Lou Jonas on

Leo Copers

In the 1970s, many artists turned to video as a medium. While some made it their main artistic medium, many viewed it as an additional tool to express an idea or action over time. They often used it transiently, alongside other techniques, focusing less on identifying the specific qualities of the medium than exploiting its communication and recording properties.

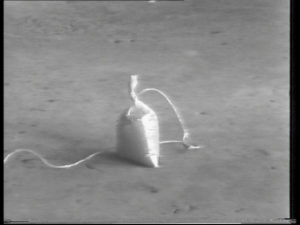

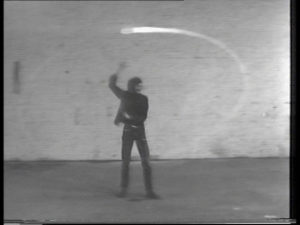

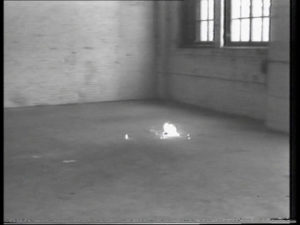

9 Sculpturen, 1974, video stills © Leo Copers, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Leo Copers is a multidisciplinary Belgian artist. His work combines the worlds of myth and imagination while delivering a critical vision of art and its conventions. He works in the fields of painting and sculpture, installation, performance, and photography. He discovered video in the early 1970s, encouraged by his friend and colleague Filip Francis[1]. In 1974, in the private setting of Francis’s Antwerp studio, Copers directed 9 Sculpturen (9 Sculptures), an action for a camera. This piece was initially a performance, first presented during the third edition of the Triennale in Bruges. Copers then decided to re-enact it in front of a camera, without the audience, who would be able to experience it after the event. In this performance, nine found objects, treated as sculptural forms, are successively set into motion by the artist: a cloth, a piece of tree branch, a stone, a bag filled with sand, a bag filled with water, a flame (coming from what looks like the base of a petroleum lantern), a round incandescent lamp, a fluorescent tube, and some glass debris. These are attached to the end of a rope (or to an extension cord connected to the electricity mains, in the lamps’ case) that the artist lifts above his body. In wide circular movements, he casts the objects onto the wall behind him. The camera follows this process, changing the size of the frame as the action goes ahead. For each of the nine objects, close-up frames and overviews alternate, thereby exposing three different stages: the original object, its movement, and finally, the result of this impact. In this specific case, video is not used merely to keep a record of the performance. It is a work of art in itself, in which the camera has a role to play. However, in the 1980s, Copers did produce some video documentation of the same performance, which he presented again in front of an audience at the Atelier 340 in Jette.

With these repeated actions, Copers explores the link between creation and destruction. Once broken, the branch splits. The glass shatters into a thousand pieces. The water and the sand spill out onto the floor. The neon’s intense light leaves an imprint on the camera’s vidicon. Explosion and shattering allow new forms to arise. The sculptural material disperses and reorganizes itself. The artist instigates the process, risking his own life (this is particularly true when the stone is dropped or when the electric lamps are being manipulated). A poetic and ephemeral creation emerges from the violence of the gesture, modelled with the help of the camera’s lens.

Leo Copers, Untitled, 1974–75, Installation with Mona Leo, 1974–75 (left) and Study after Masters, 1974 (right), Centraal Museum Utrecht, © Leo Copers, photo: Ernst Moritz

Danger is a central theme in Leo Copers’s work. In 1969, he directed Waterlamp (1969), in which he placed an incandescent lamp on the surface of a basin filled with water, creating an unstable situation between two elements, making their cohabitation seem possible[2]. The risk of electrocution was however all too real for anyone who might have attempted to touch the piece. The threat was also palpable in Vliegende messen (Flying Knives, 1974), in which two sharp knives cut the air in a continuous rotation at the audience’s throat-level. The underlying idea behind the aggressiveness of the device is to restore a faculty of action and a proper territory to the work of art. Indeed, for Copers, an artwork must be able to “defend itself” against the viewers and the superficiality of their gaze. It is up to them to ascertain the danger of venturing too close to the piece. But the viewers are strongly advised to proceed with caution and the artist declines any responsibility in the event of an accident.

Copers further encourages the viewer to take an active role in projects such as the VIPAG, or PIVAJ in English (Public Individual Voluntary Automatic Jail), an individual public prison, the prototype of which he designed in 2001–2002. He invites willing individuals to insert a coin in the slot meant for this purpose before entering the prison. The doors then close on them for a limited duration, depending on the amount paid. Various placards attached to the prison explain the meaning of the piece in Dutch, French, English, and German. A special caption also reads: “To be used at your own risk.” This confessional-like prison was installed several times in the public space and, in particular, on the Maastricht Vrijthof in 2004, in conjunction with the internationally renowned TEFAF (The European Fine Art Fair).

In his work, Copers constantly stages situations that question the reception of art, both as the audience’s view of the piece and as the discourse held by critics and museum institutions. Just like his fellow citizen Marcel Broodthaers, he led a real guerrilla-type war against the institution from the 1970s onwards. He embodied a blind man and wandered through museum galleries (De Blinde Ziener [The Blind Prophet], an action performed for the first time in 1977 at the Centre Pompidou, and later radicalized with Duister Museum [Dark Museum], in 2001, when the artist immersed the Museum of Fine Arts of Ghent in darkness during visiting hours), and he later designed a cynical memorial consisting of a set of tombstones bearing the names of museums of antiquity, fine arts, and contemporary art (Museakerkhof [Museum Churchyard], a project illegally installed in the park of the Citadel of Ghent in 2012).

Furthermore, Copers practices appropriation to demystify art and to denounce the superficial nature of the discourse held on art. He pays tribute, not without some form of irreverence, to the works of Van Gogh, Magritte, and Marinetti. He also created a series of replicas of Rodin’s Thinker, of which the final version, a thinker who buries his head in the sand, will be visible until November 2017 in the park of the Castle of Seneffe[3].

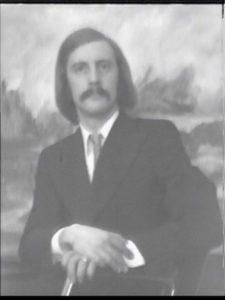

Mona Leo, 1974, video stills © Leo Copers, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

The multimedia installation Mona Leo (1974), in which painting and video co-exist, remarkably illustrates this appropriation tendency. It consists of two parts, which take the iconic figure of the Mona Lisa as their subject. The first, separately named Studie naar Meesters (Study after Masters), is a painted reproduction of the famous portrait of the Mona Lisa by Leonardo Da Vinci. On the back of the painting, Copers adds a device containing water that floods the face of Mona Lisa with tears. This deflection of the original piece generates a first contrast between the liveliness of a smile versus the sadness of tears. It also extends the study of a “motionless motion,” as the flow of tears brings movement and duration to a still image.

Opposite the painting, Copers installs a monitor broadcasting a repeating video sequence (loop) showing a frame of himself in a half-length self-portrait in the pose of the Mona Lisa. The artist sits in front of a painted background that roughly reproduces the landscape depicted in Da Vinci’s painting. In addition, he displays a mustache that doubles the process of appropriation by directly quoting Marcel Duchamp’s famous readymade, L.H.O.O.Q. (1930). This second-degree appropriation also refers to the title of the first part of the installation, Studie naar Meesters, which refers to the many masters who made this masterpiece an object of study.

Copers holds the pose, motionless and serious, for a time that seems infinitely long, as if time were suspended. The viewer comes to doubt the animated character of the image. This uncertainty mounts, until a resounding and shrill laughter erupts every ten minutes, marking the end of the sequence. Intrigued, the viewer is tempted to concentrate more on the video and can then perceive the intermittent blinks of Leo Copers’s eyes, thereby reintroducing movement to the image.

The Mona Leo installation contains a multitude of contrasts: tears / laughter, seriousness / smile, immobility / movement, feminine / masculine, past / present. Ultimately, it confronts two distinct means of expression: on the one hand, the tradition of painting, and on the other hand, video, a new technique for the time. This confrontation is particularly evident in the way the monitor is staged. Opposite the painting and at the same height, it is placed vertically on a pedestal, a reversal that refers to the classical format of the portrait.

Copers continued to use video on an ad hoc basis, most often as part of his performance recordings. But going beyond the simple function of recording, his use of video as a medium is defined by a theatrical dimension. Indeed, with Copers, the video resembles a scene. Copers uses this “other” creative space to shift and materialize his idea of art in time. This questioning of art and creation is achieved through irony or jokes, which aim to awaken and liberate the viewer’s consciousness.

[1] Francis played an active part in the development of video art in Belgium. In 1973, he participated in the launch of the “Continental Film-en Video-toer” by the collective Artworker Foundation. In an attempt to facilitate contacts between the public, film, and video, the artists of the collective equipped a bus with broadcasting equipment and traveled to various cities in Belgium and the Netherlands, the first being Antwerp, where the bus parked in front of the ICC. Francis also directed several Super 8 movies. He was interested in video and recorded a series of experiments involving domino effect. In 1975, he presented one of them, Climax for Tumbling Woodblocks, at the Neue Galerie, alongside drawings and videos documenting previous experiments.

[2] Thereafter, incandescent lamps and fluorescent tubes became constant components of Copers’s work.

[3] Parcours d’eau, May 1 to November 12, 2017, an open-air temporary exhibition at the Château de Seneffe in Belgium.