Maria Engelskirchen on

Jonathan Borofsky

Standing on a meadow in front of a mountain backdrop are two high posts, connected by a taut rope, with a dog balancing between them, while overhead clouds drift by. After a couple of steps the dog folds in its forelegs and appears to get ready to kowtow, but immediately leaves this position again and retreats, transfers its weight onto its hind legs and begins to perform the very same sequence of movements again. The animal is haloed by a sparking yellow nimbus—an indication that the rope is possibly electrically charged, although this seems to have no detrimental effect on the dog’s acrobatic skills. The animated video loop is identifiable as a work by the American artist Jonathan Borofsky (b. 1942 in Boston, MA) thanks to the eye-catching sequence of seven numbers positioned in the center of the lower section. As if keeping track of how many frame settings make up the animated sequence, the numbers run from 2,671,428 through to 2,671,481 synchronously with the movements of the dog on the rope, back and forth.

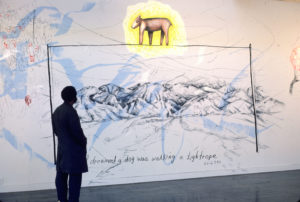

Jonathan Borofsky, I Dreamed a Dog Was Walking a Tightrope, wall painting in the installation All ls One, Portland Center for the Visual Arts, 1979, © Jonathan Borofsky

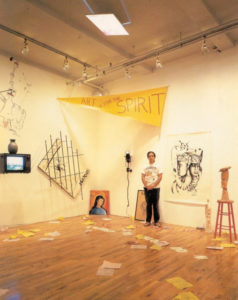

Continuous counting has been an integral part of Borofsky’s artistic practice since 1969. The decision he made at that time—to forgo the production of images and the writing down of thoughts, which he had diligently followed in the preceding years—and instead focus his attention on the pure notation of natural numbers, is in its approach as conceptual as the activity is disciplining and meditative.[1] It was not until 1972 that Borofsky again created figurative drawings in parallel to the numbering, which he signed with the respective current number of his counting sequence[2], thus ordering them into his personal chronology.[3] While the number sequence carried forward the sober concept, his drawings frequently took up personal and spiritual themes. Noting how Borofsky was constantly relating his artistic creativity back to his identity and inner emotional life, the art historian Richard Armstrong was moved to describe these works as “self-revelatory art.”[4] Borofsky’s recordings of dreams, mostly comprising sketch-like drawings and concise short descriptions, were also part of this approach. The work in the video archive of the Ludwig Forum in Aachen is based on one such drawing, completed before 1979 and titled I dreamed a dog was walking a tightrope.[5] Before Borofsky turned the motif into the starting point for a short animation in 1980, it had already featured as a wall drawing in his installations in various exhibitions.[6] Ever since his first solo exhibition at the Paula Cooper Gallery in New York in 1975, Borofsky had liberated his drawings from the intimacy of his notebooks and presented them on gallery walls in large format. Here he used overhead projectors, which allowed him to scale the drawings and then retrace them.[7] His installation works not only extended over the walls but also the floor and ceiling, and they were closely entwined with the position of the viewer, because the lines in the exhibition space were in part arranged such that they—like an anamorphosis—only yielded an image when viewed from a specific perspective.[8] Borofsky’s videos, including Tightrope, could also be seen amidst the wall drawings and objects in the exhibition space, on television sets positioned at the viewer’s eye level and without any seating provided,. Without any separation from the other pieces, the short repetitive animation sequences remained closely tied to the dominating medium in Borofsky’s exhibitions, namely the drawing.[9] The interdependence between exhibition space and drawing, which manifests itself in how the drawing detaches from the sheet as its pictorial medium and emphasizes the processuality, demands a greater involvement by the viewer, an aspect that the curator Bernice Rose discerned in 1976 in a text on the exhibition Drawing Now at the Museum of Modern Art in New York: “The drawing is seen as a field coextensive with real space, no longer subject to the illusion of an object marked off from the rest of the world. The space of illusionism changes, merges with the space of the world, but by doing so it loses its objective, conventional character and becomes subjective, accessible only to the individual’s raw perception.”[10]

Jonathan Borofsky, I Dreamed a Dog Was Walking a Tightrope, wall painting in the installation All ls One, Portland Center for the Visual Arts, 1979, © Jonathan Borofsky

In this spirit, artists like Agnes Martin, Eva Hesse, Sol LeWitt, and Robert Rauschenberg had experimented since the 1960s with the autonomy of the medium, which no longer remained an exploratory tool, merely the sketched precursor to a work still to be completed. At the same time, the emancipation took place in a reciprocal exchange with other art forms, with Eva Hesse for example “mixing the processes of drawing and sculpting.”[11] Borofsky’s interest in animated film can thus also be located within the diversification of contemporary drawing practices in the United States. In contrast to his drawings, installations, and monumental sculptures in public space,[12] outside of inventory catalogues his video works have hitherto attracted little attention.[13] Although relatively small in number, they represent an undoubtedly notable part of his extensive oeuvre, not least because Borofsky taught at the California Institute of the Arts between 1977 and 1980, alongside fellow-artists like John Baldessari and William Wegman, and was thus connected with one of the liveliest contemporary experimental video art scenes.[14] In the 1970s, two programs were founded at the Institute: Experimental Animation and Character Animation.[15] But courses on Animation Production Techniques were also offered at the School of Visual Arts in New York, where Borofsky had been a teacher immediately prior, from 1969 to 1977, attended for example by the painter Maria Lassnig before she created her animated films.[16]

Jonathan Borofsky, I Dreamed a Dog Was Walking a Tightrope, wall painting in the installation All ls One, Portland Center for the Visual Arts, 1979, © Jonathan Borofsky; Jonathan Borofsky, I Dreamed a Dog Was Walking a Tightrope (1980), video in the exhibition Jonathan Borofsky, Paula Cooper Gallery, 155 Wooster Street, New York City, October 18 – November 15, 1980, © Jonathan Borofsky

Borofsky’s first animated film was made in California, however, for which he cooperated in part with the artist Megan Williams. She completed the animation for the video Man in Space (1982–83) following Borofsky’s directions. For I dreamed a dog was walking a tightrope, he undertook the animation himself and specifically sought to create a dilettantish and somewhat clumsy composition, so that the movements of the dog and clouds almost seem staccato-like.[17] Other video works created with advanced technologies like rotoscoping show that the artist delved into a variety of animation methods and thus possessed some expertise.[18] In a review of the first large Borofsky retrospective, the art critic and media artist Christine Tamblyn accordingly described the Tightrope video as a “crudely rendered drawing of a dog running across a tightrope using sophisticated computer-generated video technology.”[19] The intentionally primitive drawings, the workmanship of which the art theorist Lucy Lippard has characterized as “churlishly childish,”[20] correspond to the desire for a direct transposition of thoughts from the mind onto paper, and in their systematic regression radiate a naivety that distinguishes Borofsky’s dream drawings from the decidedly sexualized dream analyses of the Surrealists.[21] Borofsky’s concern is instead to activate collective emotions in viewers. He draws on his own experiences and deduces more general human desires from them.[22] Precisely in the nonverbal, purely visual confrontation, his drawings and videos converge with a quality of animated films that Jayne Pilling has characterized as “animation’s unlimited potential as a medium for communication”:[23] “The animated short film can provide, quite literally, a blank page on which to draw forth an imaginative vision which can communicate, and can do so also without words. Transcending the boundaries of language can also give voice to that which is hard to articulate, because so bound up with unconscious feelings […].”[24]

Jonathan Borofsky, I Dreamed a Dog Was Walking a Tightrope (1980), video in the exhibition Jonathan Borofsky, Paula Cooper Gallery, 155 Wooster Street, New York City, October 18 – November 15, 1980, © Jonathan Borofsky

While Borofsky was seen as a representative of Neo-Expressionism in the 1980s, his explicitly personal, spiritual subjects represented the breaching of a taboo,[25] causing him to retrospectively assume a unique position in the American art scene of the 1970s and 80s. In their continuation of these enigmatic themes, already deliberated on in the medium of drawing, and their refusal to indulge in crafted virtuosity, his videos contribute decisively to this perception. To contextualize them against the backdrop of the contemporary development of (artistic) animated film would extend the reception of Borofsky’s work, hitherto centered primarily on the subject matter, by adding a historical dimension, namely that of media technology and institutional settings.

[1] Cf. Lucy Lippard, “Jonathan Borofsky at 2,096,974,” Artforum, vol. 13, no. 3 (Nov. 1974), 63–64, here 64.

[2] Cf. Richard Marshall, Jonathan Borofsky’s Installations. All is One, exh. cat. Stockholm 1984, 87–104, here 90.

[3] Pierre Bourdieu has pointed out the fictive dimension of the biographical chronology as a linear narrative of a life story: “L’illusion biographique,” Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales, 62–63 (June 1986), 69–72.

[4] Richard Armstrong, “Comparing Notes with Jon Borofsky,” exh. cat. Jonathan Borofsky, Moderna Museet, Stockholm, September 8 to October 21, 1984, Uddevalla, 1984, 109–117, here 109.

[5] A reproduction is to be found in the exh. cat. Jonathan Borofsky. Dreams 1973–81, Kunsthalle Basel, July 12 to September 13, 1981, Institute of Contemporary Arts, London, October 9 to November15, 1981, London, 1981.

[6] The drawing was shown for example at the Portland Center for the Visual Arts, Portland, Oregon, 1979.

[7] Borofsky is said to have gotten the idea to draw directly onto the walls from Sol LeWitt. Cf. Michael Austing in mus. cat. Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth. 110, ed. Michael Auping, London, 2002, 219.

[8] One example is his Self-Portrait with Big Ears (Learning to Be Free) in the exhibition Westkunst. Exh. cat. Westkunst. Zeitgenössische Kunst seit 1939, Rheinhallen, Cologne, May 30 to August 16, 1981, Cologne, 1981.

[9] Referring to the animated films of William Kentridge, Rosalind Krauss has spoken of how his interest in the medium of film arose out of the processuality of the “graphic medium”: “[A]nimation here—the run-on projection of the frames recording successive phases of the drawing which thereby generates the sense of a single work in motion—is a kind of derivative of drawing.” Rosalind Krauss, “‘The Rock.’ William Kentridge’s Drawings for Projection,” October 92 (Spring 2000), 3–35, here 9. Due to the ongoing succession of numbers in the Tightrope video, a similar interest is identifiable in Borofsky’s work, stemming from drawing rather than video.

[10] Bernice Rose (ed.), exh. cat. Drawing Now, January 23 to March 1, 1976, Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1976, 14.

[11] Catherine de Zegher, “Die Befreiung der Linie. Zeichnung und Subjektivität vom 20. Jahrhundert bis in die Gegenwart,” Räume der Zeichnung, eds. Angela Lammert, Carolin Meister, and Jan-Philipp Frühsorge, Nuremberg, 2007, 189–211, here 199.

[12] With Ballerina Clown (1990), which Peter and Irene Ludwig bestowed on the newly founded institution in 1991, the Ludwig Forum in Aachen also possesses a sculptural work by Borofsky.

[13] Cf. Michael Rush, “Jonathan Borofsky. Man in Space. 1982–1983,” mus. cat. Collection Nouveaux Médias Installations. La collection du Centre Pompidou Musée national d’art moderne, Paris 2006, 102–103.

[14] Cf. Gregory Battcock (ed.), New Artists Video. A Critical Anthology, New York 1978. See also exh. cat. Reel Work. Artists’ Film and Video of the 1970s, Museum of Contemporary Art, Miami, February 24 to May 2, 1996, Miami, 1996.

[15] Cf. Maureen Furniss, Animation. The Global History, London, 2017, 318.

[16] Cf. Manuela Ammer, “‘Be aware, be aware, be aware.’ Obacht vor Maria Lassnigs Filmen,” Parkett 85 (2009), 102–109. On Maria Lassnig’s time in New York and her drawings created there while exploring the new visual media, see Barbara Reisinger, “Drawing, Bodies, Television. Maria Lassnig and the 1970s in New York,” exh. cat. Maria Lassnig. Dialogues, Albertina, Vienna, May 5 to August 27, 2017, Kunstmuseum Basel, May 12 to August 26, 2018, Munich, 2017, 37–47.

[17] Cf. Jonathan Borofsky, exh. cat. Philadelphia Museum of Art, October 7 to December 2, 1984, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, December 20, 1984 to March 10, 1985, University Art Museum, Berkeley, April 7 to June 16, 1985, Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, September 13 to November 3, 1985, The Corcoran Gallery of Art, Wash., D.C., December 14, 1985 to February 9, 1986, Philadelphia, 1984, 179.

[18] The animation of Borofsky’s video work Giraffe/Escalator (1988–95), shown in the exhibition curated by Bernice Rose, Allegories of Modernism. Contemporary Drawing (February 16 to May 5, 1992, MoMA), was created using rotoscope. (The exhibition checklist is accessible online at: https://www.moma.org/documents/moma_catalogue_360_300064453.pdf [accessed September 4, 2017]).

[19] Christine Tamblyn, “Manifestations of Thought. The Borofsky Exhibition,” The UC Berkeley Graduate Assembly Newsletter, August 1985, 1. Christine Tamblyn papers, MS-F11 Special Collections and Archives, The UC Irvine Libraries, Irvine, California [accessed August 30, 2017].

[20] Lippard 1974, 64.

[21] Cf. Armstrong 1984, 113.

[22] In a conversation with Udo Kittelmann, Borofsky says: “So I get very specific with my art and try to discuss human issues either through my dreams or through political statements or humanistic statements, because it’s the best I can do. […] I start with myself and put out into the world my own lessons, my own search for freedom.” Udo Kittelmann, “Jonathan Borofsky and Udo Kittelmann. A Conversation,” idem. (ed.): Jonathan Borofsky. Dem Publikum gewidmet, Ostfildern bei Stuttgart 1993, 82–95, here 86.

[23] Jayne Pilling, “Introduction,” idem. (ed.): Women and Animation. A Compendium, London, 1992, 5–7, here 5.

[24] Pilling 1992, 6.

[25] Cf. Lippard 1974, 64.