Barbara London on

Hakudo Kobayashi

When the first portable video equipment reached the consumer market in Japan during the mid-1960s, artists were drawn to experiment with it. Their formal approach was generally influenced by the techniques of avant-garde film, in particular the work of Peter Kubelka and Michael Snow, who visited Tokyo during that time.

The history of video in Japan begins with a 1968 event called “Say Something Now, I’m Looking for Something to Say,” organized in Tokyo by the critic Yoshiaki Tono with the artist Katsuhiro Yamaguchi. Yamaguchi, long interested in new media, in the early 1950s covered his paintings with lenses that turned them into refracted images that shifted as the viewer moved. He applied the same treatment to video monitors. Then in 1969, the “Cross Talk Intermedia Festival” took place at Tokyo Yoyogi Stadium. American electronic composers David Tudor and Robert Ashley performed along with filmmakers Stan Vanderbeek and Toshio Matsumoto. The same year, Rikuro Miyai experimented with multiple television sets in an intermedia presentation, and Taka Iimura made Man and Woman, in which the front and back of a naked couple were shown through two video monitors. Iimura’s video performances analyzed the relationships between subject and viewer, and between live and recorded action. The first international exhibition to feature video installations was the 10th Tokyo Biennale, with the theme “Between Man and Matter,” organized by the art critic Yusuke Nakahara in 1970.

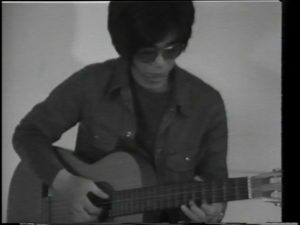

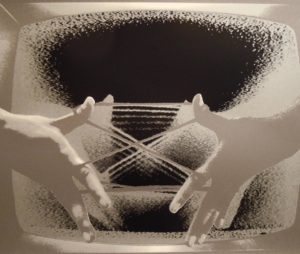

Video Play / Catch Video (by Salvator Tali), 1975, video stills © Hakudo Kobayashi

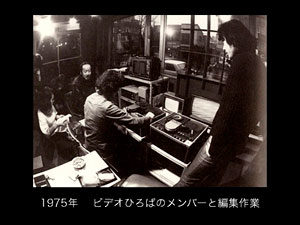

Video production was sparse until 1972, when the Canadian videomaker Michael Goldberg spent four months in Japan. He had arrived seeking contacts for his International Video Exchange Society’s directory. (The Vancouver-based group believed that by setting up a global network of communication between artists and communities, they could counter the centralized mass media monopoly of broadcast television.) Despite the fact that Japan exported the latest consumer electronics, Goldberg discovered a void on the world video art map—not one artist owned video gear. He switched hats from information gatherer to transmitter, and held his “Video Communication Do It Yourself Kit” workshop-exhibition at the newly built Sony Building in Ginza. Many of the local artists involved in the show joined together and formed the group Video Hiroba.[1] They came to video from painting, sculpture, experimental theater, and cinema, as well as from music, photography, and graphics. Many of these early experimenters were “disenfranchised” artists—dissident art students, including many women.

Members of Video Hiroba among them Hakudo Kobayashi (right) and Katsuhiro Yamaguchi (left), 1975; “Video Communication Do It Yourself Kit” workshop-exhibition at the newly built Sony Building in Ginza, 1972

A few members of Video Hiroba, including Yamaguchi and Tono, Hakudo Kobayashi, Fujiko Nakaya, Nobuhiro Kawanaka, and Keigo Yamamoto, jointly purchased a black-and-white consumer video camera. They began exploring the technical limits of the medium and assisted with each other’s projects, which ranged from formalistic videos to social-documentaries. An example of formalist video is the work of both Kobayashi and Yamamoto, who each attempted to use the medium to express the Japanese concepts of ma (the interval or space between people and objects) and ki (the energy that emanates from the spirit.) They presented contrasts of real and depicted space and objects; they also created installations suggesting, by means of feedback and visual interference, the electric “aura” of video equipment. Around the same time, Fujiko Nakaya’s Friends of Minamata Victims (1972), a record of a sit-in protesting a Japanese factory’s negligent disposal of mercury and the ensuing poisoning of the residents of a town, became part of the protest it documented.

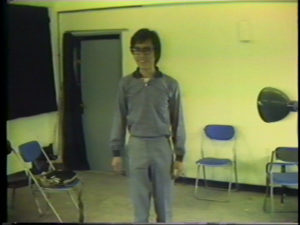

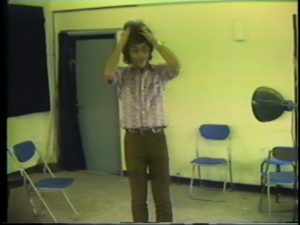

Catch Video (by Watanabe), performed by Masayasu Watanabe, 1975, video stills © Hakudo Kobayashi

In the mid-1970s, members of Video Hiroba engaged in important cross-cultural exchanges. In 1973, Hiroba videos were shown at a conference in Vancouver, B.C. The group received encouragement from New York documentarians John Reilly and Rudi Stern, who lectured at the Tokyo American Center. In 1974, the “Tokyo–New York Video Express” presented the work of thirty American artists along with that of fifteen Hiroba members at a hall in Tokyo.

Around this time, I rode the cresting wave of video art as hardware advanced. The medium’s pliability galvanized a budding MoMA curator like me. Over a coffee, my community of artists engaging with video shared news about what they had just seen, outlined new plans, and answered technical questions. My network expanded beyond Manhattan, as I sat down with practitioners visiting from abroad. Mornings started to feel like Christmas, as a gigantic stack of incoming mail would land on my desk. I would tear open envelopes and read the artist-designed posters, flyers, and postcards, which exuded the same energy as the unruly events they announced. I cross-referenced the flyers’ mishmash of information with the alternative press—the Village Voice, Soho Weekly News, and East Village Eye, and clipped reviews. The listings and articles highlighted only a fraction of what was going on, governed by an editor or an author’s taste or political agenda.

I saved every shred of paper an artist sent me. The incongruent documents were essential for research, given that catalogues were few and far between. The ephemera made its way into file folders that I assiduously organized alphabetically. When young artists asked how to get a show at MoMA, I explained that the process was slow and began with their name on a file folder.

Hakudo Kobayashi reporting, 1978

Friends teaching at Columbia University, NYU, Hunter College, and the Free University in Berlin recommended their best students. Every semester I invited one to be my intern.[2] Their main task was to file the accumulating ephemera in a system arranged either by artist or by organization. They clipped and we saved articles about technological advances, adding subject categories to the system.

After a few years, the file drawers had expanded from four to over forty, and presto we had a Video Study Center. A miniature version of MoMA’s Film Study Center, we were open by appointment to graduate students and scholars who flew in to research video by independent makers.[3]

Video blossomed as tools improved and interest grew. Nationalism contributed to recognition of the new field. The British Arts Council, the Alliance Française, and the Goethe Institute seriously supported their contemporary art and artists featured abroad. I quickly learned that Japan (and India) did things differently. In 1978, Rand Castile, founding director of the Japan Society,[4] invited me to travel and conduct research for an exhibition on Japanese video that would be part of the pan-New York “Japan Now” event series. Such celebratory events crop up regularly, bankrolled by industry to promote their products at department stores and convention centers, and simultaneously put Noh into theaters and visual art into museums.

Lapse Communication (by Tama Art School), 1975, video stills © Hakudo Kobayashi

I was ready, having picked up information about experimental activity in Japan through local events. Shigeko Kubota introduced New Yorkers to Tokyo-based videomakers featured in the “Women’s Video Festival” at the Kitchen. Bill Viola had just returned from Japan galvanized by the culture and artists he met while participating in the Tokyo meeting of Jorge Glusberg’s CAYC (Argentinean Centro de Arte y Comunicación) in 1976. Inspired, I ate my first sushi, read Tales of Genji, and attended every possible Kurosawa film screening and every exhibition held at the Japan Society.

Matsushita awarded MoMA $5,000. With an exchange rate of 400 yen to a dollar, I went over, stayed several weeks, returned and organized the exhibition “Video from Tokyo to Fukui and Kyoto,” and produced a catalogue. Right before my departure, Nam June Paik asked me to carry an announcement card bearing the portrait of Fluxus art founder George Maciunas, who had recently passed away. Paik explained that Maciunas’s connections to Japan dated back more than a decade—in particular to Yoko Ono and Shigeko Kubota, whom he had designated vice chairman of the Fluxus Organization in 1964—but that he had never visited the country. I diligently placed the card in my notebook, thinking about how both Paik and Maciunas were artist-ambassadors and how their actions advanced dialogue between East and West.

Paik contextualized Japanese video for me, describing the multi-cultural and inter-disciplinary bonds that had been cemented in the 1960s through activities at Tokyo’s Sogetsu Kaikan, where the best and brightest of Japan, and quite a few from the rest of the world, met. Founded by the venerable ikebana (flower arrangement) school family of filmmaker Hiroshi Teshigahara, this was the clued-in art center where French New Wave Cinema first reached Japan. Sogetsu sponsored many new music events, such as John Cage and David Tudor’s first performance in Japan, where Paik (in Tokyo to build his first video synthesizer with Shuya Abe) and Ono met in the aisles. Cage, Paik, and Kubota were then forever connected to members of Group Ongaku. Founded by Takehisa Kosugi and Yasunao Tone in 1960, Group Ongaku is essential to the fabric of the postwar Japanese music and interdisciplinary art scene. (Tone later moved to New York, and Kosugi went on to compose for the Cunningham Dance Company.)

Earth, 1974, video stills © Hakudo Kobayashi

Once in Tokyo, I set off immediately for Harajuku—site of the 1964 Olympics, where the city had rebuilt itself with a French-style boulevard and a futuristic stadium designed by Kenzo Tange. The fog sculptor Fujiko Nakaya hosted a dinner for me in her home.[5] That night I met a disparate group of fifteen artists, who had all turned to video from other mediums—experimental film, music, sculpture, printmaking, and computer graphics. They were finding their own way against a staunchly entrenched, hierarchical society. The majority of my dining companions in Nakaya’s home were the founders of Video Hiroba.

I spent days screening work both at the experimental film center Image Forum and in Nakaya’s office, which in 1980 became Video Gallery Scan. The two organizations promoted international exchange and forged a future for media art in Japan. A more local group that I visited, the Video Information Center, was a storefront equipment rental service founded by four art students[6] who painstakingly went about recording the ephemeral actions of Butoh artist Tatsumi Hijikata and Butoh-inspired performer Min Tanaka, among others. The resulting videos now figure as important documentary material.

While Tokyo is the cultural center of Japan, on that initial trip I also went to Kansai, the area embracing the cities of Osaka, Kobe, Nara, and Kyoto, where locals are known for their sense of humor. Kansai art students tend to be idiosyncratic, and they thrive on experimentation. Through the image-processed videos of artist Toshio Matsumoto, I saw how Japanese artists tended to approach the two-dimensional subtleties of the TV screen, treating each frame as a separate composition. This organizational method corresponded, I hypothesized, to traditional artists’ handling of brush and ink, adapting to the season or poem and the confines of the page. Later, over dinner, Donald Ritchie, the American-born, Tokyo-based author who wrote extensively about the Japanese people and Japanese cinema, confirmed this suspicion by characterizing Akira Kurosawa’s and Mikio Naruse’s composing of a single film frame in the same way.

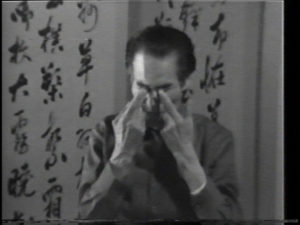

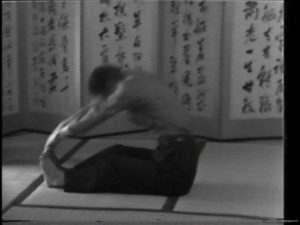

Jikyo Jyutu, 1975, video stills © Hakudo Kobayashi

Most early video in Japan (as elsewhere) began with practitioners taking a modernist stance, analyzing video’s inherent properties. Artists’ work in the 1970s tended to be straightforward, consisting of real-life events fragmented or abstracted into sequences of moments, or as perceptual dislocations.

On that first trip, I noticed that in Japan the first comment about a work is often “Oh, how well it is made,” emphasizing craft. In the West, our first words are more frequently “how interesting,” highlighting content. I perceived another distinct characteristic. I saw how Japanese artists would wait until they could get their hands on (or afford) the authentic gizmo. In North America, with its pioneer spirit, when artists are unable to gain access to a particular piece of equipment, they immediately jerry-rig it (often tinkering alone in the garage or studio).

My research resulted in the survey exhibition “Video from Tokyo to Fukui and Kyoto,” presented at MoMA in 1979.[7] Attracting considerable interest, the show went on to twelve other museums in the United States, Canada, Europe, and in Japan under the auspices of the Museum’s International Program.

Hakudo Kobayashi, Aqua Waves, 1975, silk screen print, Ayatori A, 1975, silk screen print, Ayatori B, 1975, silk screen print

The launch of video art in Japan ostensibly began with the introduction of portable cameras and recording decks in the late 1960s. The timing was right, since the appearance of this new equipment coincided with a new orientation in contemporary art, as many artists increasingly favored concept and process over objecthood and marketability. With its sense of immediacy and relative accessibility, video was adopted by the underground as an art medium and went on to exert a strong influence on other contemporary art practices. Time, moving image, and sound became pliable materials; concerts morphed into open-ended environmental installations.

In looking back at this period, one sees how early videomakers in Japan operated in a twilight zone between the fine arts and the commercial world, a zone in which they had enormous freedom; however, their work lacked the prestige afforded conventional art objects and mass-entertainment products. Still, video made in Japan during the 1970s is filled with ideas. The early pioneers, such as Hakudo Kobayashi, inventively found their way, often gaining access to tools at the schools where they taught. Their work set the stage for the do-it-yourself spirit of gamers, hackers, and web designers.

While the startup phases of new technologies trigger excitement and innovative experimentations, as artists gain control over tools they move on to a dialogue with content rather than hardware. Kobayashi emerged at a fertile moment of the 1970s, when he and a group of distinguished artists paved the way for subsequent boundary-breaking practices and another generation of ideas expressed through media. Like Kobayashi, many of the instigators are still active in Japan today. Since 1979, Kobayashi has worked with the Tokyo Video Festival, a competition sponsored by Victor Electronics. As a writer and an artist, he has endeavored to promote video in daily life through community activities in Kunitachi City, on the outskirts of Tokyo.

[1] The word “hiroba” means public square, and was chosen to imply public communication or thoroughfare. The original Hiroba members included: Sakumi Hagiwara, Nobuhiro Kawanaka, Hakudo Kobayashi, Masao Kamura, Toshio Matsumoto, Shoko Matsushita, Rikuro Miyai, Michitaka Nakahara, Fujiko Nakaya, Yoshiaki Tono, Katsuhiro Yamaguchi, and Keigo Yamamoto.

[2] Over the years my interns went on to become curators, writers, and museum directors, which made me proud. Yet I was sorry if one of the early venues closed, superseded or left behind in changing times.

[3] The Video Study Center operated until 1990. Considered primary reference materials, the documents eventually moved over to the MoMA Library and are used by scholars working on video’s early history. Given the transitory nature of artists and alternative spaces, the documents convey a full story of video art’s history.

[4] Castile served as Japan Society director from 1971–85. He understood that contemporary art curators needed to understand what is happening culturally and socially in Japan.

[5] In 1970, Nakaya had worked with Experiments in Art and Technology (EAT) on the EXPO 70 Pepsi Pavilion in Osaka. She maintained her connection to EAT founders engineer Billy Klüver and artist Robert Rauschenberg for years.

[6] Founding Video Information Center artists included Yusuke Ito, Yasuhiko Suga, Takashi Noyama, and Ichiro Tezuka.

[7] The catalogue included essays by me and Fujiko Nakaya, along with stills of each video photographed by me. The research, exhibition, and catalogue were all realized though the initial Matsushita grant of $5,000, difficult to fathom today.