Corinna Kühn on

Marran Gosov

Artists who, like Marran Gosov (b. 1933 in Sofia; real name: Cvetan Marangozov[1]), received their training in the 1950s in Eastern Europe were confronted with restrictions early in their careers. The freedom of the arts was limited, just like freedom of expression and freedom to travel. Publications were controlled by the state censor, critical passages deleted, or the work was simply banned. Art exhibitions were also reviewed by the censor and, if deemed necessary, closed. Just as it was all across the Soviet Union, art in the former People’s Republic of Bulgaria was regulated by the organs of the Communist Party, with the Department for Art and Culture prescribing norms and directives which artists had to observe.[2]

Only art and literature that was loyal to the regime was given support. In the eyes of the Bulgarian Communist Party, it was the task of art and culture to mirror the Party’s postulates and serve to spread the propaganda of the regime.[3] In the 1950s this meant in most Eastern European countries that art and literature had to fulfill the aesthetic criteria of “Socialist Realism.”[4] Exhibition themes and the desired genres were specified by the “Association of Bulgarian Fine Artists.” Founded in 1949, its notions of art mostly excluded those forms of representation deviating from the “traditional” genres of sculpture, painting, printing, and drawing.[5] Until the fall of the “Iron Curtain” and even after 1989, photography and video were noticeable by their absence in the Association’s exhibitions.[6] The use of video cameras was subject to strict controls. As Ana Karaminova has noted, it was “impossible to purchase a video recorder and video cameras could only be used in television stations under the state control of professional staff.”[7] Low technological standards and state censorship—even the use of photocopiers was strictly monitored until 1989—made working artistically with the new media, embraced by and increasingly popular on the art scenes in Western Europe and the United States, almost impossible. Whereas in other socialist countries such as the former Polish People’s Republic and the former Yugoslavia there are early examples of video art from the 1970s, there is no known production of video work up until the end of the 1980s in Bulgaria.[8]

Given this non-contemporaneity of media in the art cultures of the “Cold War,” it was one of the preconditions for the video art of the Bulgarian-German artist Gosov that he, after mustering the courage and bracing for the worst, finally succeeded in escaping abroad, to “more video-friendly” countries. Having grown up in socialist Bulgaria, where in the capital Sofia he at times earned his living by drawing caricatures, Gosov was exposed to the regime’s despotism at an early age. In 1951, while still at high school, he undertook his first escape attempt together with a friend, trying to reach Greece. They were caught however and detained as political prisoners. Although after his imprisonment he embarked on a career as an author in Bulgaria, he again tried to escape, this time successfully emigrating, under the pretense of visiting his German mother, to the Federal Republic of Germany in 1960.[9]

Once in West Germany, he met influential figures on the art scene. Through his father, himself a writer and architect, he was able to make contact with the writers of the Gruppe 47 in Munich. This circle of literati received the young political refugee from the Eastern bloc with curiosity. In the midst of the reemerging German film scene in the Munich district of Schwabing, which, influenced by the French Nouvelle Vague, was celebrating bohemian life, Gosov began to write radio plays and scripts before producing short films. After the director Peter Fleischmann had organized his first commission, Gosov shot 28 short films between 1965 and 1975, whereby he was responsible for the script, directing, editing, and sometimes the camerawork. From 1967 to 1972 he was involved in large productions of long feature films for the cinema, by turns taking on the tasks of directing, screenwriting, and editing. Dissatisfied with the conditions and structures in the commercial film industry, he then unexpectedly turned away from film production and in the ensuing years mainly worked as an author and director for West German television series. After releasing three long-playing records in 1976, with which he went on tour, from the mid-1980s onwards he made a name for himself as a composer of film music. With the fall of the Iron Curtain he finally returned to Bulgaria in 1991, where he was able to successfully resume his writing career.[10]

Ur-Zeit, 1980, in: Subjekt – Objekte: Fragmente (Demoband), 1979-1980, video stills © Marran Gosov

Gosov’s creative phase in Munich was marked by a constructive exploration of video art, which occupied an important place in his oeuvre. As early as 1971 he worked on video acoustics.[11] His first video works followed a few years later, primarily performances for an Akai video camera that could only record in black-and-white. The artist reworked the produced video material into video objects, video sculptures, and video installations. The material on a demo tape entitled Subjekt-Objekte: Fragmente (Subject-Objects: Fragments, 1979–80) in the video collection of the Ludwig Forum in Aachen is in color[12] and with accompanying audio, showing five video objects from these years, with the documentation of the single works varying in length from four to fourteen minutes. Gosov filmed these video objects in short takes.[13]

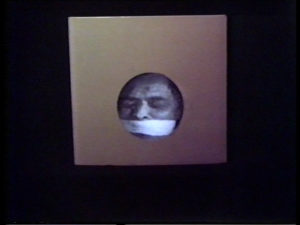

AIFOS I, 1980, in: Subjekt – Objekte: Fragmente (Demoband), 1979-1980, video stills © Marran Gosov

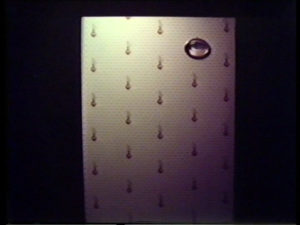

For the work AIFOS I (1979), the artist placed himself in a rectangular cube measuring 66 x 80 x 60 cm, only able to sit with his legs tucked in and curled up into a ball. He recorded his enforced stay in this cramped position with a video camera and microphone. The documentation of the performance was then presented in art galleries as follows: through a narrow slit, barred with wired glass and inserted into a rusty metal box, viewers see only a thin slice of the monitor on which the video of the trapped Gosov is shown. The part of the monitor the gallery visitors can see through the slit shows the artist’s hands, clenched around his feet. This mode of presentation blends together the impression of a live performance and documentation, so that it seems as if the artist is actually pressed into the metal box. A similar work entitled AIFOS II (1980), another performance for the video camera, likewise lasted four hours. The video made during the performance, as with AIFOS I, is presented in the exhibition context on a monitor enclosed in a metal cube. Through a perfectly circular hole in the cube, the head of the artist with his mouth gagged is to be seen on the monitor, a panel of fluted frosted glass positioned in front of it. As a result, the contours and features of the head are only vaguely recognizable. Now and then the nose of the artist seems to be pressed flat against the panel. For the video work Zwiebelwand (Onion Wall, 1980) in contrast, Gosov stared for three hours into a video camera, constantly bringing tears to one eye with onions. As an installation in the exhibition space, the created video material was presented behind a folding screen covered with a Biedermeier-like, onion-patterned wallpaper. Through a small round hole in the upper right corner, bordered by a gold frame, the viewers see the crying brown eye of the artist—this time in color. It blinks and flinches silently. A further work documented on the demo tape in the Ludwig Foundation’s video collection is the installation Ur-Zeit (Primordial Time, 1980). Like the other works mentioned, this work was shown in 1981 under the exhibition title Video Concepts in the Marsyas Gallery, Munich.[14] A monitor positioned on a podium showed a clock with a moving secondhand, which however moves counterclockwise. This reversal was created through a specific arrangement of a camera with a negative switch, a monitor, a quartz clock, and a mirror.[15] Blurred, the numerals swim wave-like on the clock face. Similarly uncanny is an illusion Gosov staged with the installation of a running miniature ventilator that is pointed at a small monitor which shows a white flag blowing in the wind.[16]

AIFOS II, 1980, in: Subjekt – Objekte: Fragmente (Demoband), 1979-1980, video stills © Marran Gosov

When viewing both AIFOS I and AIFOS II as well as Zwiebelwand, the oscillation between staging a shelter and then a prison cell becomes patently obvious, and it is the Kafkaesque plurality of meaning in this oscillation that prevents any obvious categorization of Gosov’s work. The embryonic position Gosov curls up into in the work AIFOS I references a performance of searching for shelter from a hostile outside world, which again and again overlaps in the reception of the works with nightmare-like sequences of torture and imprisonment. Gosov’s heavy breathing[17] is to be heard over loudspeakers, so too his fingers rubbing and scratching his skin: the human in the box has difficulty keeping still and enduring the body position, which prevents the blood from circulating through the arms and legs, causing extreme pain over the four hours. And yet, the viewers are less empathizing and compassionate; their gaze through the slit in the box exposes them instead as prison guards. They move freely around the box, hear the breathing and whimpering of the artist, and are, on the one hand, helpless—there is nothing they can do to free the wedged-in body—but on the other are simultaneously detached from events as uninvolved gallery visitors.

Zwiebelwand, 1980, in: Subjekt – Objekte: Fragmente (Demoband), 1979-1980, video stills © Marran Gosov

The title of both works stems from reversing the name of Bulgaria’s capital, SOFIA, thus referring to the specific traumatic experience of the 18-year-old Gosov imprisoned in a Bulgarian prison as well as confinement in a broader sense, for example the restrictions placed on freedom of expression and travel in the People’s Republic of Bulgaria.[18] The significance of this time in prison for his oeuvre is underlined in the novel he started while in prison, Безразличният (The Indifferent), which, although finished after his release, artistically reflects and digests this experience of deprived freedom. The novel could only be published in a strongly censored version in the People’s Republic of Bulgaria in 1959—reinforcing Gosov’s resolve to leave the country.[19]

Gosov’s approach to the medium of video can be understood in connection with his socialization in communist Bulgaria, where the suppression of access to new technologies fostered an attitude of optimism as to the possibilities afforded by this denied technology, with the medium of video figuring as the only possible transmitter of experiences of living in a communist country. Gosov describes his approach to video as follows:

Since Sofia I can no longer put my experiences into words. In Bulgaria a novel by me was published, but here I need other forms of communication so as to penetrate through all the lies and get to myself. With video I can now work through my inner compulsions by reliving them. One cannot describe pain, you have to go through it.[20]

Performing for the camera and mostly without an audience, the artist triggered this working through of his pain by making use of the potential of the medium to intensify it. In both AIFOS I and AIFOS II his body is not only confined in the performance but moreover the media itself is contained: in the installation, the monitor with the image of the cooped-up body is itself then locked up in the box. This doubling of the confinement augments the “real” body of the performance, which suffered physically and emotionally under the enforced predicament, with a mediatized body that experiences the same thing simultaneously. The two bodies of the suffering artist not only stand for a “doubling of reality,”[21] as Gosov stated in an interview, but also for the multiplication of a remembered reality, which again and again recalls what the artist experienced in communist Bulgaria and, in particular, the prison cell there. Gosov considered the sensibility arising out of this reflective viewing, created with the help of video, to be positive.[22]

By the early 1980s at the latest, the critical discussions on television taking place in avant-garde circles in West Germany started to resonate in Gosov’s ideas on the possibilities of the medium of video. In a 1981 interview he emphasized that his video art should be read as a way of dissociating from the “boring” medium of television.[23] He expressed a sense of uneasiness with television: “One essential negative about television is this subjectivization. The excerpt is always a lie and television is always condemned to the excerpt because it can never depict anything complex.”[24] This understanding of the “excerpt as a lie” is mirrored in another video installation,[25] which Gosov also exhibited in Munich’s Marsyas Gallery in 1981: While the word “GEMEINSAM” (“TOGETHER”) was plastered on the gallery wall in black letters, on a monitor next to it appeared the word “EINSAM” (“LONELY”), produced with a small video camera.[26] In video art, the artist was seeking “the opposite of what television does, which normally claims to announce the truth, to document events authentically.”[27] Such remarks reverberate with the critique of the all-appropriating “culture industry,” which also included television, elaborated by the older Frankfurt School generation around Theodor W. Adorno and Max Horkheimer. But whereas the West German avant-garde and intellectual scene, for example Alexander Kluge since 1988, were searching for an “alternative television,” Gosov was more interested in the sculptural qualities of the monitor and dreamed of workshops in which he could cast or blow monitors in specific forms and connect these with compositional ideas.[28]

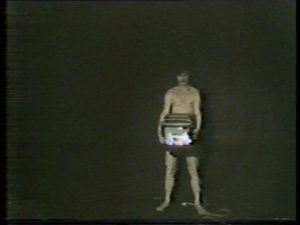

Schutzlos unverwundbar, 1980, in: Subjekt – Objekte: Fragmente (Demoband), 1979-1980, video stills © Marran Gosov

While the statements above seem to indicate that Gosov perceived a loss or lack of “authenticity” in television, his critical performances were in fact playful, shifting back and forth between mythological references and stark criticism of consumerism. In a performance entitled Schutzlos-unverwundbar (Vulnerable-invulnerable, 1980), also documented on the Aachen demo tape, he showed television to be a kind of “burden” for modern humans: For two hours and in the presence of an audience, dressed only in black underpants, the artist—as if doing an elaborate gymnastics routine, squatting, lying, standing on one or two legs—carried a color television on his shoulders, held it high above his head, balanced it on his feet or knees, and even threw it into air, until his arms and legs tired out. Showing on the monitor, by coincidence, was the show “Club 2” from the Austrian broadcaster ORF, reporting on the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan.[29] Here Gosov turned the titan Atlas, who in Greek mythology carries the whole world on his shoulders, into a messenger spreading an uncomfortable truth: “For many, the only connection they have to the world is the television at home.”[30] The regret resonating in this statement relates to idealized notions about the opportunities to travel, see and experience things, and educate oneself through books and discussions, factors which have all shaped Gosov’s biography since he fled communist Bulgaria. As he saw it, the TV programs of the time lacked innovation.[31]

For the artist, filming with the video camera therefore remained an antipode to the television program, a role he inferred not least from the anti-elitist potential of the technology, and for which reason Peter M. Bode characterized him as a “videalist.”[32] The possibilities afforded by the video camera stood for accessibility and constant availability at low cost, as Gosov once underlined in an interview: “One can forget the thing, you don’t notice it and you don’t hear it. You don’t have the feeling that you’re wasting material and money. You’ve got sound and image.”[33] Whether professional artists or not—everyone can create what they want, “at home in privacy and without some authority [looking on].”[34] Lines like these show that Gosov had internalized the principle, controversial but widespread in the 1970s and 80s, that “Everyone is an artist!” Here his acquaintanceship with Joseph Beuys, with whom Gosov shot the film Zeige deine Wunde – Aufbau des Environments on video in 1980, becomes noticeable.[35] Not to allow oneself to be mesmerized by the television screen, but to use video as an aid to control it, this is something everyone could and should do in his view.[36] For Gosov, the medium of video ultimately embodied democratic values, which he did not first discover in his Munich exile but probably learned to put into practice there for the first time. In this sense, video art was a potentially controversial medium that not only enabled the Bulgarian émigré, while in exile, to remember the terror he had experienced on the other side of the Iron Curtain; gradually he also began to doubt the promises held out by the consumer and television world which dominated the reality of everyday life in West Germany. His medialized performances and video installations (re-)produce these overlapping realities and critically scrutinize them at the same time.

[1] Also transliterated in German-speaking countries as Tzvetan Marangosoff.

[2] Founded in 1944, the Ministry of Propaganda exercised direct control over all educational and cultural activities in the country. A department for “Art and Culture” existed up until the early 1960s only within the broader section of “Propaganda and Agitation.” See Ana Karaminova, Bulgarische Videokunst. Dokumentarische Strategien und Gesellschaftskritische Aspekte, Berlin 2015, 18.

[3] Ana Karaminova (see note 2), 18.

[4] I have examined in detail in my doctoral thesis the situation and position of artists in Eastern Europe who refused to meet the demands of official cultural policy and sought alternative possibilities of communication. See also my research project at the University of Cologne, “Das subversive Potential des agierenden Körpers. Medialisierte Performances und Aktionen im Kontext der Neoavantgarde(n) Ostmitteleuropas ab 1960.”

[5] Membership, securing financial independence and providing exhibition opportunities, was highly sought after by artists, although it was by no means stringently required. Ana Karaminova (see note 2), 19.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid., 19. Karaminova points out that the situation in Yugoslavia was different at this point in time. Due to a far more open socialist system, the Culture Ministry in Yugoslavia (above all in today’s Slovenia) not only allowed artists to use video technology as early as the 1980s but moreover made available the montage labs of state television.

[8] Ibid., 17.

[9] I would like to thank Bernhard Marsch, who represents the artist in Germany, for the biographical information on Gosov. Marsch actively works to raise Gosov’s profile in Germany and distributes his short films. See in this connection Bernhard Marsch, “Kurzfilmspecial: Marran Gosov,” in: https://deutsches-filminstitut.de/blog/kurzfilmspecial-marran-gosov/ (last accessed January 19, 2017).

[10] I would again like to thank Bernhard Marsch for the information concerning Gosov’s biography. See note 9.

[11] Wulf Herzogenrath (ed.), Videokunst in Deutschland. 1963–1982, exh. cat. Kölnischer Kunstverein et al., Stuttgart 1982, 295.

[12] Created during the performances, the video material is in black-and-white. The video material on the demo tape in the video collection of the Ludwig Forum in Aachen is a documentation of Gosov’s video objects in an exhibition context, filmed in color.

[13] The material recorded on the demo tape is thus made up of excerpts of the respective video works.

[14] See Armin Kratzert, “Marran Gosov,” in: Video-Kontakt. Magazin für Video, Film und Fernsehen 6, 1981, 79–80, as well as the catalogue to the exhibition Video Concepts in the Marsyas Gallery, Munich 1981. Another exhibition of video work where Gosov’s work was shown was Video. Video Installations by Munich Artists, which was held in 1981 as an accompanying event to the symposium European Video Libraries, Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus in the “factory” venue there. In 1982/83 Gosov’s video installation V/1981 was part of the exhibition Video Art in Germany. 1963–1982, presented at the Kölnischer Kunstverein and other venues and curated by Wulf Herzogenrath (Wulf Herzogenrath (ed.), Videokunst in Deutschland. 1963–1982, exh. cat. Kölnischer Kunstverein et. al., Stuttgart 1982, 174.) The exhibition, shown at several museums, featured all of the contemporary positions in the field of video art and sought to bring together German video artists. Some years later, in 2002, Gosov was invited to the 25th Biennale in São Paulo, where he exhibited the work Video Concept IV (1979–2000). The catalogue is available online: https://issuu.com/bienal/docs/namec39464 (last accessed on January 30, 2017).

[15] Armin Kratzert (see note 14), 79–80, as well as the catalogue to the exhibition Video Concepts in the Marsyas Gallery, Munich 1981.

[16] See the catalogue to the exhibition Video Concepts in the Marsyas Gallery, Munich 1981. This work is not documented on the demo tape in Aachen.

[17] In AIFOS II viewers can also hear the heavy breathing and at times whimpering of the gagged artist.

[18] When Peter M. Bode sees a reference to the “psychiatric” treatment of Soviet regime critics in the work AIFOS II, then this points in the right direction; the more probable source of inspiration is however the autobiographical situation of Gosov’s imprisonment. See Peter M. Bode, “Das Auge weint aus dem Goldrahmen,” in: Feuilleton der Abendzeitung München, March 7, 1980, 19.

[19] The novel has meanwhile been published uncensored in Bulgaria. Цветан Марангозов, Безразличният, Оригиналът. 3-то, прераб. изд., София 2000. (Cvetan Marangozov, Bezrazlitschnijat, Originalut. 3, reworked edition, Sofia 2000.) Bernhard Marsch provided this information on January 25, 2017.

[20] Peter M. Bode (see note 18), 19.

[21] Interview by Gabriele Rettelbach with Marran Gosov, in: Video-Kontakt. Magazin für Video, Film und Fernsehen 1981, 80–81, here 80.

[22] Peter M. Bode (see note 18), 19.

[23] Interview by Gabriele Rettelbach with Marran Gosov (see note 21), 80.

[24] Ibid.

[25] The documentation of this video installation is not on the demo tape in the video collection of the Ludwig Forum in Aachen.

[26] Armin Kratzert (see note 14), 79.

[27] Interview by Gabriele Rettelbach with Marran Gosov (see note 21), 81.

[28] Ibid.

[29] I would like to thank Bernhard Marsch for this information. See note 9.

[30] Peter M. Bode (see note 18), 19.

[31] Interview by Gabriele Rettelbach with Marran Gosov (see note 21), 80.

[32] Peter M. Bode (see note 18), 19.

[33] Interview by Gabriele Rettelbach with Marran Gosov (see note 21), 80.

[34] Ibid., 81.

[35] The film shows the preparatory work for Beuys’s environment Zeige deine Wunde (Show Your Wound) at Lenbachhaus in Munich, as well as a discussion with Alois Hundhammer, who rejected Beuys’s work. Thanks again to Bernhard Marsch for this information during a conversation on January 25, 2017, in Cologne. See note 9.

[36] Armin Kratzert (see note 14), 80.