Doris Krystof on

Marcel Odenbach

In 1977, Marcel Odenbach, twenty-four at the time, named several reasons for his artistic decision to work with video, which now, at the beginning of the twenty-first century, almost seem like a historic manifesto. Expressed in incisive sentences, the artist, still enrolled at the RWTH Aachen in architecture, explains “why I work with the medium of video: because video merges three elements, a) the image, b) action sequences, c) the sound, to demonstrate the power of technology and progress in society; because the television image tends to match today’s visual habits more than the panel painting; because television, as a way of passing time with a high degree of entertainment, has triggered social, i.e., political changes ‘in large measure’; because media analysis and critique has become a pivotal issue in our society; because I can address, theoretically, an even greater circle of recipients than museum visitors; because my visual representation can then no longer be used as an adornment and representative wall decoration; because the art loses a part of its character as a commodity; because I can focus on more comprehensive alternatives!”[1]

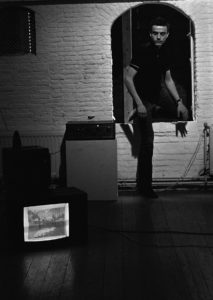

Marcel Odenbach, video performance Einfach so wie jeden Tag oder sich selbst bei Laune halten, De Appel, Amsterdam, 1978, © Marcel Odenbach, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, photo: Klaus vom Bruch

Just a few decades later, Odenbach’s clear-sighted explanation had been completely integrated into the general, international view on visual art. Today, the rapid development of the electronic media continues apace and the spectrum of contemporary art is inconceivable without them, while the moving images they project so largely into space are enormously popular amongst the public. If in the pioneer years of video art emphasis was placed on its similarity to television, different tangents followed, with artistic explorations involving cinema, documentary, and finally digital imaging. The extensive oeuvre of Marcel Odenbach, who was born in Cologne in 1953 and studied architecture and semiotics before turning to performance and video art, is a perfect foil for plotting this development of moving or time-based images. The approach proclaimed by the young Odenbach, progressive and critical of the media, turns up again in later works, for example In stillen Teichen lauern Krokodile (Crocodiles lurk in still ponds, 2003–04), a dual-channel video installation on the Rwanda genocide, or Disturbing Places (2007), a film of a trip to India operating with alienated narratives. Odenbach has adhered to his early decision to work with video, explaining: “The choice to work in the medium of video was, in part, a political one. This political dimension has exerted a strong influence. For example, I observed in Africa that young artists desperately wanted to work with the various new media, because these can function subversively. I see in this a similar motivation to one lots of artists had at the beginning of the 1970s. Here, and today, video has lost this function slightly, but I still believe that the medium as such, and also because it is available to everyone, can still play a powerfully progressive, enlightening role.”[2]

Looking back at Odenbach’s beginnings, for all the continuity evident in terms of subject matter, one striking difference is obvious in comparison with his later works—the technology. And indeed, the possibilities today are worlds apart from what once was: with devices easier to operate, they can be used by a far larger community than the unwieldy—and relatively expensive—equipment used to produce video art in the 1970s. For the pioneers of video art, a host of basic technical features of a video camera nevertheless provided the opportunity to pursue interesting artistic approaches, for example instant recording and replay of images, or filming alone, making it possible to work independently without a large supporting team.

In the mid-1970s, Marcel Odenbach bought his first video equipment, and in 1977 the legendary supporter of video art, Ingrid Oppenheim (1924–1986), allowed him to work in the studio of her gallery in Cologne’s Lindenstrasse. Filming and processing the video material thus took place at a much-respected location, attracting great attention at the time. In 1968 a number of galleries moved into a building complex at Lindenstrasse 18–22, including the up-and-coming gallerists Rolf Ricke, Heiner Friedrich, Reinhard Onnasch, and others. Within a few years they became a hub in the briskly developing art trade in the Rhineland, ignited by the first Cologne art fair, the Kölner Kunstmarkt, in 1967, the forerunner of Art Cologne. As Ingrid Oppenheim moved into the rooms vacated by Heiner Friedrich after his move to New York in October 1974, she not only supported young artists with an almost patron-like interest and generosity but also provided the new medium of video with a platform in the middle of this vibrant Cologne art scene. For Marcel Odenbach, Klaus vom Bruch, Ulrike Rosenbach, Sigmar Polke, and many others, Oppenheim’s gallery offered a place where they could produce and distribute at the same time. The adjoining recording studio was not yet fitted with an electronic editing suite, so that all the early videos produced here are “parallel montages,” i.e., images put together into sequences, “edited” solely by turning the camera on and off. For all his propensity towards experimenting with the new technology, the combination of filmed images, their rhythm, the accompanying sound, and the often detailed literary-like titles all contribute to Odenbach’s unmistakable style. The three videos in the collection of the Ludwig Forum Aachen are from Odenbach’s early phase, created in the Oppenheim studio. They usher us into the early work of an artist who, more than any other, represents the development of video art in Germany. Since 2010 professor at the Düsseldorf Art Academy, he is—far beyond the narrower confines of just video art—one of the most important artists of his Generation.

Die Spielverderber oder sich selbst bei Laune halten, Video-Stück, 1977–1978, video stills © Marcel Odenbach, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Die Spielverderber oder Sich selbst bei Laune halten (The spoilsport, or keeping yourself amused, 1977–78)[3] shows in 13 sequences alternating hands in close-up, occupying themselves with a puzzle, and press images from the “German Autumn” of 1977, the series of events ignited by the terrorist activities of the Red Army Faction. The only player is Odenbach, who “keeps himself amused” by playing with number squares, a pin board, or a yoyo. In stark contrast are the news images, for instance those about the kidnapping of Hanns Martin Schleyer by the RAF in Cologne in the summer of 1977, a drama that kept West Germany in suspense beyond Schleyer’s murder in September. Whereas the spoilsports named in the title carry out their terrorist operations in public, the protagonist of the video is engrossed in individual games of skill and dexterity. “Some play patiently by the rules, others attempt to change the game and make their own rules”[4] is one laconic comment on the video, which in the context of the postmodern discussion of those years seems to signify the general loss of credibility of images. Another noteworthy aspect of the specific composition is how Odenbach uses the temporal dimension of the moving image both as a central content-related component and an important psychological factor. The combination of images taken from the current political situation with shots of banally playing around rises in tension as the gestures of the player become increasingly hectic, an impression reinforced by the sound of the clicking Metronome.

Temporal delay and tedious pausing are also key in other early Odenbach videos, already indicated by titles like Abwarten und Teetrinken (1978, Wait and See) or Was ich noch zu sagen hätte, dauert eine Zigarette (1977, What I still wanted to say takes the time needed to smoke a cigarette). Again, moving hands in close-up generate a sense of nervousness. The back-and-forth of the camera being switched on and off brings an additional physical dynamic into play. The process of recording the video thus becomes an almost performative feature of Odenbach’s artistic practice. In 1978 Odenbach staged a performance in the De Appel Stichting in Amsterdam that referred back to the video from the year before. For the performance Einfach so wie jeden Tag oder Sich selbst bei Laune halten (Just like every other day, or keeping yourself amused), the Cologne art critic Marlis Grüterich underlined the temporal moment of suspense and tension evident also in the video, remarking “that following and finally mastering the rules of a game also entails an encapsulating in artistic calm. (…) Side by side and jumbled all together are the images of two groups who playfully and violently limit themselves to their own horizon, convincingly demonstrating a lack of understanding, the lack that is responsible for the harmless dangerous encapsulating of the individual and the deadly social isolation.”[5]

Versteck der Frühen Verbote, 1981–1982, 1977–1978, video stills © Marcel Odenbach, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

The employment of rhythm, tempo, music, and tension, in conjunction with the polarity between individual and society, are also characteristic of the video Versteck der frühen Verbote (Hideout of the early prohibitions, 1981–82),[6] a collage of already-existing film material and self-filmed sequences. Quotes from Brian de Palma’s latest film at the time, Dressed to Kill (1980), and Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960) draw the viewer’s attention to the dramaturgy of the suspense and the repression of sexual desire, a key theme in both movies. The bird trapped in a cage in the first sequence and the final scene with Odenbach’s face, a grid-like shadow cast across it, frame the video. With the haunting minimalistic music of Steve Reich (Music for 18 Musicians, 1976), the set-pieces of cinematographic narration and images of taking stock of a personal situation interweave into a flustered, nervous self-inquiry by the artist, leading Ingrid Oppenheim to observe that the various moments “string together like a horror trip and signal the constant threat humans are exposed to in the world, the dictates and the prohibitive rules of society.” In an interview given in 2012, Odenbach explained his fascination with moving images that interface with the illusionistic machinery of cinema: “The different levels of perception are of particular importance for me. I like to work with a façade, with an image that is not what it seems to be. It’s perhaps a bit devious, I’ve probably learnt this from film, especially from Hitchcock. The veneer deceives and moving closer opens up another world. Perhaps these different perspectives are also a mirror of our current society and politics.”[7]

History, politics, cinema, postmodern theories of simulacrum, music—all this can flow into the videos of Odenbach the semiotician, and another important source of inspiration is contemporary literature. With the “hideout from early prohibitions,” Odenbach directly takes a line from Botho Strauß’s just-published text collection Couples, Passersby (1981), quoting an author who was a lucid theater critic and dramaturge at the Berliner Schaubühne before changing sides and becoming, with plays and prose, one of West Germany’s most successful writers of the 1980s. Strauß soon became embroiled in the vehement discussion about a “new subjectivity” that was raging in West German literary circles, a countermovement to the politically engaged literature of the 1968 generation that shifted the focus to personal dreams, problems faced in private life, and introspection. Another author seen as belonging to the “new subjectivity” was the Austrian Peter Handke, whose work Odenbach drew on more frequently than any other literary source.[8] The video completed in 1982, Der Widerspruch der Erinnerungen,[9] (The contradiction of memories) quotes Handke’s story Long Homecoming from 1979.

Der Widerspruch der Erinnerungen, Video-Stück, 1982, video stills © Marcel Odenbach, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

When adopting from literature, Odenbach is just as predatory as he is with film and musical material, while the practice remains the collaging of elements. Quotes are often used repeatedly, for example Steve Reich’s electronic music is once again to be found in The Contradiction of Memories, now however combined with Vivaldi, J.J. Cale, and Torbusch. As for how the video is actually composed, the stringing together of already-existing and self-filmed images—here once again with a number of Hitchcock borrowings—is joined by a new technical ruse: a gradual fade-in of a black image, beginning from the upper edge, creates an effect that resembles that of a cinematic flashback. The resulting consequences for the dramaturgy and narrative strategy, merely hinted at in the title’s reference to “memory,” are immense and continue from this point on in the visual language of the videos and, in particular, the video installations of the 1980s. Odenbach has repeatedly emphasized the importance of The Contradiction for his work—it marks the threshold to a new development, and it is for this reason that Raymond Bellour has called it a “transitional work.”[10]

Around 1980, Odenbach’s artistic approach discernibly shifted, developing in the context of a tradition of narrative, content-oriented art, and now embraced the aesthetic of films montaged from an astoundingly varied array of sources. Refining his use of collage, he turned to the historical form developed by George Grosz, Hannah Höch, and others, transferring their use of the medium of paper into film and, from 1991, elaborate paper works. With his fragmenting aesthetic, Odenbach tests in his videos the possibilities remaining after modernism to create a narrative art firmly grounded in specific content that is political. Crucial in collage is the cutting technique, for it fits together the contrasting elements to form a new structured whole, dissolves hierarchies, and relies on a viewer with an independent mind, willing to observe, ponder, and think. Odenbach specifically applies the technique of cutting and collaging to time and movement, the constitutive factors of the medium of film, and this enables him to dissolve linear narrative modes and challenge logical causality. The world Odenbach depicts is disparate, heterogeneous, and fragmented. The images function in the same way as the process of remembering. Odenbach’s “medial history paintings” [11] tap into and evoke associative imaginary spaces and elevate remembering, intuitive sensing, and doubting to active forms of knowledge.

[1] Marcel Odenbach, quoted in Slavko Kacunko, Marcel Odenbach. Konzept, Performance, Video, Installation. (Diss. Universität Düsseldorf 1998), Mainz and Munich, 1998, 168–69.

[2] Interview on February 5, 1999 (Hans Belting & Marcel Odenbach), in: Marcel Odenbach. Ach, wie gut, daß niemand weiß, exh. cat. Kölnischer Kunstverein, Cologne, 1999, 58–59.

[3] In Kacunko 1998 (see note 1), 188–191, diverging details are given: Sich selbst bei Laune halten oder Die Spielverderber, 1977, 12’50’’, color, sound production format: 3/4 inch NTSC, production: Studio Oppenheim Cologne. 1985 newly montaged (before then ‘only camera shots’).

[4] Cf. the entry at https://www.medienkunstnetz.de/werke/bei-laune-halten/

[5] Kölner Stadt Anzeiger, September 3, 1978. For the course of action during the performance, see Kacunko 1998 (see note 1), 97ff.

[6] Kacunko 1998, 212 ff and 540: Das Versteck der frühen Verbote, 1981/82, 19’53’’, color/sound, ¾ inch, ½ inch, Studio Ingrid Oppenheim, sound: Steve Reich, Music for 18 Musicians (1976).

[7] Marcel Odenbach, 2015 (quoted from https://www.Museum Ludwig/Ateliergespraech.de).

[8] See the listing of “textural quotes” given by Kacunko 1998, 525 ff.

[9] Kacunko 1998, 216ff and 540: Der Widerspruch der Erinnerungen, video, 1982, 12’56”, color, 13’, ½ inch VHS, ¾ inch, production: Marcel Odenbach and Studio Ingrid Oppenheim, Cologne; musical quotations: J.J. Cal, Vivaldi, Torbusch, Steve Reich.

[10] Kacunko 1998, 216ff.

[11] Lydia Haustein, Videokunst, Munich, 2003, 120.