Jenny Dirksen on

Ulrike Rosenbach

On Friday, December 3, 1976, the ballroom of the Neue Galerie – Sammlung Ludwig, the predecessor institution to the Ludwig Forum, was the location for the premiere of Ulrike Rosenbach’s performance 10,000 Jahre habe ich geschlafen (For 10,000 Years I’ve Slept). The elements making up the performance were a circular expanse of salt six meters in diameter and within this a smaller circle of moss, on which the artist, dressed in white leotards, lay curled up on her side, clamped, like an arrow about to be fired, in a bowstring made of bamboo. Attached to a track system, a camera moves around her, its lens pointed directly at the artist, its view of the main action transmitted to the public via two monitors. The noise of the traveling camera mixes in with an electronically processed sound. The artist remains motionless and silent for three hours, before she breaks out of her taut position and the bowstring, interrupts the path of the camera by setting off a short circuit, and writes in the salt: “For 10,000 years I’ve slept and now I have awakened.”

Zehntausend Jahre habe ich geschlafen, 1976, video stills © Ulrike Rosenbach, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

The performance was part of the solo exhibition Ulrike Rosenbach. Foto – Video – Aktion, which opened on that very evening. It was one of the artist’s first solo exhibitions in an institutional setting. Ulrike Rosenbach had studied in Düsseldorf, with Joseph Beuys her last teacher. She purchased her own video camera as early as 1971. In the first half of the 1970s, curators like Lucy Lippard, Willoughby Sharp, and Wulf Herzogenrath included her works in group exhibitions. By 1976, Rosenbach had already visited and stayed in New York and California on several occasions, and was thus familiar with the artists and issues of both American Body Art and feminism. In 1977, she moved to Cologne and founded there a school for “Creative Feminism,” as well as—together with fellow artists Klaus vom Bruch and Marcel Odenbach—the group ATV (Alternative Television), which campaigned for making video art accessible through the broadcasting network used by television stations. These are only a few of the key markers during the years in which Rosenbach emerged as one of the most important protagonists of video and performance art in Germany.

In 1978, together with Klaus vom Bruch, Rosenbach hosted a symposium at the Neue Galerie – Sammlung Ludwig titled Performance – Ein Grenzbereich, which approached performance as an artistic medium spanning genres and provided a platform for the staging of a number of performances. In 1986, another exhibition at the Neue Galerie followed. The vast number of videos from the years 1975 to 1984 in the archive of the Ludwig Forum is thus no surprise. The video documenting 10,000 Jahre habe ich geschlafen is amongst them. The motionlessness of the action is unusual for Rosenbach’s work up until this point in time. Most of her artistic work in the 1970s is characterized by repetitive, often rhythmically structured performances, which Rosenbach herself called “video-live-performances.”

Sorry Mister, 1974, video stills © Ulrike Rosenbach, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

For example, in Sorry, Mister (1975) the viewer sees a hand slapping a thigh again and again, accompanied by Brenda Lee singing “I’m Sorry,” a 1960 hit. A close-up allows one to observe how the skin turns red. The singer’s imploring apologies and the rhythmical slaps run synchronously and reinforce one another in the contrast between a conventional song and a controlled, merciless act outside the norm, carried out in front of a camera that stands by like a witness.

Glauben Sie nicht, daß ich eine Amazone bin, 1975, video stills © Ulrike Rosenbach, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

The organizing structure of a repetitive activity that follows a clear pattern is also essential to Glauben Sie nicht, daß ich eine Amazone bin (Don’t Believe I’m an Amazon, 1975). A reproduction of Madonna im Rosenhag (ca. 1450) by Stefan Lochner is superimposed with a shot of the artist, equipped with bow and arrow as an Amazon. She takes aim at the face of the Madonna and fires. With her own face superimposed, the arrows are thus striking her as well. Amazon and Madonna—here they stand for two contrasting, and yet inextricably intertwined, constructions of the female role.

Reflektion über die Geburt der Venus, 1975–1976, video stills © Ulrike Rosenbach, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Rosenbach also works with superimposing in Reflektion über die Geburt der Venus (Reflection on the Birth of Venus, 1975/76). Here it is the main figure from the Birth of Venus (1485/86) by Sandro Botticelli whose face is superimposed with the artist’s image. The artist slowly turns full circle. Thanks to the split colors of her leotards, the front white and the back black, the image of the Venus in the scallop shell alternately appears and then disappears again. The artist is the moon to the goddess Venus born in the sea, accompanied by Bob Dylan’s “Sad-Eyed Lady of the Lowlands” (1966).

The preceding descriptions make it clear that Rosenbach uses a number of elements repeatedly, for example closed-circuit loops and superimposing, which—themselves means to create repetition—are key components in the works. Certain materials and symbols also recur, for instance the bow and arrow. The stereotyped constructions of femininity passed down through generations reappear, while music, sound, and rhythmical repetition are all essential features in her work.

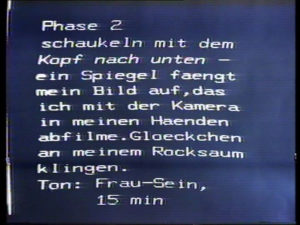

Salto Mortale, Videoaktionen, 1978, video stills © Ulrike Rosenbach, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Salto Mortale (1978) again takes up Lochner’s Madonna im Rosenhag and confronts it with a photograph of Leila Khaled, whose acts of terrorism for the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine made her famous in the late 1960s. Their heads gently tilted towards one another, the juxtaposition of the two women—Madonna with child, Khaled with an AK-47—takes up the contrast from Don’t Believe I’m an Amazon. The camera moves dizzyingly but rhythmically back and forth from one image to the other. The jingle of small bells and wind accompany the camera on its to-and-fro. For the recording, the artist mounted both images above her, while she swung back and forth on a trapeze, bells hanging from her skirt. The camera follows her view. In the second part of the video, one sees the camera itself, two hands around it, reflected in the mirror below her that forms part of the performance: the artist has meanwhile dropped down, swinging from her knees . She repeats the words “Frau-Sein” (“To be a woman”) rhythmically, in a whispering tone.

Tanz um einen Baum (Dokumentation einer Videoaktion), 1979, video stills © Ulrike Rosenbach, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

In Tanz um einen Baum (Dokumentation einer Video-Aktion) (Dance around a Tree [Documentation of a Video Performance]) from 1979, the outward and inward perspectives of the performance alternate: While we see the artist rolling around a tree and at the same time binding herself ever tighter to it, the perspective shifts to that of the artist, who, a camera fastened to her arm, films lurching images of trees, viewers, and high rises, thus incorporating her perspective into the performance.

Jactatio, 1979, video stills © Ulrike Rosenbach, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Both Lotus-Knospen-Töne (Lotus-Buds-Tones, 1979) and Jactatio (1979), also from this period, are based on a single action and focus on a detail. Jactatio focuses on a head tossing from side to side, like the spasms evident with the illness of the same name, and Lotus is made up of two elements: the face of the artist, frontally facing the camera, and the clashing of two chopsticks, which she beats together right in front of the camera, at long intervals and with a loud, abrupt clang.

Psyche und Eros, 1981, video stills © Ulrike Rosenbach, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

In the 1980s, Rosenbach developed structures in her video works that were increasingly complex, frequently still based on performances. Superimposing and overlapping images, part of her artistic practice from the outset, take on the character of a multilayered nesting, enabled by enhanced technological possibilities, so that instead of focusing on reproductions, now collage-like visual elements and text narratives place female figures in the foreground, both real women as well as characters from myths and legends.

Psyche aber – sie irrte gänzlich umher, 1981, video stills © Ulrike Rosenbach, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Psyche und Eros (Psyche and Eros, 1981), like Psyche aber, sie irrte gänzlich umher (But Psyche, She Roamed about Everywhere, 1981), takes up the myth and suffering of Psyche. Increasingly, the image liberates itself from the text accompanying it, spoken from off stage.

Aufwärts zum Mount Everest, 1983, video stills © Ulrike Rosenbach, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Aufwärts zum Mount Everest (Upwards to Mount Everest, 1983) is a fragmentary rendering of the account by Junko Tabei, the first woman to climb the world’s highest mountain in 1975, coupled with associatively arranged visual material, music, and sounds of breathing.

Inner Landscape – Insight Image, 1984, video stills © Ulrike Rosenbach, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Inner Landscape – Inner Insight (1983) takes rushing water, focusing hands in front of a camera, the bringing out of a flower from behind paper being torn, a pondering language turned inwards, and the sound of breathing as the main elements of a composition that proceeds totally free of and without recourse to known figures.

Alle lieben Carmen, 1984, video stills © Ulrike Rosenbach, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Similar to Lotus and Jactatio however is Alle lieben Carmen (Everyone Loves Carmen, 1984), which marks a return to reduced structure. Here, the camera focuses on the artist’s hands and hips in two intertwining details as they move slowly, dancingly, to an aria from Georges Bizet’s Carmen (1875), whose title figure was characterized by her unconventionality but also her entrapment in circumstances. The final image of the artist, shrouded in a scarf, her eyes blocked by a strip showing the hands which keep on dancing, goes back to the interfusing of an image of the self and images of archetypical women already evident in earlier works.

Die Eulenspieglerin, 1984, video stills © Ulrike Rosenbach, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Die Eulenspieglerin (1984) is chronologically the last of the works represented in the Ludwig Forum’s video archive. This work uses documentary material of a performance, but in its composition goes far beyond this material. Taking up the figure of a female Eulenspiegel, a revaluation of the social outsider as the mirror of a society, Rosenbach moves expansively through a papered stage setting. She draws, crawls, and rolls around, accompanied by her voice, which describes from off stage the female Eulenspiegel’s journey through life. Rosenbach had already touched on this motif of being on one’s way without ever arriving anywhere in her Psyche works, with the aspects of imprisonment and the predominant goal of liberation and transformation broached there now explored in greater depth. In this sense, Rosenbach’s oeuvre can—and indeed must—be approached and understood as emancipatory at its core. The ritual-like action sequences work through traditional and cliché-fraught images, transmuting them and increasingly dissolving them into the fabric of her oeuvre.