Sophie Goltz on

Wolf Vostell

“Video is an independent medium that shares with comparable media such as film and television above all the reproduction of continuous recordings of images. Electronics have enabled expanded technical possibilities: image distortion, multiplication, reversal, color change, dissolution.”[1]

Wolf Vostell, who was born in 1932 in Leverkusen and died in 1998 in Berlin, was a co-founder of European happening art and a decisive contributor to the Fluxus movement. He was—alongside Nam June Paik—one of the first international video artists. Vostell came to prominence in the 1950s through his De-coll/age actions, which were later followed by De-coll/age videos, magnetically distorted television images with the hypnotic sound of an alarm. His use of television images was novel amidst the surge of criticism of the media to be found in the art of the 1960s.

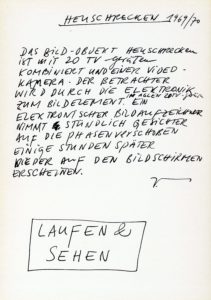

Invitation to/announcement of the exhibition Wolf Vostell – Elektronisch at the Neue Galerie im Alten Kurhaus, 1970, Archive of the Ludwig Forum für Internationale Kunst, Aachen; Wolf Vostell, script for Heuschrecken, 1969/70, © The Wolf Vostell Estate, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn; Invitation to/announcement of the exhibition Wolf Vostell, Kunstreisen. Fluxus-Zug at the Neue Galerie – Sammlung Ludwig, 1981, Archive of the Ludwig Forum für Internationale Kunst, Aachen

Vostell’s oeuvre alternates between a pioneering spirit, ingenious innovation, self-historicization, and messianic self-stylization. His ongoing performance as the “eternal Jew,” which along with payots and a kippah-like fur cap went hand in hand with changing his name, stylized the artistic individual Vostell into a kind of anti-establishment icon of his age. Vostell dared to undertake his own analysis and set his own trends, following the zeitgeist and its artistic gesture à la Joseph Beuys or Bazon Brock; together they formed an artistic elite dedicated to asserting an extended concept of art.

Television recordings/reports on the opening of the Vostell train in Aachen (Journal 3, Aspekte) and shots of the opening party held in the Neue Galerie Sammlung Ludwig, Aachen, 1981, video stills © The Wolf Vostell Estate, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

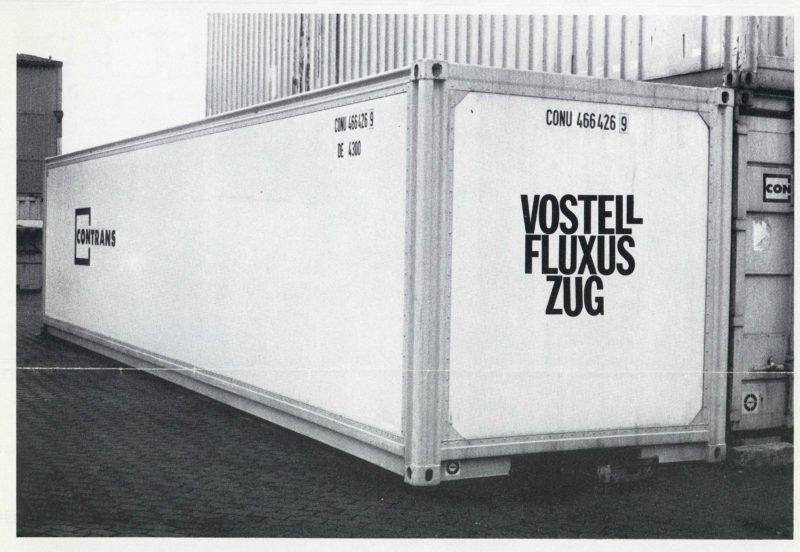

Along with the recently digitized video works T.O.T. (1974) and TV-Butterfly (1980), the collection of the Ludwig Forum Aachen also holds recordings made of programs shown on West German television: a live discussion on the Fluxus Train (which stopped at different cities in NRW from May 1 to September 29, 1981; in Aachen from May 8 to 12, on platform 9) and of the culture programs Aspekte and Journal 3. The latter was first broadcast on May 8, 1981, the day on which liberation from German fascism is remembered.

Wolf Vostell, coach of his Fluxus train, 1981, © The Wolf Vostell Estate, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Time and again, Vostell engaged with this legacy in his work, translating society’s crisis situations, caused by war and tyranny, along with falsifications of and the forgetting of history, into a New Realism. He sought to harness art as a means for countering the break with civilization. Modernity was seen as culminating in and thus having an enlightening impact on society. During the live discussion on the Fluxus Train (1981), Vostell described his career as starting with the student movement of 1968, with which art changed as a medium of criticism. The time of political indignation—whether triggered by social analysis, ecologically minded criticism, or environmental awareness—had ended in disappointment, and the effectiveness of analytical criticism had been called into question. The New Realism was now joined by the imagination, the power of fantasy also used as a metaphor to draw a distinction from the banality of the individual. Politics had according to Vostell ultimately dissolved into the everyday vocabulary of the media’s sensory overload.[2] He opposed the voiding of social issues, characteristic of the time, with the Fluxus train, a rolling museum of life, while his interest was captured by reappraising the processes of life that go unrecognized and seeing them as art processes. As the video clearly shows, Vostell has exposed himself to his public; at that always found the Ruhr miner to be more sympathetic than the region’s bourgeois art club member.

Wolf Vostell in coach no. 7 of his Fluxus train visiting the Aachen-based group Blaustich, 1981, photo: Wolfgang Plitzner, © The Wolf Vostell Estate, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn; Invitation to/announcement of the exhibition Wolf Vostell, Kunstreisen. Fluxus-Zug at the Neue Galerie – Sammlung Ludwig, 1981, Archive of the Ludwig Forum für Internationale Kunst, Aachen

In the spirit of the times, he defended the possibility of communicating about art and thus entering into a dialogue on art. Well into the 1980s, he followed an idea of communicating art that had its beginnings in Bazon Brock’s visitor school[3] at the documenta 5 (Kassel, 1972): a radical re-education of sensibilities towards contemporary art by annulling the old patterns of perception. In 1987, when his controversial concrete sculpture 2 Beton-Cadillacs in Form der nackten Maja (2 concrete cadillacs in the form of the nude maja) was erected as part of West Berlin’s Skulpturenboulevard (Sculpture boulevard),[4] he pursued similar arguments when speaking about his art. In both Berlin and Aachen, his complex arguments were directed at man’s transformation of nature and the environment.

TV-Butterfly, 1980, video stills © The Wolf Vostell Estate, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

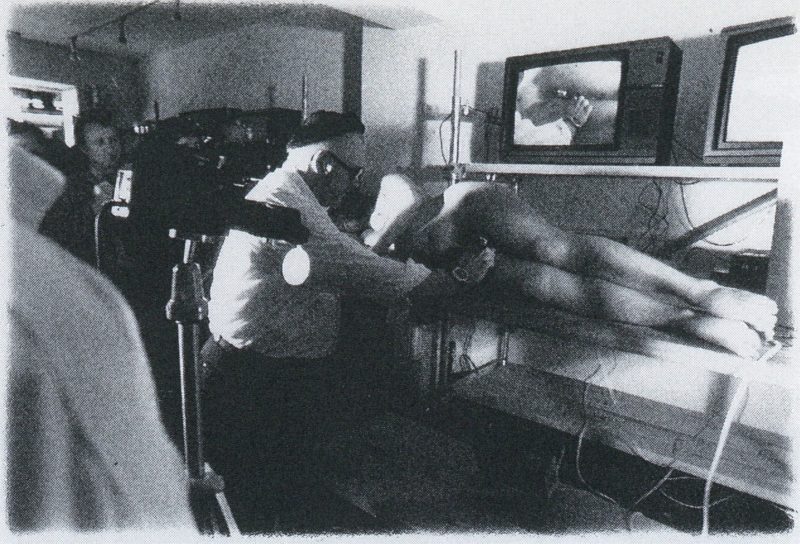

Vostell also addressed the construed opposition between culture and nature in the video TV-Butterfly (1980, 45 min. color, sound). A mini control monitor nestles in a hairy vulva, the thighs firmly pressed together. Recalling Gustave Courbet’s painting L’Origine du monde (1866), this pictorial motif in a diverse array of variations had assumed a key place in Vostell’s works since the 1970s. Always relating to the origin, the vulva in Vostell’s first longer film, Desastres (1972), is confronted with concrete. The delicacy of the genitals is brutally cut through.

Wolf Vostell producing TV-Butterfly, 1980, photo: Angelika Wengler, © The Wolf Vostell Estate

Vostell also reflects on the relationship between man-nature-culture in the work TV-Butterfly. While the images alternate on the monitor, a woman’s voice chimes in, singing in an unchanging chord “ever forever.” A hand with pink-varnished fingernails materializes and then vanishes again. Cut. Butterflies on arrangements of blossoms embody unfettered nature. They alternate with the vulva. The frequency of the images increases, a pendulum light swings over the technoid nude. The camera changes zoom. In the mini control monitor the same motif is recognizable as in the large camera shot; a doubling takes place. The rapid cuts hystericize the image sequence and the transition between the motifs, which increasingly slip out of camera focus and become fuzzy. Moreover, the sound changes, but the voice remains the same. The final shot is an abstract image of human skin.

Vostell’s experimental films do not follow a narrative thread; often they draw on vividly alive motifs like that of a naked female body as a way of focusing on the relationship between this body and materiality, either that of the appropriated surroundings or the information age. Popping up again and again are images evoking the tyranny of German fascism. With his film collages and his courage to experiment both in terms of content and technology with the medium of film/video, Vostell adopted an avant-garde position early on, one that also correlates to his actions, happenings, and performances. He himself characterized his films as “psychological units of experience” in which delays, repetitions, and distortions are analogous to what is happening in society.[5]

T.O.T., 1973, video stills © The Wolf Vostell Estate, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Produced by the Video-Forum of the Neuer Berliner Kunstverein, T.O.T. (Technological Oak Tree, 1973, 40:31 min, black-and-white, sound) is an artistic action in three acts. The shot giving the video its title is of a large, fully grown oak tree, an ampere meter montaged on the frame, the needle pointing at 0 mA. The still stands for 50 seconds between T.O.T. act 2 and act 3. Each of the acts is preceded by directions: “Hold your hand over the water for 15 minutes” (action 1), “Move your foot around in syrup for 15 minutes” (action 2), “Squash bread between your legs for 15 minutes.” Each of the directions is performed by a naked female body. The camera begins with the face in every act—in acts 2 and 3 she looks directly into the camera—before focusing on the relevant part of the body. The camera is accompanied by an artificial mechanical sound that recalls Vostell’s Fluxus concerts. Tactfully deployed in the background at the beginning, by the last act it has moved into the foreground.

In the first act, with the hand touching the water surface, the hand suspended over the water is encircled in a 180-degree panning shot until the image dissolves into the detail, the finger. In the second act, the camera brushes the painted toenails before it focuses on the whole foot, over which syrup flows, haltingly at first, then ever thicker, until the sole is completely immersed in the sticky fluid. The foot plays with the syrup, as slowly the camera zooms in at the toes and heel . In the third act, a slice of white bread is pressed between the women’s thighs close to the vulva. The muscle contraction in her thighs is barely visible, the camera focusing more on the crust of the slice. The motif loses its clear contours and stylistically comes to resemble the surface of a dildo, a suggestive heterosexual charging.[6]

As co-founder, with Wolf Kahlen and others, of the first Videothek (video library) in Germany and Europe, in 1972 at the Neuer Berliner Kunstverein and thus in the early phase of video art, Vostell was already showing an interest in the direct presentation of the medium to the public as well as in the production conditions. Set up to also serve as a production location—film equipment was not particularly cheap—the library launched a video art collection in parallel. Together with other West Berlin avant-garde artists, the DAAD (German Academic Exchange Service), and the Neuer Berliner Kunstverein, Vostell organized the Aktionen der Avantgarde I (ADA 1, 1973)[7] and Aktionen der Avantgarde II (ADA 2, 1975).[8] DAAD grant holders living in West Berlin at the time, for instance Robert Filliou, Mario Merz, Taka Iimura, and Allan Kaprow, were invited to take part. West Berlin was consumed by the avant-garde fever of contemporary art currents like performance, intervention, and action; the video documentations of this activity are today an integral part of the collection.

Wolf Vostell is considered one of the founding fathers of video art in Germany. Beginning with the technical distortions of images from mass communication media like television, he soon developed a distinctive and contemporary artistic practice employing video technology. In the 1970s, Vostell was actively involved with the Latin American art scene, while he joined the struggle against the dictatorships in Argentina and Chile. Together with the CAYC group in Buenos Aries, he organized an international open letter of protest against General Augusto Pinochet that was co-signed by a number of other German artists, including Joseph Beuys and K.H. Hödicke. Down to the present day his video work is considered to have set the tone stylistically there for a whole generation of artists.

[1] Video-Forum des NBK, published by the Neuer Berliner Kunstverein, inventory catalogue, Berlin 2001, quoted from Dieter Daniels, “ Video Art. Yesterday, Today, Tomorrow? Continuity and Discontinuity from 1970 until Today,” Marius Babias, Kathrin Becker, Sophie Goltz, Time Pieces. Video Art since 1963, Cologne, Walther König, 2011, 96.

[2] Cf. Wolf Vostell, audience discussion, May 11, 1981, video archive of the Ludwig Forum.

[3] Roland Nachtigäller, Karin Stengel, Friedhelm Scharf (eds.), Wiedervorlage d5 — Eine Befragung zur documenta 1972, exh.cat. documenta Archiv, Ostfildern, Hatje Cantz, 2001. See also: Bazon Brock, Ästhetik der Vermittlung. Arbeitsbiographie eines Generalisten, ed. Karla Fohrbeck, DuMont, Cologne, 1977.

[4] Cf. Marius Babias, Kathrin Becker, Sophie Goltz (eds.), Kunst und Öffentlichkeit. 40 Jahre Neuer Berliner Kunstverein, exh. cat. Neuer Berliner Kunstverein, Cologne, Walther König, 2010. See also: Skulpturenboulvard Kurfürstendamm-Tauentzien, exh. cat. Neuer Berliner Kunstverein, Berlin, Dietrich Reimer, 1987.

[5] Cf. Siegrid Adorf, “ Between Private Dreams and Public Space,” Marius Babias, Kathrin Becker, Sophie Goltz, Time Pieces. Videokunst seit 1963, Cologne, Walther König, 2011, 84.

[6] It is up to the individual viewer to judge for themselves whether with the staging of a naked white female body in front of the video camera, Vostell—artistically against his better judgement—is continuing what the feminist-inspired art criticism coming from women artists and historians had begun in the 1960s: the questioning and deconstructing of the figure of the predominantly White Muse (in the form of a staged naked body with the characteristics of female genitals) in art history.

[7] Cf. Aktionen der Avantgarde (ADA 1), published by the Neuer Berliner Kunstverein, exh. cat., Berlin, 1973.

[8] Cf. Aktionen der Avantgarde (ADA 2), published by the Neuer Berliner Kunstverein, exh. cat., Berlin, 1975.