Marcel Schumacher on

Klaus vom Bruch

Klaus vom Bruch is one of the pioneers of video art in Germany. While staying in the US in 1975 and 1976, the artist—born in Cologne in 1952—begins to explore the new medium of video. Together with Ulrike Rosenbach, he gets to know the video art scene in California. He studies under John Baldessari at the California Institute of Arts in Valencia for a year and is inspired by alternative groups like Guerilla TV. Artists and political protest movements in the US use the television and small mobile video cameras not just to experiment with various media but also politically. As everyday life increasingly comes under the influence of media, or “media America,” as they call it, they respond with self-empowerment, setting up independent stations or television joints. These formats are meant to enable the viewer to determine how to utilize the new media and obtain information unfiltered by economic and power political interests.

Back in Germany, Klaus vom Bruch begins to use videotapes to expose precisely these interests. He works with video for almost a decade and develop his own artistic vocabulary with the medium. In Cologne he founds together with Ulrike Rosenbach and Marcel Odenbach a video label called “ATV – Alternative Television, Cologne, originating after thousands of hours in front of European and American television,” as they later described it in a catalogue of the Kölnischer Kunstverein.[1]

In their atelier at Venloer Strasse 21, a former textile factory, Rosenbach and vom Bruch set up a production studio. They pool their technical equipment: a color camera and a Portapack, a combination of a handheld black-and-white camera and transportable recording device.[2] An editing unit is added later; it will become a decisive factor in the video works by Klaus vom Bruch until around 1986.

These short videos are montages of found footage and their own dramatized scenes. Characteristic is rapid cutting, with short sequences and frequent repetitions which on both the visual and audio levels generate a musical, rhythmical effect. Vom Bruch wrote scores featuring these repetitions for the videos. At this stage of video technology, each repetition is still based on a videotape copy; the loops so common today were thus very expensive and involved to produce at the time. The artist had observed how others worked with found footage while in California. Through this material he brought the media reality of television to video art. At the same time, this enabled him to avoid making the videotapes seem technically backwards in comparison to the television productions. His videos were in color, whereas most of his contemporaries were using black-and-white. From the outset he was able to exhaust the possibilities of the tiny studio by drawing on a number of tricks: he first filmed a mechanical apparatus for the ATV logo, and later he filmed a computer screen (1980) for the opening and closing credits. With public broadcasters initially showing no interest in the new art direction, his videos were shown at atelier screenings or the Galerie Oppenheim on TV monitors.

Ulrike Rosenbach and Klaus vom Bruch, Performance – ein Grenzbereich, 1978, video stills © Klaus vom Bruch, Ulrike Rosenbach, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

In 1978 a number of larger forums emerge at once: ATV takes part in the video colloquium held at Aachen’s Neue Galerie, which was initiated by Dr. Hans Backes and Dr. Wolfgang Becker. There Klaus vom Bruch, Ulrike Rosenbach, and Marcel Odenbach, among others, present the idea of a video hotel where users can not only watch video art in the rooms but also actively take part in the artistic work through a feedback channel. Shortly after, the group participates in the Feldforschung exhibition curated by Wulf Herzogenrath at the Kölnischer Kunstverein.[3] Still in the same year, at the Neue Galerie – Sammlung Ludwig, Klaus vom Bruch hosts together with Ulrike Rosenbach the symposium Performance – ein Grenzbereich. Here performance is explicated as a threshold phenomenon, operating in a liminal space between art, theatre, music, dance, film, painting, and sculpture. Vom Bruch’s videotapes contrast starkly with video productions of this time—instead of placing the filmic medium in the service of the performance or action, he works with the visual material of the “media complex.”

In 1986 Klaus vom Bruch abandons the series of videotapes and turns to installations. In 1992 he takes up teaching, first at the Hochschule für Gestaltung in Karlsruhe (Karlsruhe University of Arts and Design) and then at the Akademie der Bildenden Künste (Academy of Fine Arts) in Munich, where he is appointed professor for media art in 1999.

Moderne Zeiten. Eine autobiographische Analyse, 1978, video stills © Klaus vom Bruch, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Moderne Zeiten. Eine autobiographische Analyse, 1978

The video Moderne Zeiten might seem surprising as an official contribution to the International Year of the Child. Klaus vom Bruch created it in 1978 as part of a research project commissioned by the Federal Ministry for Families. The artist put together a dynamic montage of child advertising material broadcast on the public television stations ARD and ZDF. Scores of laughing, wide-eyed, happy children dash through the video frame. Through editing, the artist synchronized their movements and actions to fit continuous film music. As in a classical silent movie, one hears a glissando in the music whenever one of the children slips. Now and again more gloomy, dramatic passages in the music disturb the overall idyllic impression. The film music was not written for an advertising film but for Charlie Chaplin’s cinematic work Modern Times. Klaus vom Bruch also framed his video with clips lifted from Chaplin’s film. In Modern Times industrial workers on the production line are exploited until they go mad—the flipside of the wonderful world of consumer goods. But the always happy ad-kids are also caught in the perpetual repetition of chocolate bars, toothpaste, toys, and Barbie dolls. Like Chaplin’s tramp, they seem to be thrashing around in a machine. At the same time, Klaus vom Bruch calls the video an “autobiographical analysis,” although nothing from a private home movie was montaged in. The artist does not exclude himself from the fascination with the “idiot box.” Vom Bruch belongs to one of the first generations of children who grew up with daily television commercials—and sought to digest and assimilate this television education.

Schmetterlingsrakete, 1978, video stills © Klaus vom Bruch, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Schmetterlingsrakete, 1978/70, from the series Warum wir Männer die Technik so lieben

Klaus vom Bruch produced several videos exploring gender roles, which—despite the women’s liberation movement—were still firmly entrenched. One series was Die Harten und die Weichen (The Hard and the Soft), another Warum wir Männer die Technik so lieben (Why we men love technology so much).

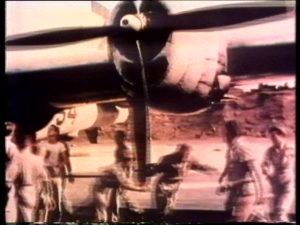

In this video montage, vom Bruch juxtaposes film footage of the testing of the so-called Vergeltungsrakete (“retribution rocket”), the V2 produced by the Nazis, with sequences taken from television documentaries on the lives of butterflies. Accompanied by the well-known voice of Bernhard Grzimek, butterflies are shown hatching, flying, courting, and mating. The artist intersperses quotes:

“But there were times when tyrants ruled the earth / and helped themselves to the women they desired / The boy left / he fancied the daughter / He was 280 years old and produced a boy who was a spitting image.” Towards the end of the video the quotes recall the Bible: “He lived to be 180 and produced 200 sons,” before concretely referring to Genesis: “And he saw that it was good.” Another shot of a dancing butterfly is then followed by the first successful launch of a V2 rocket. The main designer of this “miracle weapon,” Wernher von Braun, was still actively contributing to the rocket programs of NASA in the 1960s despite his involvement in war crimes. Klaus vom Bruch thus turns the motif of the tape into something dubious, out of which his own statement follows at the end of the video: “I don’t want to beget a son.”

Propellertape, 1979, video stills © Klaus vom Bruch, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Propellertape, 1979

This video is also from the series Why we men love technology so much, which looked at the Second World War. Contrasting film images of an American B-17 bomber with a self-portrait of the “artist as a young hero,” vom Bruch shows up the soldierly ethos underpinning the “old” image of masculinity. The bomber in the video does not take off into the sky; instead, soldiers try to push-start the propeller again and again, only for it to fail to gain sufficient momentum. The way the video is cut creates an absurd moment. But what is the bomber’s designated target destination? At the very beginning, the face of a Japanese woman flashes up, the video alluding to the historical context of the dropping of the atom bomb.

Der Geisterseher, 1979, video stills © Klaus vom Bruch, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Der Geisterseher, 1979

The film shots of Allied leaders at the crucial Yalta Conference in 1945 are well known. The video’s title allows the viewer to slip into the role of the “ghost seer” to Winston Churchill, Franklin D. Roosevelt, and Josef Stalin. The war against Germany and Japan was won, the rivalry among the Allies about to get underway in earnest. Shortly after, the Americans dropped the first atom bomb on Japan, literally turning people into ghosts in a split second. The Cold War between the US and the Soviet Union began, ushering in an arms race among states with nuclear capabilities. The famous mushroom cloud of a bomb test in the desert of New Mexico goes off again and again in a rhythmical loop, accompanied by the dance-like score from Charlie Chaplin’s City Lights.

Das Fijiband, 1979, video stills © Klaus vom Bruch, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Klaus vom Bruch and Ulrike Rosenbach, Das Fijiband, 1979

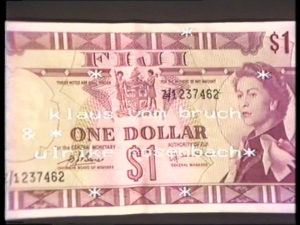

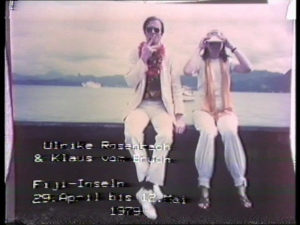

Das Fijiband is unique. It seems like the video of a private vacation; there are no rhythmical loops, nor is there any found footage. As in many videos, however, the sound is the guiding thread, in this case the recording of a radio program on music from the Fiji Islands. Here the artist reworks film footage shot while spending time in Fiji with Ulrike Rosenbach. The Super 8 film shows the classic vacation impressions associated with a tropical island: palms, surf breaking on the beach, coral reefs. The motif on the Fijian dollar bill shows the South Seas as Europeans imagine it and the tourism market desires. In 1979 such trips to the South Pacific by airplane were still relatively new and only just becoming affordable. The video concludes with shots of the return journey, the view from the plane window, of clouds, and landing back in Germany.

Das Duracellband, 1980, video stills © Klaus vom Bruch, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Das Duracellband, 1980

The video opens with aerial shots of a destroyed city, followed by children marching across a school quadrangle, and finally the billowing mushroom cloud of an atomic detonation. Sequences of an advertisement for Duracell batteries are then repeated in a loop: a sliced-open battery that claps back together with a bang. The bang is repeated again and again; the editorial cutting turns it into a rhythmical sound that seems to be then played by the drumming pink Duracell bunny. The interspersed film shots show the dropping of the atom bomb on the Japanese city of Nagasaki in 1945, children with severe burns, and over and over again the cockpit of a bomber. Here, too, the head of the artist features as a counterpart to the bomber pilot, this time as an androgynous figure with long loose hair who tries to hide his face—whether from the blinding light or the gaze of the viewer remains open.

Das Softyband, 1979, video stills © Klaus vom Bruch, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Das Softyband, 1980

Spliced into the loop of a Zewa Soft advertisement for flying, airily soft tissues are images taken from a propaganda film about a bomber pilot who is wearing a leather aviator cap. As the loop continues, the kitschy sweet advertising tune, sung by a young girl, unfurls a tyrannical impact: “Heavenly smooth Softis in your tissue box, take Softis day for day” to the melody of the children’s song “Catch a falling star and put it in your pocket.” Here the image of the virile pilot is contrasted with the fade-in of an ironic portrait of Klaus vom Bruch with long hair blowing in the wind. In the series The Hard and the Soft, Klaus vom Bruch explored themes associated with traditional gender roles. In the 1970s, society was still demanding soldierly steeliness and discipline as the qualities befitting a man, while the men of the hippie movement had rebelled against this with long hair and brightly colored clothes. Ten years later, men with long hair were still being stopped on the street by police. The pilots in the video are not flying American bombers, however. In the closing credits the artist mentions that these were the bombers Adolf Hitler sent to the Spanish putschist Francisco Franco in 1936 to destroy cities like Guernica.

[1] Wulf Herzogenrath, ed., Feldforschung, Cologne 1978, p. 6.

[2] For instructions on how to use it, they consult Independent Video by Ken Marsh.

[3] Wulf Herzogenrath, ed., Feldforschung, Cologne 1978, p. 6.