and with it a corresponding mixture of approaches. “Journalists, engineers, students, pupils, graphic artists, sociologists, and pedagogues” are cited by the group in 1978 as the “alternating members and contributors” in its self-portrayal for the Feldforschung project of the Kölnischer Kunstverein. The group mainly worked as an anonymous collective, even if Schuhmacher was regarded as the main figure ever since the 1976 book, in which he is named as editor together with telewissen.[5] In 1972 telewissen took part in documenta 5 (Questioning reality – pictorial worlds today) and filmed people in front of the Fridericianum, with the images shown via a direct feedback on screens positioned underneath the open back of a Volkswagen van. In November of the same year, telewissen continued their “communications experiments” at the first Video Days held by the Neue Galerie in Aachen and invited visitors to try out the new medium themselves and make their own recordings.[6] Video was considered to be looking in a mirror, in both the literal and figurative senses, but moreover definitely in the informative political sense, as a “taking stock”[7] of the times: “You can see yourself on the television screen and react. One of many scenes we register with electronic camera and videorecorder: a mirror image, self-portrait in a new medium—basis for critical analysis.”[8]

This inquiring gesture defined the work of telewissen. By working with video, such a gesture could generate possibilities to directly mirror everyday life and create situations to be reflected on. This was a gesture that was not out to explain things but to create with great restraint and discretion situations that reveal how something functions. The cut, the montage of older material for the Trio Sonata, remains explicitly unruffled. No expressly narrative camera work takes place, except for when a zoom sometimes accentuates individual figures, making them available for more detailed consideration. Tools and techniques for subsequent editing are only seldom used, so that overall a strictly documentary tone characterizes the material shot, which has the look of being left in a rough-draft version and represents the aspiration of the group to let what is depicted show itself. Instead of obeying an aesthetic interpretative logic, the videos follow a sociological thread: “We use video as a means to acquire knowledge and engage in communication, and wish to contribute to discovering new aspects of reality. With sequences that move, sound out, but are only mosaic-like details, we contribute to the scientific study of human beings. Raise consciousness for everyday life as an experience and make it visible as history. Create a basis for better communication. […] Replace the director with reality, largely reduce pictorial manipulations.” [9]

[1] Feldforschung, exh. cat., Kölnischer Kunstverein 1975, 73.

[2] Gregor Jansen emphasizes in Deutschland auf allen Kanälen. Das Fernsehen neben dem Fernsehen that the still unusual presentation form of a multichannel installation created a situation enabling those watching to “put together their own film in their minds.” In Record again! 40 Jahre Videokunst.de Teil 2, ZKM Karlsruhe, 292–293, here: 293.

[3] The east tangent in Darmstadt was a large city-planning project typical of the time; it aimed to channel the streams of commuters and relieve some of the pressure on other roads in the city center. The resistance captured on video by telewissen can be seen as evidence of the debates which in some cases (for example Bremen) succeeded in preventing further waves of demolition for the building of elevated roads.

[4] In Wo Fernsehen aufhört, fängt Video an (telewissen, Herbert Schuhmacher, Darmstadt 1976), pictures of the first video experiments in Darmstadt from December 1970 and February 1971 are documented (9–12). In recent publications, however, it is claimed that Herbert Schuhmacher founded the group telewissen in 1969 (see for example https://www.medienkunstnetz.de/kuenstler/telewissen/biografie/).

[5] Klaus Dumuscheit and Rolf Schnieders are also named as members in the catalogue Record again! 40 Jahre Videokunst.de Teil 2, ZKM Karlsruhe 2010, 293.

[6] “Neue Galerie der Stadt Aachen. Video-Woche: Eigenproduktionen,” in: aachener studentenzeitung asz, no. 15, November 15, 1972, 5. (https://www.mao-projekt.de/BRD/NRW/KOE/Aachen_VDS_Aachener_Studentenzeitung/Aachen_VDS_Aachener_Studentenzeitung_1972_15.shtml, accessed March 3, 2017) and 10 Jahre Neue Galerie – Sammlung Ludwig, ed. Neue Galerie – Sammlung Ludwig in cooperation with Verein der Freunde der Neuen Galerie, Aachen 1980, n.p.

[7] asz (see note 6).

[8] telewissen-gruppe, Darmstadt, in: Befragung der Realität. Bildwelten heute, documenta, exh. cat., Kassel 1972, chap. 12, 20

[9] Ibid.