Ronald Dagonnier on

Jacques-Louis Nyst

I effectively came to painting through Surrealism. I had been strongly impressed by Magritte’s painting, which allowed a complete mental world to be rendered through image. I realized that this whole mental world I held within myself could be expressed with shapes and colors. I encountered Surrealist painting when I was a student. JACQUES-LOUIS NYST, 1972, interview with Léopold Plomteux, 1972, Léopold Plomteux archive

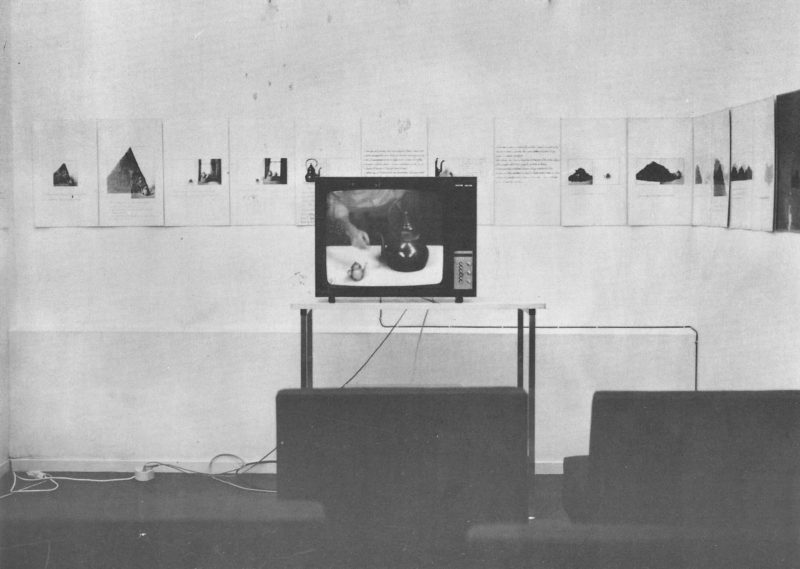

Jacques-Louis Nyst, L’objet, 1975, in the exhibition Belgien: Junge Künstler I, Neue Galerie – Sammlung Ludwig, Aachen, November 22 – December 28, 1975, © Jacques-Louis Nyst, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, courtesy Marc Renwart

Jacques Louis Nyst’s video work can be defined by the need to remodel the various art media he has experienced. From painting to writing, from painting to drawing, from photography to writing and, finally, from the accumulation of all these art forms to what will become his main means of expression: videographic poetry. The stuff of his artistic world is recontextualized meaning, with a focus on image as the key interest: in Nyst’s work, an image is a word and a word is an image. He met Magritte in 1964, who said the following of Nyst: “One of his ideas appears to me as being very good to know: dreaming must not be considered an ‘escape.’ It is a true state in which one finds oneself, no more and no less alive than during a waking state.” As a lover of philosophy, and particularly of the work of Jiddu Krishnamurti, Jacques Louis Nyst constantly isolated objects from their contexts in order to force his viewers to place their interpretations of what they see, read, and feel into perspective. Throughout his life, Nyst constituted a breviary of objects that appear from one video to the next but also in all his other artistic media. These objects—a spade, a hat, a little coffee-maker, an egg, a ladder, etc.—are pretexts that lead us to reflect on the possibilities that an attempt to renew language can offer in a given medium. His first experience with animated pictures came from using a 16mm camera he received as a gift from his father. In 1971, in what is regarded as the first video exhibition in Belgium, he took part in “Artists’ proposals for a closed television circuit” at the Yellow Now gallery in Liège, on the impulse of Guy Jungblut. This video displays a self-portrait in which he drinks a glass of water, live. Nyst initiated the creation of the videography workshop at the Liège School of Fine Arts in 1986.

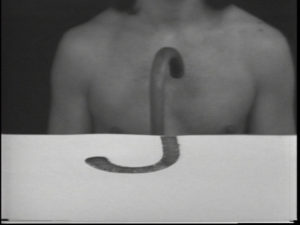

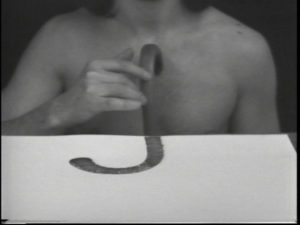

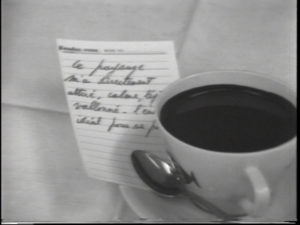

L’objet, 1975, video stills © Jacques-Louis Nyst, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

L’Objet (repeated in the 1977 Paper Parasol compilation), 1974, b&w (color in 1976), Production: Continental Video

In a still frame, an archeologist of the future discovers something that, to us, resembles a coffee-maker. Starting from the status of complete ignorance as to the provenance of this object, Nyst has fun recreating poetry around the dissolution of meaning. He objectively renames the coffee-maker “Germany,” as it is the only written element he can draw conclusions from as to its history. A series of hypotheses follow, through which he attempts to give a meaning to something that is nothing more than a child’s toy.

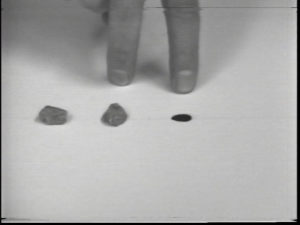

Le tombeau des nains, 1975, video stills © Jacques-Louis Nyst, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Le Tombeau des nains (repeated in the 1977 Paper Parasol compilation), 1975, b&w, Production: Nyst / R.T.C.; U-Matic; archived at R.T.C.

Hélène Parizel, op. cit., p. 85: “Two stones on a blank page, two fingers miming steps, black stains appearing beneath. The commentary is very conventional and one would expect the images to be just as conventional.” Nyst comes back to an idea that is important to his production: the input of touch that does not come through the mind but through direct sensation. He invites us to observe an “absence of narration” which nevertheless shows two stones and black stains formed by the print of an index finger, dipped in paint on a white sheet of paper.

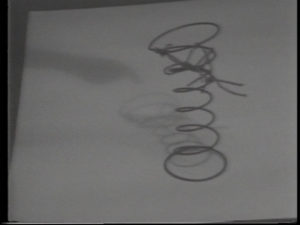

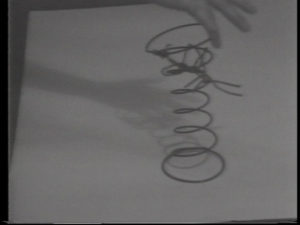

Le robot, 1975, video stills © Jacques-Louis Nyst, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Le Robot (repeated in the 1977 Paper Parasol compilation), 1975, b&w, Production: Nyst / R.T.C. (*); U-Matic, archived at R.T.C.

A hand crushes a bed spring on a blank page. Nyst replaces the sound of crushed metal we expect to hear with birdsong.

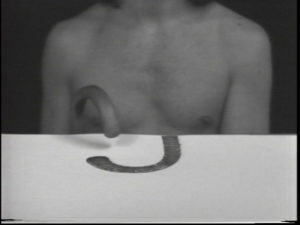

Le cygne et son image, 1975, video stills © Jacques-Louis Nyst, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Le Cygne et son image (repeated in the 1977 Paper Parasol compilation), 1975, b&w, Production: Nyst / R.T.C.; U-Matic; archived at R.T.C.

Nyst starts from the premise that the image of reality is not reality. A cane becomes a swan, and the sign is manipulated until the cane becomes a living object, just like Germany in “The Object.” Here, Nyst transforms a common device into a living being, which he personifies through his breath. The cane’s shadow enables him to stress the following idea: a shadow is not a shadow, a cane is not a cane.

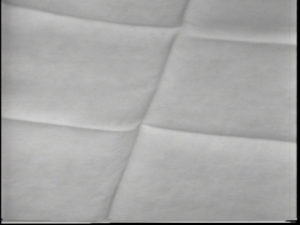

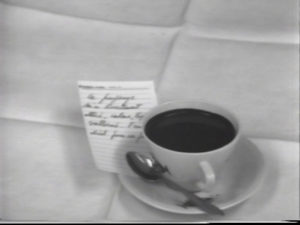

Le paysage, 1975, video stills © Jacques-Louis Nyst, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Le Paysage (repeated in the 1977 Paper Parasol compilation), 1975, b&w, Production Nyst / R.T.C.; U-Matic; archived at R.T.C.

The folding of a white tablecloth forms a landscape when shown in close-up. Nyst reads, with voice-over narration: “This landscape immediately attracted me, as calm and slightly hilly as it is. The ideal place to settle,” He lays a cup of coffee upon it, on which a handwritten note of the text he just read on the voice-over is placed. He then appears on screen to explain how to hunt transparent green hens using a top hat, while imitating the noise made by the green hens. By integrating the text that he previously read, Nyst has fun creating a breach in the storyline, leading us then into his habitual absurdity and derision, thanks to an instruction manual explaining how to hunt green hens.

Le voyage de Christophe Colomb, 1975, video stills © Jacques-Louis Nyst, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Le Voyage de Christophe Colomb (repeated in the 1977 Paper Parasol compilation), 1975, b&w, Production Nyst / R.T.C.(*); U-Matic; archived at R.T.C.

Similar to an “earth-rise” seen from the moon, Nyst films the appearance of an egg on which the word “earth” is written. Audio broadcasts from American astronauts place us as observers of the Apollo mission, diverted this time, to the extent that we are actually observing an egg, two blank pages, and a set square that oscillates like Foucault’s pendulum. Here, Nyst conjures a theme that is crucial to his approach: transforming a mere viewer into a scientist, who yet attempts to find poetry in everyday objects.

*Videograms exhibited in Paris, Musée national d’art moderne / Pompidou, Musée d’art moderne de la ville, and Musée Galliera: “9th Biennale” (19 September to 2 November 1975).

Jacques-Louis and Danièle Nyst, Deux oiseaux chantent, 1982, video stills © Jacques-Louis Nyst and Danièle Nyst, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Deux Oiseaux chantent, 1982, color, directed and produced by D. and J.L. Nyst; U-Matic and Master; archived at R.T.C.

“Two characters question themselves on the bird’s song. One of them declares that it originates from a page of text. The following dialogue evokes a series of images showing familiar objects and the countryside around Presseux—a village beneath the snow. The influence of the winter landscape focuses the conversation on the idea of white and silence. The action slows down. The increasingly calm situation prompts the appearance of the text, causing the bird’s song to appear. Two birds sing 100 x TCHIP TCHIP (i.e., “cheep cheep”). The bird’s song is a good omen for a loving couple.” (Arc Leaflet 1986 / Bio. According to…)

Danièle and Jacques-Louis Nyst, Deux oiseaux chantent, 1982, Namur, 1982, © Jacques-Louis Nyst, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, courtesy Marc Renwart

While pursuing his “Magrittean” search for the possibility of transforming an image into something it is not, Nyst produces a form of self-representation of his partnership with Danièle, appearing in the form of two birds. This video anticipates the future works he will produce, starring Thérèsa et Codca (Jacques Louis and Danièle) as the main characters. Rather than personifying a classical narrative, he exploits the poetic possibilities offered by the visualization of words and their semantic meaning, until they seem absurd. The word “tchip” ultimately appears 100 times on screen. Here, Nyst stages a television set (video art) which he films, and in front of which two birds, he and his wife, watch Tarzan and Jane playing in nature.