Stefanie Zobel on

Michael Druks

If it is true (and I think it is so) that the camera is the toy gun of grownups, I would not like to be considered a professional cameraman, video maker or film maker. I use a variety of techniques: drawing, photography, collage, writing, tape recording and video tapes. My work is mainly concerned with group and individual behavior in the environment. I focus on the conflict between the individual and the crowd. MICHAEL DRUKS, 1977 [1]

Michael Druks is an artist from Israel equally adept in working with video, painting, and other creative media. These include performance, photography, collage, and installation. Within this media portfolio, film is far more than just a “toy gun,”[2] as he puts it above; while a medium of documentation, it is also suitable for audiovisual analysis and aesthetic elaboration. As the quote makes clear, Druks is interested in exploring questions confronting the individual in social and political contexts. Among other places, Druks’s work has featured at documenta 6 of 1977 in Kassel, the Centre George Pompidou in Paris, the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) and the Whitechapel Gallery in London, and the Tel Aviv Museum as well as other exhibition venues in Israel.[3] In 1977, he also presented an important performance at the Neue Galerie in Aachen, today the Ludwig Forum, which was the basis for the video work Territory – Living Space. Ten years ago, a retrospective, Michael Druks: Travels in Druksland, held at the Museum of Art, Ein Harod, paid tribute to his oeuvre.[4]

Born in Jerusalem in 1940 and having grown up in Tel Aviv, Michael Druks has lived and worked in London since the 1970s. He completed his artistic training at the Bat-Yam Art Institute and the Advanced School of Art in Tel Aviv. In this early phase, he concentrated on painting. He was also active in theater. Beginning in 1968, his work featured in exhibitions, and in the following years, this extended to all of the significant exhibition projects in Israel.[5] In the 1960s and 70s, he was a key representative of the younger generation of artists in Israel who combined experimental theater, painting, and graphic mapping with the still young genre of video art.[6]

After spending several months in Amsterdam before moving to London in 1972, Druks expanded the scope of his artistic practice to include video, body-related performances, and mapping.[7] Embedded in this field of tension between the body and its mapping, this artistic orientation placed his work in the major contemporary discourses of the international art scene, as is evidenced by his exhibition vita. In the 1970s, he was one of the very few artists from Israel to feature in the important art institutions of Europe and North America. It is only since the 1990s that artists from Israel have gained greater visibility abroad. Galia Bar Or has underlined how Druks has never forgotten his Israeli background and the art public there, exhibiting his work regularly in his home country.[8]

Tellingly, he adopts an in-between position: “I settled in London not to be British but to be between conditions.”[9] He uses this in-between space to explore a variety of themes, for instance questions of identity, the relationship between the individual and the collective, and how the body moves in and interacts with space. „His early work revolves around questions of mental and physical mobility, the complex relationship between humans and space, the political, symbolic, and metaphysical meanings associated with it, and the critical, democratic, but for that the leveling potential of public media.“[10]

The political dimension of space and territory, in tandem with the important role played by the medium of film, is broached in one of his main works.

Territory – Living Space, 1977, video stills © Michael Druks, courtesy England & Co gallery, London

In Territory – Living Space (1977) a knife flies across a circle marked on a patch of sand. Two men face up to one another. One of them marks his territory in the sand. We are witnessing a fight being played out, archaically in sand, or so it seems at first. The camera pans away somewhat, filming the sandy ground from a bird’s-eye perspective and the protagonists at the perimeter, who take turns throwing the pocketknife onto the ground. In black-and-white, the circle resembles a map or a world disc—a microcosm of the macrocosm. A metaphor, it would seem.

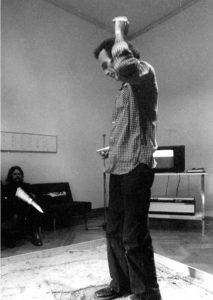

Michael Druks was invited to stage a performance at the Neue Galerie – Sammlung Ludwig in Aachen on May 5, 1977. Together with a volunteer,[11] he himself was a protagonist in Life Space / Lebensraum – Territory / Land Erobern.[12] Filmed as a video performance, this work was intended by Druks as an independent work of art, not merely documentation. At a very early point in time, the Neue Galerie in Aachen had thus brought to the public a position otherwise unknown in Germany. The historical and political significance of this work continues to resonate down to the present day, with the work included in the thematic exhibition The Hidden Trace: Jewish Paths through Modernity held at the Felix-Nussbaum-Haus, Osnabrück.[13]

Michael Druks performing Territory – Living Space for the first time, Neue Galerie – Sammlung Ludwig, Aachen, May 5, 1977, © Michael Druks, courtesy England & Co Gallery, London

Druks takes up a children’s game he was familiar with in Israel: “Territory.” A circle is drawn on a patch of sand; the circle is then divided, so that each half is the land belonging to one of the respective players. With the game set up, each player now throws a penknife onto the territory of the opponent. The expanse of this “territory” is continuously reduced until one player no longer has any space left to stand on. Here space is mapped and marked, one’s own and that of the opponent, or indeed that of an enemy.

“Children’s games and activities very often mirror and symbolize adult situations and also present emotions in a very visual and sensual way.”[14] Tellingly, the performance takes place in a sandbox—a place for children/adults to play. The interaction between the players has a moving, and emotionalizing, component: „The performance itself is an emotional experience, while the resulting video tape (taken from above) emphasizes the esthetic values: the constant change in material and shapes occurring during the game. In the game I am fascinated by the sharp contrast between the abstraction of the visual effect and the realism of the competition using a penknife (almost a real weapon).“[15]

Michael Druks performing Territory – Living Space for the second time, Tel Aviv Museum of Art, 1998, © Michael Druks, courtesy England & Co Gallery, London

Throwing a penknife clearly touches on a political dimension as well. A newspaper article from 1977, included in the publication commemorating the first ten years of the Neue Galerie – Sammlung Ludwig, refers to this context: “Michael Druks is Israeli. The performance at the Neue Galerie showed, on a television screen, the dividing of sandy land with a knife […]. Foreknowledge makes the performance understandable. It triggers concern.”[16] Beyond the immediate association of the territorial conflict in Israel, the location of Aachen means that the game also raises the sensitive issue of German-Israeli relations.

In reference to this, Michael Druks has said: “Don’t forget that I am an Israeli living in London and performing in Germany. […] I performed it in Aachen (1977) against a German volunteer. In 1998 I performed it in the Tel Aviv Museum (Perspective on Israeli Art in the Seventies), I performed against an Arab-Palestinian volunteer. As far as I remember, in all […] cases I let my opponent win.”[17] The artistic gesture, expressed in the seeming simplicity of a children’s game, can thus also be interpreted as a genuine political gesture of peace.

Test N° 3 (Drawing) – Everybody’s Own Square, 1975, video stills © Michael Druks, courtesy England & Co gallery, London

Playing in the Play-Box and cartographies of the artists’s own territory – Druksland: additional major works by Michael Druks

As way of comparison, consideration shall be given to Michael Druks’s first video work, Play-Box (video, b&w, 5:26 min, Royal College of Art, London) from 1973. This work looked at the omnipresence of television in society. In the media-critical video, Druks interacts as a protagonist with the mass medium of television. In the first part, he seems to be trapped in the television set—the Play-Box—and presses his hands from inside the set against the glass. He peers outward as if looking through a transparent screen. Here he is reversing the one-sided viewer-sender relationship, as if he were arranging and showing the program from within. With the playful wink of the artist, he takes up the criticism of the media that was widespread at the time.[18] In the second part of the work, we see a stereotypical living room with its staid ambience; Druks himself moves about the room, all the while seeking to subvert the one-dimensional broadcasting of information and ideologies in television through various interventions, even going as far as stripping naked to distract from the ever-present stream of television. However, simply turning off the set and breaking the omnipresent spell of the program seems to be impossible.[19] This is the main statement put forward by the video, employing a host of humoristic interventions: “Druks’s first videotape: failed attempts to ‘switch off,’ to shut the mouth and eyes of the television face, to ‘disturb’ the television program.”[20] Although the position taken is by no means unique in terms of its media critique, cross-linked in a broad network of historical artistic practice, the specifics of how the media interaction was implemented have remained etched in the memory of the curatorial world. In a recently initiated public program, Staring Back at the Sun: Video Art from Israel, 1970–2012, Play-Box was shown at the New Museum in New York, praised as an important exemplum from the 1970s, and it has featured as part of exhibitions or screenings at a number of international museums including the Tel Aviv Museum of Art.[21]

Besides videos, there are prints by the artist that gained even greater fame and were featured in numerous publications, foremost among them the lithograph Druksland (1974-75, offset print, color, 44 x 34 cm, from: Flexible Geography (My Private Atlas), 1971–1979, an album of 25 works on paper, collection of the Tel Aviv Museum of Art), a self-portrait. Visualized like a “physical and social”[22] map, the shape of the artist’s head matches the contoured terrain of Druksland. Thus, interior (emotional and mental) worlds and exterior worlds merge.[23] Druks has transformed the classical art-historical genre of the lithograph into an unconventional map of the self and his own country—Druksland. With this artistic cartography, he measures and surveys the “occupied territory”[24] in himself and, in a broader sense, that of his native country. „Of course Druksland is also political, the borders, the occupied territories, the situation in Israel, the names and places of people—my parents and so many others with whom I was close back then. Even Walter Benjamin is mentioned. If a name appears here, then it’s because it has something to do with my thinking.“[25]

To research his own self and the cultural and social context, Druks used mapping, an approach that has become even more important as a creative method since the onset of the spatial turn.[26] Galia Bar Or has pointedly described how cartography, the body, and measurement are interrelated: “Mapping, which begins with measurement, is therefore a projection of the body onto space.”[27] The artist himself explains his cartographical approach by comparing it to language: “Why a map? Because maps are a kind of Esperanto, a shared language that knows no barriers. In this sense I used the geographical language to express myself.”[28] These considerations are of particular interest with respect to the spatial dimension of the video work discussed below.

Test N° 3 (Drawing) – Everybody’s Own Square, 1975

A flickering black-and-white film begins. Shaky, very bright moving images are to be seen, and then it starts in earnest: a hand clumsily draws a square on a blank sheet of paper, now a hard cut follows. A man stands in front of the camera, arms stretched out to the sides. One immediately thinks of stretching exercises—or Leonardo’s famous drawing of a body in classical proportions. Suddenly, the camera jolts around in a more experimental manner. The association of the Vitruvian ideal measurements quickly vanishes.[29] Another cut. A piece of graph paper is attached to a wall. To conclude, all is commingled. Through cross-fading, the man with the outstretched arms stands in the square drawn by the hand; the graph paper is underlain as background. Then a cut, a new hand, and it all begins again. Twelve persons and their very personal squares are visualized.

The subtitle of the video related here in impressions is: Assessment of Size Relationship. The whole work complex of Everybody’s Own Square (1975, photographs, b&w, each 25.15 x 15 cm, Whitechapel Gallery, London) comprises photographs, photomontages, and the video tape. Like Territory, the latter belongs to the early and—until the research undertaken by the Video Archive project[30]—almost forgotten collection of video art of the (former) Neue Galerie, today the Ludwig Forum Aachen.

For the moving image work Test No. 3 (Drawing): Everybody’s Own Square (video, b&w, no sound, 16:15 min., Internationaal Cultureel Centrum (ICC), Antwerp, and Neue Galerie Sammlung Ludwig, Aachen), Druks superimposed three shots to visualize the study of proportions: first, the drawn square; second, the participants in the stretched-out pose; and third, the mathematically precise graph paper. In the catalogue for the show at the Whitechapel Gallery, he recorded this veritable experimental setup in writing and flanked it with scientifically inspired deliberations.[31] Despite taking the approach of an exploratory study, the work maintains a playful character aesthetically due to the improvised camerawork and a matching cutting of the video, which shows amateurs in action, similar to how Territory and Play-Box evoke this in more pronounced form on the narrative level. The result of the visual research undertaken in Everybody’s Own Square is the observation that most of the test subjects, contrary to their own assessment, failed to draw a square with mathematically correctly proportions, i.e., four sides equal in length with four right angles.

In contrast, Druks felt he could find a connection between the subjective measurement and the respective body thanks to the superimposing. In other words, eight of the twelve participants created a square by hand in which they fitted better in the projection on the screen with their body measurements than in an ideal square.[32] He elaborates a theoretical consideration on this aesthetically interesting constellation: “Different people relate to a given space in different ways. […] My theory is that each person’s vision is influenced not only by mental factors and personality types but also by physical characteristics, such as the shape, size and proportions of the parts of the body.“[33] From today’s perspective, this direct connection between body measurements and subjective feeling seems merely associative, and questionable as an almost biologistic anatomy conception. And yet, it is precisely this emphasis placed on the subjective perception and the individual vis-à-vis an objectified technologization and anonymizing collectivization of society that, viewed historically, is closely bound to important—and still influential—discourses of the time[34] and, in the specific observation of the hand drawing, produced an important contribution to the artistic exploration of this thematic area.

Michael Druks, Everybody’s Own Yard. A Photographic Study, exhibition at Whitechapel Gallery, London, February 24 – April 4, 1976, © Michael Druks, courtesy England & Co Gallery, London, photo: Michael Druks

Created concurrently, directly connected thematically, and arising out of the same context is the work Everybody’s Own Yard, in which Michael Druks has test persons mark out a yard, the Anglo-American measurement of length. The measurements made subjectively with the individuals’ own bodies deviated from the objective measurement to a similar degree as with the square. Druks took photographs of this action, which he then exhibited as a series at the Whitechapel Gallery in 1976.[35] Both work complexes bring out the difference between individuals and their subjective sense of scale. With the experimental mapping of bodies in their diversity, Druks developed a way of interrelating the individual, physical body, and questions of measurability.

Outlook: Michael Druks‘ current focus on painting

Michael Druks is today artistically active on other paths but just as playful and inquisitive as ever. Painting has accompanied him from his artistic beginnings in Israel to the present day. It first became the focus of his creative output in the 1980s. Abstract scenes, partly figural, partly collages, characterize the later paintings. The colors seem almost random, but the coloration does not function as decoration, nor as the representation of real things. The “unnatural,” seemingly haphazard color schemes emphasize instead the absence—or the impossibility—of authenticity.[36]

“Canvases from the 1980s become mundane artifacts. Druks uses his materials in an unconscious, intuitive manner, toying with them as if he were a child playing with blocks.”[37] Here the artist accordingly pursues the same strategy of play as in the early moving-image works. Even if the aesthetic effect generated differs from the earlier positions, as Galia Bar Or correctly notes, his painted artifacts do not represent a turn away from his oeuvre—on the contrary, like an explorer in foreign lands, he continues to stretch out his hands and measure these territories.[38]

Horizons of meaning in the moving image works of Michael Druks

Play as a cultural praxis is turned into an instrument for artistic measuring—in the end, this is the tenor when considering Michael Druks’s moving-image works, from Territory and Play-Box through to Druksland and Everyone’s Own Square or Yard. Here the individual with his/her body is the protagonist of the always playfully arranged actions. In the process, the body becomes the scale for mapping. Ultimately, this does not mean a scientific measuring in a strict sense, producing spatially related information, but rather an artistic exploration of this topos using mapping strategies and diversely oriented measurements. It is about social territories, also political spaces, which are regarded pointedly in the microcosm of the installations and videos. In these works, the tension between individual versus the collective is a constant of the artistic exploration: “I lived in the Holy Land, which is extremely tribally structured. Nevertheless, my individuality was important to me, and so I’ve held my individuality in high esteem.”[39] Michael Druks’s plea for the individual in his/her social and political spaces is thus not to be read as just a humanistic ideal—it is always a response to his Israeli and Jewish cultural contexts. An artistic and creative engagement with the once collectively oriented founding generation through to today’s current political (and demanded) collectivism in Israel is also highly relevant for German contexts. As early as the 1970s, the Ludwig Forum in Aachen placed this German-Israeli dialogue in artistic action format on its own agenda, and has now put it up for discussion again. On both curatorial and scholarly levels there is still much to be examined and discussed.

[1] Michael Druks, quoted from: Photography as Art, Art as Photography, ed. Floris M. Neusüss, vol. 2, Kassel: Fotoforum Kassel, 1977, 4.

[2] Cf. the quote in note 1.

[3] See the press release of March 2013 by the England & Co. Gallery, who represent the artist and have shown his work in group and solo exhibitions: https://www.englandgallery.com/michael-druks/ (last accessed January 11, 2016).

[4] Michael Druks: Travels in Druksland, ed. Galia Bar Or, exh. cat. Museum of Art, Ein Harod, Israel, 2007.

[5] See the catalogue accompanying documenta 6: Manfred Schneckenburger, Documenta 6: Fotografie, Film, Video, vol. 2, Kassel 1977, 335.

[6] See Herbert Kopp-Oberstebrink and Judith E. Weiss: “Michael Druks. Wenn man reagiert, ist man nicht frei. Zur Topografie des Gesichts,” in: Kunstforum International, vol. 216, 2012, 129–135, here 129.

[7] See Galia Bar Or, “Foreword,” in: Bar Or, 2007, 322–321, here 322. In line with Jewish tradition, the page numbering is inverted.

[8] Galia Bar Or, “Introduction,” in: Bar Or, 2007, 320–318, here 320f.

[9] Quoted in Galia Bar Or, “Introduction,” in: Bar Or, 2007, 320–318, here 319.

[10] Kopp-Oberstebrink/Weiss, 2012, 129.

[11] This was Dieter Göllen according to the documents in the Ludwig Forum archive.

[12] The title is cited variously in different publications and is sometimes given as Living Space – Land Gewinnen.

[13] See Die verborgene Spur. Jüdische Wege durch die Moderne, ed. Martin R. Deppner, exh. cat. Felix-Nussbaum-Haus Osnabrück, 2008—2009, Bramsche 2008, 212f.

[14] Statement by Michael Druks in an email of June 7, 2008, to Sonja Benzner, librarian at the Ludwig Forum Aachen.

[15] Quoted from the flyer accompanying the performance, Territory – Land Erobern, eine Video-Performance, n. p., Neue Galerie Aachen, 1977, archive of the Akademie der Künste, Berlin.

[16] See 10 Jahre Neue Galerie – Sammlung Ludwig, ed. Neue Galerie – Sammlung Ludwig in cooperation with Verein der Freunde der Neuen Galerie, Aachen 1980, n.p.

[17] Also taken from the email mentioned in note 14.

[18] See Galia Bar Or, “Play-Box: Video and Television,” in: Bar Or, 2007, 316–297, here 303 f.

[19] Cf. the description of Play-Box by the LIMA: https://www.li-ma.nl/site/catalogue/art/michael-druks/playbox-amsterdam/475 (last accessed: January 11, 2016).

[20] Schneckenburger, 1977, 335.

[21] The renowned curator Ilana Tenenbaum from Israel curated the first part (“1970–1980: Early Experiments in Time-Based Art”); see www.newmuseum.org/calendar/view/630/staring-back-at-the-sun-video-art-from-israel-1970-2012, and www.bravermangallery.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Staring-Back-At-The-Sun_Prospectus_26.1.16.pdf (last accessed January 2, 2017).

[22] This is the explanatory subtitle describing the topographical features of the map that is the offset print of Druksland.

[23] Galia Bar Or, “Flexible Geography: Mapping Works,” in Bar Or, 2007, 296–284, here 293 f.

[24] In Druksland this word group is printed on the forehead of the artist.

[25] See the interview Druks gave in: Kopp-Oberstebrink/Weiss, 2012, 131.

[26] The Map as Art: Contemporary Artists Explore Cartography, ed. Katherine Harmon, New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2009.

[27] Galia Bar Or, “Flexible Geography: Mapping Works,” in Bar Or, 2007, 296–284, here 296.

[28] See Kopp-Oberstebrink/Weiss, 2012, 131.

[29] Cf. Galia Bar Or’s comparison: Galia Bar Or: “Play-Box: Video and Television,” in: Bar Or, 2007, 316–297, here 301f.

[30] See the information on the project page: https://ludwigforum.de/museum/videoarchiv-die-wissenschaftliche-erschliesung-und-prasentation-der-videobestande-des-ludwig-forum-aachen/videoarchiv/ (last accessed: March 11, 2016).

[31] Michael Druks: Everybody’s Own Yard, A Photographic Study, exh. cat. Whitechapel Art Gallery, London, 1976, 3.

[32] Whitechapel Art Gallery, 1976, 3.

[33] Quote from Michael Druks in: Whitechapel Art Gallery, 1976, 3.

[34] See the overview of the historical discourses in Galia Bar Or: “Play-Box: Video and Television,” in: Bar Or, 2007, 316–297, here 301ff.

[35] Whitechapel Art Gallery, 1976.

[36] Meir Loushy, “Michael Druks: View. Material. Thought,”

https://www.loushy.com/innerpage.aspx?code=101 (last accessed February 2, 2017).

[37] Loushy, 2013.

[38] Galia Bar Or, “The Alchemist: The Late Painting,” in: Bar Or, 2007, 254–249, here 249.

[39] Interview in Kopp-Oberstebrink/Weiss, 2012, 130.