Lou Jonas on

Christina Kubisch

Since the 1970s, Christina Kubisch’s work has developed at the crossroads between composition, sound sculpture, performance, and installation. Kubisch did a course in painting at the Academy of Fine Arts in Stuttgart, as well as classical music training at the academies of Hamburg and Graz. She then went on to study at the Conservatory of Music and the Freie Kunstschule in Zurich. In 1974, she completed her training in Italy, studying composition and electronic music at the Milan Conservatory. At this time, she began a collaboration with the visual artist Fabrizio Plessi, whom she had met the previous year at the summer academy of the Salzburg Festival.

Performance at ICC, Antwerp: Emergency Solos, 1975, video stills © Christina Kubisch

After her studies, Kubisch directed Emergency Solos (1974/75), a series of actions for a flutist that combine two different environments: the traditional concert world and the domestic, everyday world. The artist introduces a series of daily objects (thimbles, a condom, boxing gloves, a gas mask, etc.) onto the stage, and all these devices divert the instrument from its original function. The instrument seldom makes a sound[1] and serves more as a tool used to create a range of sound effects. This is particularly true for an action called Private Piece, in which the performer holds the head of the flute to her ear, so that only she can hear the sounds made by her body, amplified by the instrument. All the objects being used produce their own sounds in combination with the metallic texture of the flute. In It’s So Touchy, for example, the percussion and friction of ten thimbles on the surface of the flute create a nervous scraping noise, in stark contrast with the sounds conventionally emitted by the instrument.[2]

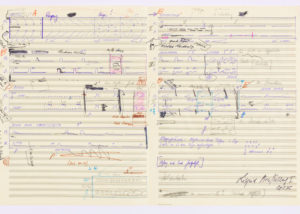

Christina Kubisch and Fabrizio Plessi, score for Liquid Piece, © Christina Kubisch, Fabrizio Plessi; Christina Kubisch and Fabrizio Plessi, score for Liquid Piece for transverse flute, voice, gurgling performers, and water, 1975, © Christina Kubisch, Fabrizio Plessi; Christina Kubisch and Fabrizio Plessi, score for Liquid Piece, © Christina Kubisch, Fabrizio Plessi

The title given to the series Emergency Solos reflects a situation of danger. The danger is faced by the musical instruments, which are sometimes subjected to violent actions, as symbolized by the boxing gloves in Break.[3] This is reminiscent of happenings organized by the Fluxus group, which would end with the destruction of a piano or a cello. Perhaps the feeling of emergency is related to the individual and his ecosystem, as suggested by the use of the gas mask in Weekend? Or would the latter more likely be a reference to a climate of war and its murderous bombings? These objects allow many interpretations and confer a dimension that is both playful and sensual on Kubisch’s musical composition. With these objects, Kubisch breaks with the traditional conventions of both classical and contemporary concerts. Her critique focuses on the gestures and behaviors associated with the female figure in the music world. In an interview,[4] the artist explained that she sought to reveal the condition of women, who are often limited to performing, whereas composers are predominantly men. The relaxed and uninhibited attitude of the performer, who wears a loose shirt hanging above a pair of wide-cut trousers, contrasts with the strict and solemn style of concert apparel. Moreover, during her performance of a Christmas hymn on the flute in Stille Nacht, she repeatedly removes her shirt, stripping her torso bare. This provocative gesture stresses the erotic imagination that female musicians can awaken. Similarly, in Erotica, a condom placed at the end of the flute reveals a certain irony. It is combined with a white sheet under which the artist lies, symbolizing the intimate sphere of the bedroom. The absurdity of the scene is reinforced by the sounds: sounds of inflation and deflation, the skin of the condom deflating loudly, the plastic squeaking or the elastic cracking.[5]

Performance at ICC, Antwerp: Exotica, 1975, video stills © Christina Kubisch

Although Kubisch’s approach is marked by feminism, it is different from that of more radical feminist artists such as Marina Abramovic, Gina Pane, or Valie Export, who have made their bodies into the main object of their claims. Kubisch stages and questions the female archetype through humor, which she orchestrates by using a selection of unusual objects. As such, her work is closer to that of the American artist Joan Jonas, a pioneer of video art who uses objects and costumes as well as scenography to study the female identity.

The Emergency Solos have been presented several times all over Europe, and in Antwerp in particular, after the “Water Art” exhibition that the ICC dedicated to Fabrizio Plessi in 1975. A video recording of the performance was produced for documentation purposes, alongside photographs, drawings, scores, and studio-recorded audio tracks.

Performance at ICC, Antwerp: Liquid Piece, 1975, video stills © Christina Kubisch

It was not until 1976, however, during their work on the Two and Two project, that the artistic duo of Kubisch and Plessi integrated video technology into a wider reflection on space, making it into an autonomous element alongside musical composition. This creation is part of what Christina Kubisch and Fabrizio Plessi called their “video concerts.” The term refers to a practice that combines live musical performance with a visual reproduction of it, using a closed-circuit television system. Two and Two is based on a duality principle, combining the four elements: water, earth, fire, and air. Each of them is symbolized, both visually and audibly, by associations between conventional musical instruments such as the flute or the cello and a series of objects removed from their original context (a fan, a vibrator, a dust mask, etc.). Video appears through the construction of a wall of monitors that broadcast sequences studying certain aspects of the performance. The wall erected between the performers and the audience keeps the latter at a distance. But, in our opinion, the advantage of this arrangement lies not so much in the drawing of a line but rather in the juxtaposition of two spaces. Thus, reality, which is played in the background, is reproduced by the video images in the foreground.

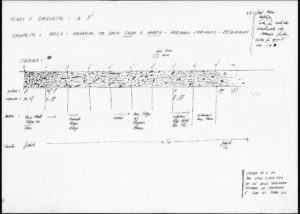

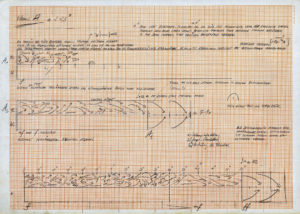

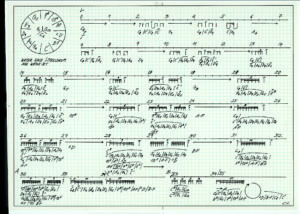

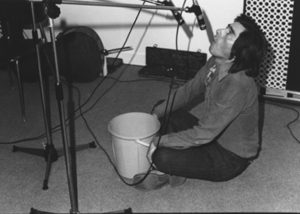

Christina Kubisch and Fabrizio Plessi, score for Water/Face I, © Christina Kubisch, Fabrizio Plessi; Christina Kubisch and Fabrizio Plessi, score for Water/Face II, © Christina Kubisch, Fabrizio Plessi; Christina Kubisch at the recording of Water/Face II, © Christina Kubisch

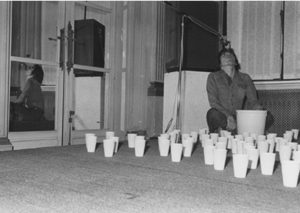

Subsequently, the artists continued to reflect on the layout of their action space through the use of monitors. In Tempo Liquido (1978), Kubisch and Plessi place several pairs of monitors in a circle, creating a space in the center where the audience is invited to observe the details of the action. The performers remain on the side, posted behind a sort of control station, seemingly trying to blend into their surroundings. Just like stage directors, they ensure the show is running smoothly, while the audience plays an essential part in the performance.

Christina Kubisch and Fabrizio Plessi, Water/Face I, 1979, video stills © Christina Kubisch and Fabrizio Plessi

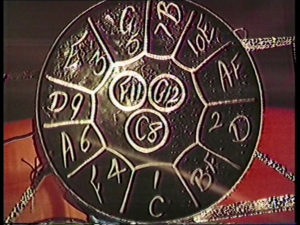

In 1979, the Neue Galerie in Aachen—the predecessor of the Ludwig Forum for International Art—hosted the world premiere of the Water Face video concert. Just like in the two previous cases mentioned, this work is based on the link between sound and image, as well as on the juxtaposition of reality and its reproduction using new technologies. The sound composition consists of two main parts,[6] which both have in common the use of water as a material for sound. The first part is a repetitive melody created by the percussion of a continuous stream of water on the resonating surface of a steel drum.[7] Groups of rhythms are gradually added together to form a loop. Christina Kubisch’s voice is superimposed on this first soundtrack, uttering a text where the word “water” is said repeatedly. The word is associated with a range of verbs referring to a series of water-related activities (watering, welding, fermenting, etc.) on the one hand and, on the other hand, with a set of emotions or perceptual situations: sinking below the water, slipping, being touched, cooling, then reflecting, opening, being transported, abandoning, and leaving. The text is subject to variations. Kubisch’s voice is interrupted several times before resuming its dictation from the beginning. What’s more, after about twenty minutes, the more attentive listener can perceive the repetition of certain fragments of text, thereby creating an echo. Finally, and more typically, groups of words with similar meanings can be identified within the text, but these change as they are repeated and associated with others words.

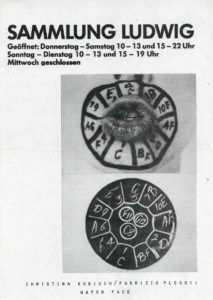

Christina Kubisch and Fabrizio Plessi, script for Water Face, © Christina Kubisch and Fabrizio Plessi; Invitation to/announcement of the exhibition Christina Kubisch/Fabrizio Plessi: Water Face, Neue Galerie – Sammlung Ludwig, Aachen, 1979, © Christina Kubisch and Fabrizio Plessi

As a counterpoint to the music, monitors are scattered around the exhibition space. They alternately broadcast footage of the drum and of Christina Kubisch’s mouth, both in a close-up frame. This change of scale contributes to a curious game of proximity and distance, since the very fact of being placed at a distance from the action enables the viewer to see it close up. Therefore, the viewer can observe and allow himself to be transported by the sensual movements of the mouth in an almost intimate relationship. On the skin, a circle is drawn and split into a series of encrypted symbols that establish a visual correspondence with the musical chords repeated on the drum. The images have their own reality, superimposed on that of the sound environment. They ultimately accompany the real action, which the viewers can contemplate from another point of view.

Christina Kubisch and Fabrizio Plessi, Water/Face II, 1979, video stills © Christina Kubisch and Fabrizio Plessi

With their “video concerts,” Kubisch and Plessi offer an alternative to the classical concert tradition, which requires attentive and linear listening. This is done through a scenographic reflection that combines different types of images, sounds, objects, durations, and spaces.

Sound, like image, takes part in a polyphonic ensemble based on repetition and variation. The multiple screens offer a variety of viewpoints, and this also applies to the treatment of sound, which is multiplied through loudspeakers.[8]

Christina Kubisch, Emergency Solos, ICC, Antwerp, 1978, © Christina Kubisch; Christina Kubisch and Fabrizio Plessi, Liquid Piece (with Fabrizio Plessi as gurgler), ICC, Antwerp, 1978, © Christina Kubisch and Fabrizio Plessi

These performances build upon a new style of listening, based on the viewer’s mobility. As Christina Kubisch explained in an interview,[9] the idea is to enable the viewer to switch from the live performance to a performance seen through the filter of new technologies. Reality is altered once it is transposed with the help of the video device. All the positions held by the viewer give them a different way of hearing and seeing things. In addition to this, the continuity of the musical composition’s repetitive structure facilitates the viewer’s movements and changes of perspective. The visitor becomes an experimenter.

In her early work, Kubisch had already given a great deal of importance to the position of her audience, prompting them to distance themselves through provocative and ironic techniques. With the “video concert,” the viewers’ commitment is developed even further because their circulation in the exhibition space is the key to appreciating the artistic experience they are being offered. But this exchange of roles between the viewer and the experimenter will come to a climax in the Electrical Walks that the artist has been working on since 2004. Here, the idea is to stroll around public areas equipped with wireless helmets specially designed by the artist, which translate and make it possible to hear electromagnetic fields all around us. During the course of these walks, the individual can choose his own pace. The artist only intervenes as a guide, orienting the general trajectory of the experience.

[1] Stille Nacht is perhaps the only performance during which traditional flute sounds are produced.

[2] Audio recording available on “Musik und Gender im Internet”: https://mugi.hfmt-hamburg.de/Kubisch/ (accessed May 9, 2017).

[3] Ingmar Lähnemann, “Public Piece. The Performative Aspect in Christina Kubisch’s oeuvre,” Christina Kubisch. Electrical Drawings, Works 1974–2008, Wulf Herzogenrath and Ingmar Lähnemann, eds., Heidelberg: Kehrer Verlag, 2008, 13.

[4] See interview with Christina Kubisch by Lou Jonas, March, 2016, section Interviews on this website.

[5] Audio recording available on “Musik und Gender im Internet”: https://mugi.hfmt-hamburg.de/Kubisch/ (accessed May 9, 2017).

[6] The nuance is voluntary because, on the recording of the performance, a seemingly electronic pulse resounds at regular intervals.

[7] This instrument was already associated with the water jet in Two and Two (1976–77) to signify the element “water.”

[8] It is worth adding that these changes are probably part of the listening experience for the viewer, whose attention is partly responsible for the associations made between sound and meaning.

[9] See interview with Christina Kubisch by Lou Jonas, March, 2016, section Interviews on this website.