Lori Zippay on

Willie Boy Walker

Willie Boy Walker, the self-proclaimed “first video disc jockey,” created a series of satirical video works in the 1970s that adopted the forms and genres of popular television as media and cultural critique. Deploying humor and parody, Walker crafted a distinctive fusion of comical sketches, narrative TV formats, and fictional characters, at once subverting and embracing television conventions. Although his early video works, including The Weekend Tapes (1971–74) and Prurient Interest (1974), were featured in a solo screening program at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1976 and at Dokumenta 6 in 1977, among other high-profile exhibitions, and were honored at the 1975 San Francisco Film Festival, Walker remains a relatively unknown figure in video art history. Following his formative years in the 1970s Bay Area performance and video art scene, Walker went on to act in, write, and direct independent feature films.

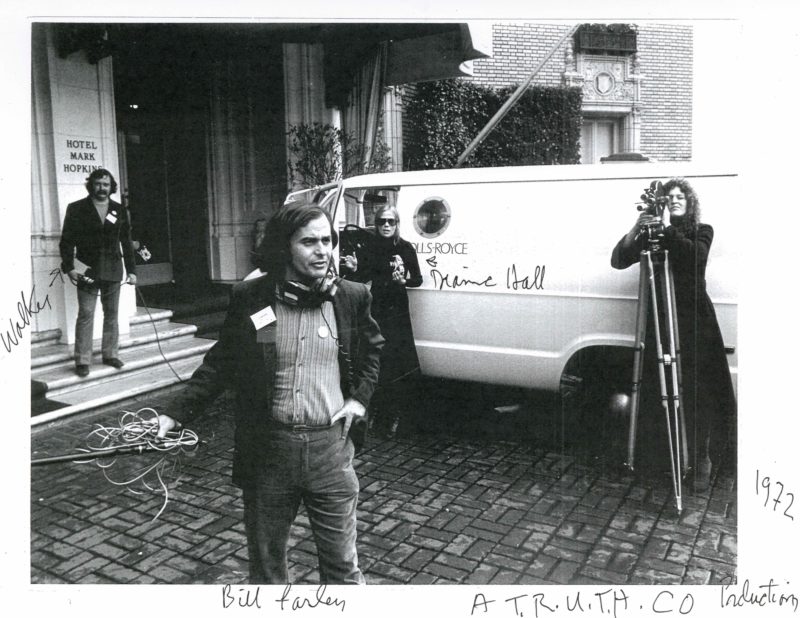

Willie Boy Walker (left) with William Farley (front) and Diane Hall (back) shooting a performance piece that took place at the Mark Hopkins Hotel, San Francisco, 1972, © Willie Boy Walker

Born in 1945 in New Jersey, Walker was a first-wave baby boomer, a cohort that was the first generation of Americans to have grown up with television as a mass cultural force. Video art of the early 1970s is often defined by its complex relationship to television, assuming an oppositional or critical position in relation to the mass media and the television industry. Indeed, many of the tropes of early video art—extended duration, “real time,” in-camera edits—are not only by-products of the parameters of early video technology, but are also deliberate counterstrategies and responses to commercial television’s pace, form, and content. Many “first generation” artists embraced video’s potential for intervention, an emergent medium through which to “talk back” to the mass media and dominant culture.

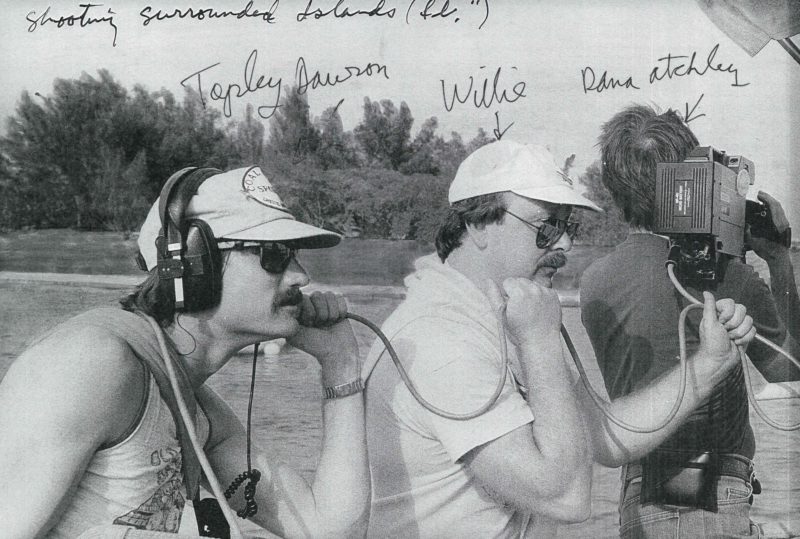

Willie Boy Walker (center) with Tapley Dawson (left) and Dana Atchley (right) shooting Surrounded Islands, Florida, © Willie Boy Walker

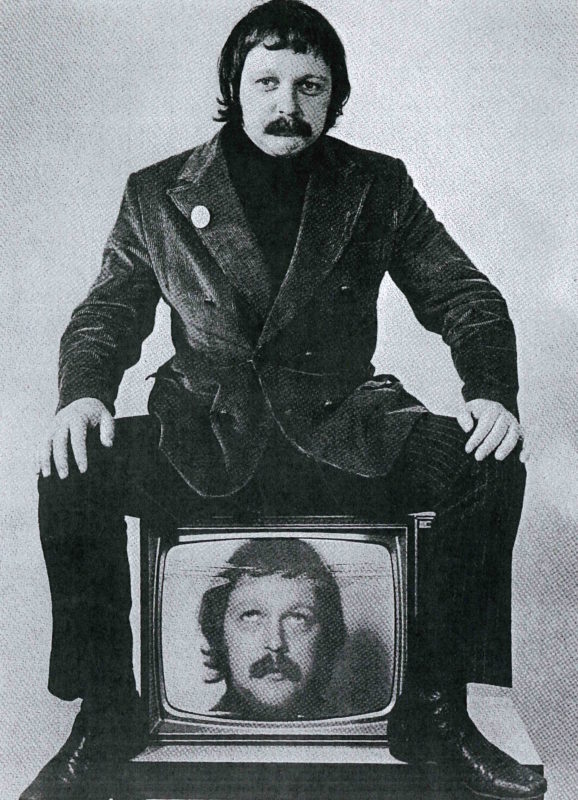

Artists such as Walker, who appropriated and then subverted the popular formats, genres, and conventions of television as an artistic and conceptual strategy, further complicated this relationship. Although such re-creations and interventions into television forms became an important theme of video art in the late 1970s and 80s, Walker’s early works are prescient in their humorous, self-reflexive adaptations of TV culture. Walker created parodic television commercials and sketches, which he populated with comic characters such as “Captain Video” (a figure, played by Walker himself, who climbed out of the TV to interact with the viewer), the “Long Ranger,” and Father Guido Sarducci (played by Don Novello), who became known in the late 1970s and 80s for his recurring role on the popular network television show Saturday Night Live.

Writing in 1976, Walker termed himself “a collector of video oddity, Art and Humor or anything you wouldn’t see on everyday television.”[1] In the early 1970s, Walker, who lived in Oakland, California, hosted regular two-hour performance/video art shows that he titled “The World of Willie Boy Walker and His Friends.” These informal events were, according to Walker, “performed on the week-ends by various artists and friends. The accepted videotapes would be edited and assembled into a show or collection of oddities to be shown to peers or interested parties.”[2] Walker recently described the events in more detail in an interview:

In the 70s there was a wonderful group of people interested in making videos … in homes, studio lofts—creating video shows, getting equipment, sharing equipment …These are video artists, filmmakers, music composers, actors, photographers, performance people, people who wanted to capture and save and share, in order to make things …We had a TV slumber party. Everyone brought a videotape to show, and we watched all night and had a sleepover, too. We even had outdoor presentations in parks or camping or backyards—food and drink, friends … ‘Show & Tell TV”… [3]

Willie Boy Walker, graduation picture of MFA students at the California College of Arts and Crafts, now known as the California College of Arts, 1971–72, photo: Robert Arnold, © Willie Boy Walker

Like these hybrid events, Walker’s video works are improvisational, performance-driven, narrative assemblages that are filtered through a countercultural lens that was unmistakably of its time and place.

The San Francisco Bay Area of the late 1960s and early 70s was an important and influential locus for the emergent West Coast performance and video art scene. The rich and eclectic history of Bay Area video art is rooted in the alternative art and cultural movements that emerged with the social and political transformations of the era. Interdisciplinary collectives such as Ant Farm (who created their iconic Media Burn in 1975), Video Free America, and Optic Nerve used the nascent video technology to explore the meaning and impact of media images, in works that reflected a collaborative, even communal sensibility, often laced with irreverent humor. Bay Area conceptual artists, such as Howard Fried, Paul Kos, and Terry Fox, among others, were among the foundational figures of performance-based video art in the United States. The National Center for Experiments in Television (NCET) at KQED-TV, the San Francisco public television station, was a generative force for artists’ investigations into new electronic imaging languages. Such was the fertile, countercultural environment in which Walker and his fellow Bay Area artists created and presented their video “oddities.”

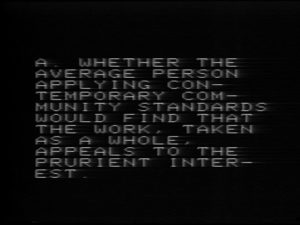

Prurient Interest, 1974, script by Larry Arnstein, produced and directed by Willie Boy Walker, video stills © Willie Boy Walker, Larry Arnstein

Produced at the Center for Contemporary Video Arts at California College of Arts & Crafts, Walker’s 1974 Prurient Interest is a low-tech, free-form narrative that poses a satirical view of censorship in the media entertainment industry, which was the subject of a heated cultural debate in the United States at the time. Several high-profile cases involving the censorship and banning of movies for violating local or state obscenity laws had exposed a cultural divide around definitions of pornography and sexual content in popular entertainment. In 1974, in a landmark decision (Miller v. California), the US Supreme Court redefined the legal standard for obscenity. Walker brings an absurdist yet pointed critique to this highly politicized argument, opening Prurient Interest with quotes from Chief Justice Warren Berger’s guidelines for determining obscenity: “Whether the average person, applying contemporary community standards, would find that the work, taken as a whole, appeals to the prurient interest … or describes in a patently offensive way sexual conduct …” [or that the work] “lacks serious literary, artistic, political or scientific value.”

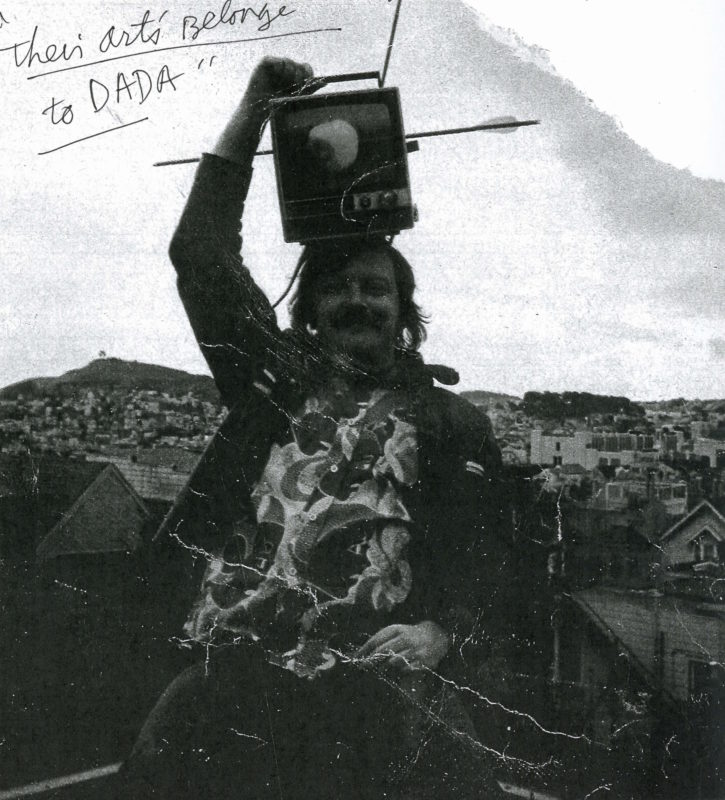

Willie Boy Walker, Homage to William Tell, from an article in Esquire Magazine called “Their Hearts Belong to Dada,” 1980s, © Willie Boy Walker

The description of Prurient Interest in the 1978 video catalogue of Electronic Arts Intermix (EAI), the New York–based media arts organization, outlines the work’s sardonic premise: “A video play revolving around a movie producer’s jousting with the Board of Censors. Week by week he comes closer and closer to approval, culminating in the battle over his feature ‘Eat Me in St. Louis.’” Unfolding with deadpan, improvisational humor, Prurient Interest follows members of a popcorn-and-pizza-eating local community standards board in New Jersey as they watch and discuss the merits and content of the film. (“Eat Me in St. Louis”—a pun on the classic Hollywood musical “Meet Me in St. Louis”—is never seen; Walker reveals the movie only through its exaggeratedly “sexy” and overwrought soundtrack.) Although the censors react with obvious titillation to repeated screenings of the “dirty movie,” they ultimately reject it as “unsuitable for viewing.”

Many of the individuals who contributed to Prurient Interest (including actor/comedians David Hurwitz and Don Novello, and writer Larry Arnstein) had been associated with the Chicken Little Comedy Show, a live, “drop in” comedy hour that aired on the San Francisco UHF television station KEMO-TV in 1972. The Chicken Little show featured satirical sketches that lampooned the mass media—TV, movies, advertising—with irreverent humor, functioning as an alternative or “underground” television comedy. Many Chicken Little alumni went on to high-profile careers in American satirical entertainment (The Groove Tube, Not Necessarily the News, Saturday Night Live), engendering a comic sensibility that influenced generations and continues to be felt in popular culture.

Viewed from a distance of some forty-five years, Walker’s video works of the 1970s can be seen as an integral part of the creative mix of the experimental Bay Area performance/ video art scene, yet they also stand out as distinctive. Walker’s use of the short “sketch” format and fictional characters reveals a movement towards narrative structure and storytelling that was relatively rare in video art of the mid-1970s. (Notable exceptions include Eleanor Antin’s fictional narratives of this period, in which she explores role-playing and representation, and William Wegman’s comedic conceptual performances, which often take narrative form.) In 1978, Walker’s Troubled Zone, a tale of a Hollywood starlet and a robot that comically evoked the iconic TV show The Twilight Zone, was screened at the Whitney Museum of American Art in the program “Short Narrative Video,” which also included works by Mitchell Kriegman, Jane Brettschneider, and David Lamelas.

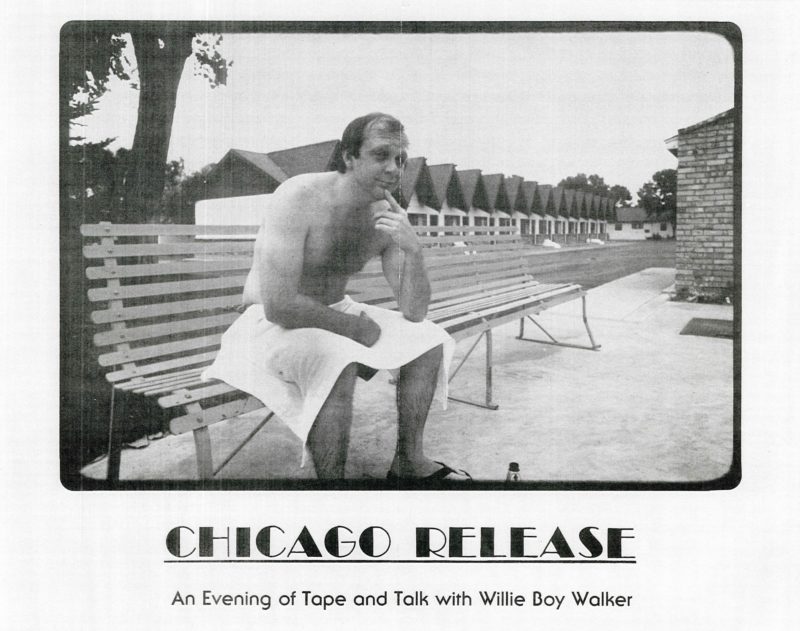

Invitation to/announcement of Chicago Release. An Evening of Tape and Talk with Willie Boy Walker, © Willie Boy Walker

Walker, who acknowledges the influence of the experimental TV pioneer Ernie Kovacs, states that producing his video works “was more like putting on a play. It was wires and strings, smoke and mirrors. Those were the times. We’d work with anybody who had equipment and space, wherever we could go. It was all about humor and satire and parody.”[4] Even as they satirize and adapt the forms and conventions of television and the Hollywood movie industry, Walker’s narrative video works, including Prurient Interest, can be seen to presage the artist’s transition to feature films at the beginning of the 1980s. Fusing political and cultural critique with comedy, popular genre parodies, and quirky fictional characters, Walker’s rarely seen early works of the 1970s are prescient examples of video art’s interactive and often synergistic engagement with and influence on mass media entertainment.

[1] Willie Boy Walker, The World of Willie Walker (program notes), Whitney Museum of American Art, The American Filmmaker Series, June 1976.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Interview between Willie Boy Walker and Anna Sophia Schultz, August 2017, published on this website.

[4] Willie Boy Walker, in phone conversation with the author, July 7, 2017. I would like to thank Anna Sophia Schultz, Researcher & Curator of the Research Project “Video Archive” at the Ludwig Forum für Internationale Kunst, for her extensive research and efforts in facilitating contact with Willie Boy Walker.