Renate Puvogel on

Franz Buchholz

The first video sculpture, Entscheidung (Decision) from 1977, draws the viewer in almost instantly into a sequence of disconcerting images of embryos. They are shown along a picture tube, from which a long red cable leads down into a black box. It is an old television set; Franz Buchholz has removed the tube and then connected the two elements. Freed from its chassis, the picture tube is now exposed, as it were, representing the motif directly. The photos of the embryos are from the Aachen University Medical Center. Buchholz used a pan shot to give them the appearance of being in motion and spliced them together into a film. The picture tube, cable, and the box are metaphors for the womb where an embryo develops. The cable is the umbilical cord and supplies the unborn with nourishment, which is here the electronics safeguarded in the box.

This early work shows that, as an artist, the electronics technician is as skillful as he is carefree when using whatever technology is available. Unorthodox down to the present day, Buchholz has experimented equally with technical instruments and artistic media. Building on his extensive knowledge of electronics, he creates for his objects electronic circuits and cabinets, joining them together with unconventional artistic materials.

Buchholz, born in Aachen in 1937, grew up in a family interested in the arts. At an early age he began to express himself creatively while pursuing his career in electrical engineering. After a time working at the Institut für Plasmaphysik (Institute for Plasma Physics) in Jülich, in 1963 he was appointed head of the Electronics Workshop at the newly founded Institut für Technische Akustik (Institute for Technical Acoustics); he completed his first pictures, silkscreens, and collages the same year. In 1968 he began broadening his repertoire to include metal collages, stainless steel sculptures, and electrical objects. This led to the decision in the early 1970s to forge ahead in a new artistic direction, one that would enable him to productively draw on his knowledge of material science, physics, and electrical engineering. Soon after he thus integrated acoustics into his artistic work and, inspired for example by the Zero group, turned his attention to experiments with kinetics, light, and sound. Ultimately, his art is played out in four categories: sound, light—including laser beams, and kinetics, which are then joined by video technology as the main medium in 1975.

Exhibition Franz Buchholz – Licht- und Tonkinetische Objekte im Raum, atrium, Aachen, 1978: Installation I: Lichtkinetische Objekte (left), poster of the exhibition (center), Ton- und Lichtobjekte (right), © Franz Buchholz, photo: Anne Gold

All four areas are frequently intertwined. In Radioskop (Radioscope) from 1979, sounds are rendered visible as graphics on the screen of a rebuilt television fitted with a radio inside. The patterns can be changed by striking keys. The aesthetic composition alone combines all the different ways of working: fittings made of glass and metal are positioned on top of or attached onto precisely built, minimalist bodies of black-painted wood, or fitted into them; thus, the latter serve a function rather than merely acting as the base. Besides the video sculpture considered above, this also applies to another video work entitled Objektiv (Lens) (1980): here a television tube hangs free in a metal frame while the electronics are again detached, set in a wooden box together with a hidden video camera. The camera records the movements of the approaching viewer, relaying images which can then be followed on the screen. It is the interaction between viewer and object that increasingly plays a role for Buchholz.

Two further video works belong to the “video sculptures”: in Der neue Gas-TV (The New Gas TV) from 1978, the screen of an old television tipped on its side is transformed into a gas oven; the panfrying of potatoes is simulated over a flickering flame. This humorous version is contrasted by the video sculpture Zerstörung der Medien (Destroying the Media) from 1980, where Buchholz criticizes the programs of the television channels—at that time still small in number—with their films that allegedly brutalize viewers. Beyond this, he is also interested in questioning the very medium of television itself: in the installation a pickaxe is montaged onto a television set. A video shows its dangerous tip on the screen. Blood dripping down from the pick gathers into a puddle filling the picture. This work in particular is to be seen as a reminiscence of the Fluxus performances of the early 1960s. It was almost exclusively German artists who at the time expressly treated the television as an object and pointedly attacked it. Artists like Wolf Vostell, Joseph Beuys, Wolf Kahlen, and Günther Uecker—not to forget the Korean Nam June Paik, who was living in Germany at the time—brutally assaulted the medium of television, physically taking on the instruments they specially created for the purpose, attacking, mistreating, or even burying them (Vostell, 1963).

In 1978, the Neue Galerie – Sammlung Ludwig organized the two-part exhibition Light and Sound: Kinetic Objects, which was held in the Atrium am Elisenbrunnen, a neoclassical-style building that served as an annex of the Neue Galerie in the heart of Aachen. Along with sculptural works made of light bulbs and fluorescent tubes, the first part focused on works with laser beams. The second section was devoted to acoustic works. Memorable and extraordinary was the performance of two dancers on an acoustic dance floor; with each movement they made across the floor, electronically generated sounds were stereophonically audible over loudspeakers.

Buchholz’s first experiments using the screen as a paint surface and creating pictures with color television and video camera go back to 1977. This was a huge step away from familiar territory, for it meant replacing canvas and brush, applying new media instead. Very early on Buchholz succeeds in producing some remarkable works.

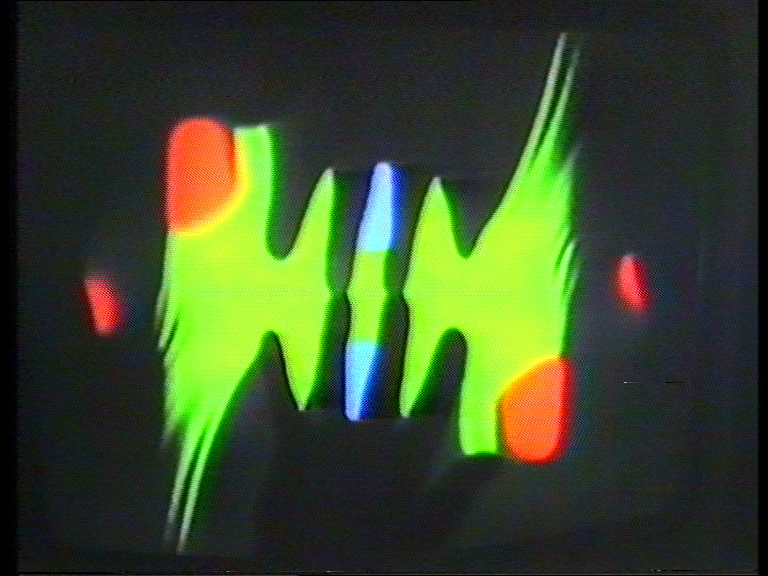

Hands I und Hands II: 1979-1981, video stills © Franz Buchholz

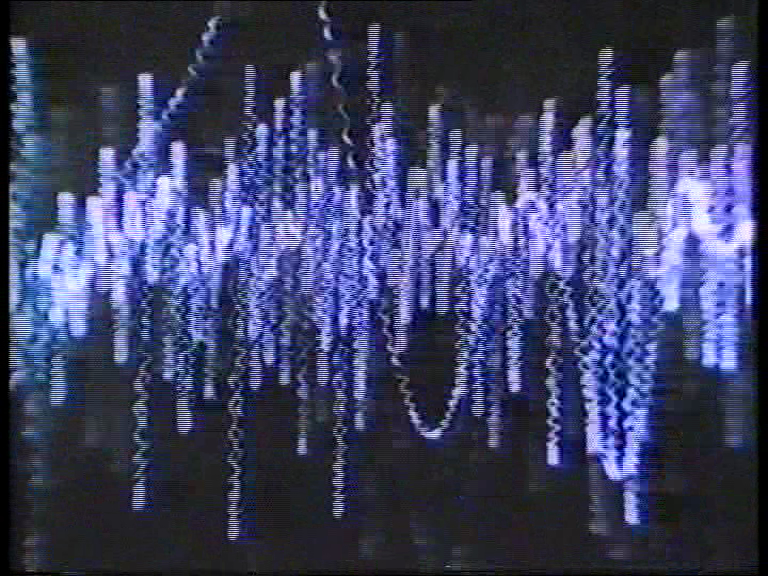

Video Painting, 1977-1981

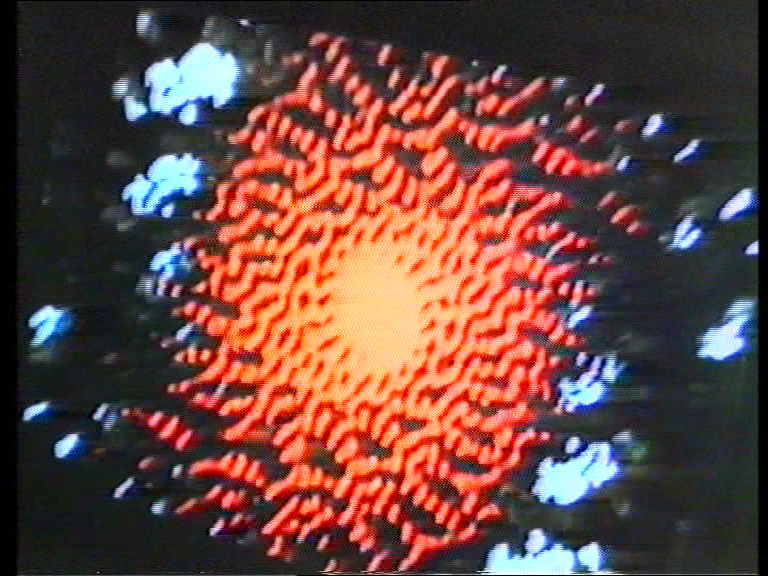

A black felt pen draws simple geometric figures like a triangle, circle, or rhombus directly onto a screen, an electronically functioning painting surface. An upside-down video camera points at the screen and films the color structures and surfaces directly, a connected video recorder stores them: simultaneity between reality and image. Through back coupling—technically produced by connecting the camera to the inlet of the monitor—pictures arise which in color and form change continuously and fluently. With the camera inverted, the pictures appear double, allowing richly complex compositions to gestate around a mobile axis. Indeed, they even overlap in parts and take a seemingly three-dimensional form. A drawn spiral can turn into a spiraling thread. The individual drawn figures generate ever new vibrating, abstract color patterns in tandem with different movement sequences. The distinction between line and surface virtually disappears. With a new motif the drawing hand introduces a new sequence, a caesura that rhythmically animates the series. The latter are created over a number of years in loose succession and brought together later in a video.

Only the early video technology allows these kinds of interventions and manipulations; it requires however the technical skill of an expert and the daring to experiment without the certainty of a specific outcome. With sound compositions running in reverse, recorded together with Frank Castro, these multimedia works, described as “visual audiotapes,”[1] are important contributions to synthetically generated pictorial documents. Ultimately, these experiments go back to the performances of Nam June Paik. Since 1963 the Korean had used magnets and special interferences to distort, manipulate and, as it were, electronically paint video images; together with Shuya Abe, in 1970 Paik developed the first video synthesizer, the anti-gesture par excellence of a Fluxus artist. Fluxus in turn rekindles elements of the Dada movement. It was Hans Richter who, sometimes working with Viking Eggeling, had invented abstract films under completely different conditions in Dada’s birthplace, Zurich, between 1916 and 1918 and employed different means, montaging images and drawings.

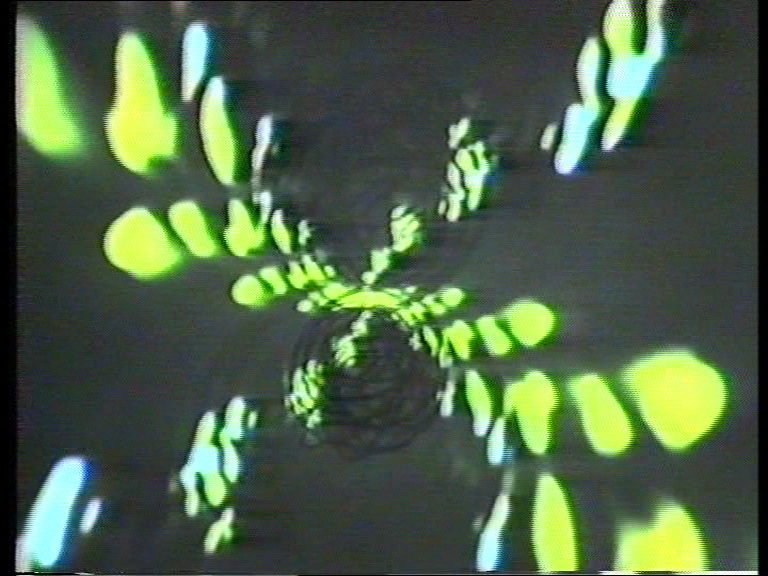

Strukturen I-V, 1981, video stills © Franz Buchholz

Moving Structures and Color – Drawings in Motion, I-V, 1981

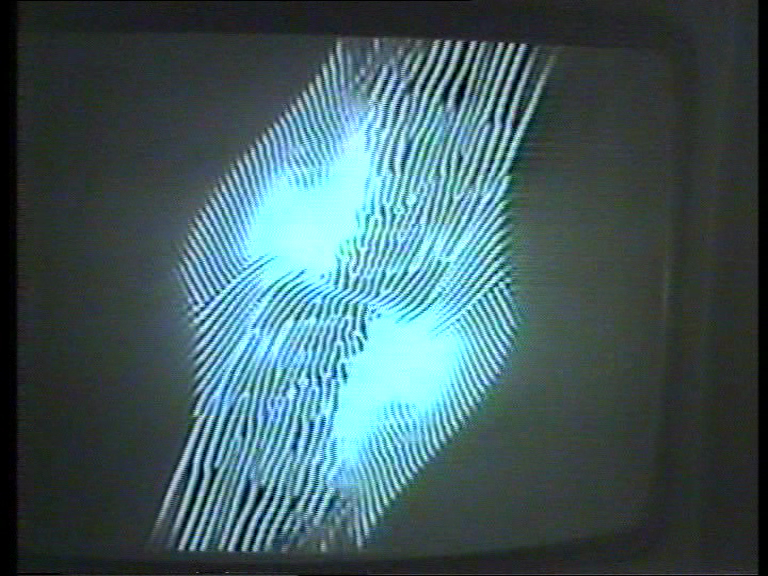

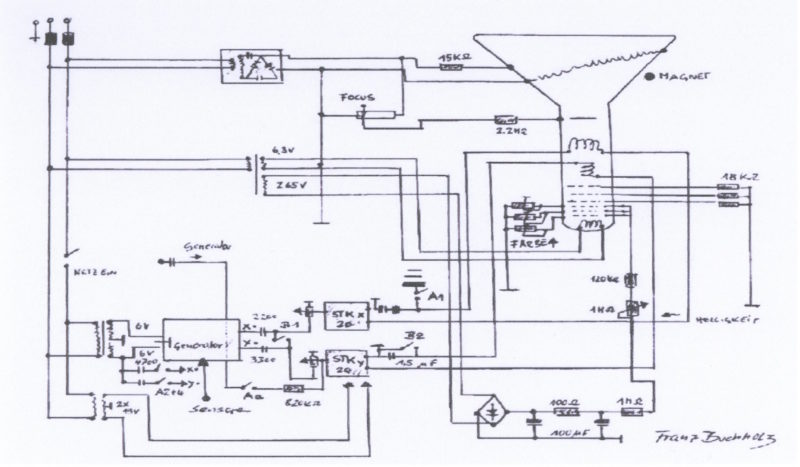

It is not absolutely necessary to have an intermediary like a drawing hand to generate new types of images. Thanks to back coupling, it only takes a video camera focused on a screen to activate gyrating images in the most brilliant colors and imaginative forms and figures. The directional movement of the patterns depends on the gesture made by the filmmaker. Exceptional circular patterns arise when the artist slightly swivels or tips the camera. Against the black backdrop the colors shine all the more intensively. Accompanied by sequences of atonal sounds aligned to the abstract image phases, the videos evoke associations ranging from posters advertising fairs through to celestial phenomena, the viewer’s orientation dissolving in spherical spaces. As always, this work arises out of a mixture of planning (detailed circuit diagrams) and improvisation. In the “flux” of a current, drawings attached to a transparent foil generate visual elements floating in space. Along with Buchholz and Frank Castro, the musical effects are from Ramon Creutzer and T. Wach.

Hands I and II, 1981/82

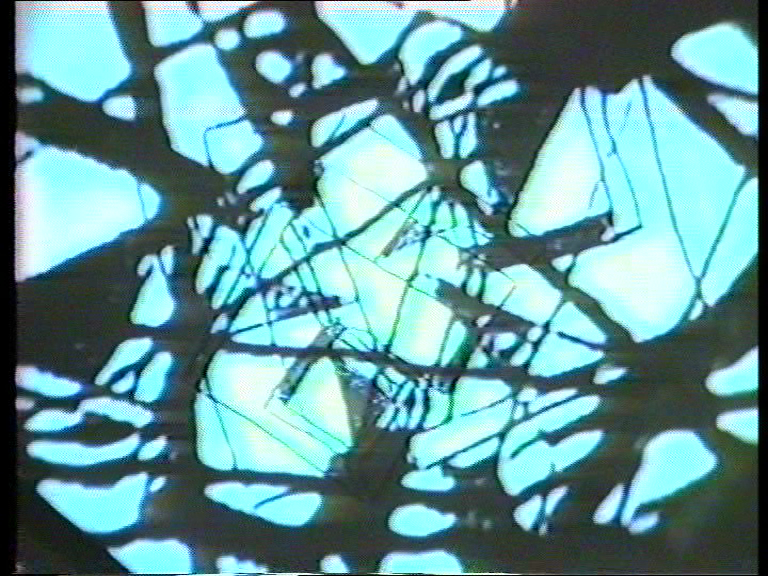

Just something compact shoved between camera and television is all that is needed to fundamentally influence the images. This is observable on videos where Buchholz, holding the camera upside down in his left hand, places his gesticulating right hand in the space between the devices. Doubled, the fingers meet as black silhouettes and between them there opens a rich play of colors. Other changes are generated when the artist steps closer to the screen and occasionally swings the video camera ever so slightly, whereby the early video camera’s noticeable sluggishness shows how the image first has to construct itself. The respective lighting also has a decisive influence; here Buchholz makes do with a focusing lamp. Subtly attuned to the nuances of the changing colors, the sound contributes considerably to the distinctive impression (Buchholz, Castro, Creutzer, Wach).

To generate more attention for young video art around 1980, a store specializing in hi-fi and video equipment in Aachen agreed to show video works by Aachen artists in its shop windows, a project initiated by the film director Wolfgang Becker. As part of the presentation Art and Technology held at the Neue Galerie in 1981, some of the video works by Buchholz described above were shown there.

Franz Buchholz, design drawing for SKOP III, 1992, © Franz Buchholz

As mentioned, only old televisions and video cameras allow the kinds of interventions described above. This means that such a vibrantly alive visual world cannot be generated with the new flat-screen televisions. Nevertheless, Buchholz resourcefully uses developments in electronics. In Skop II from 1989, touching the sensory fields of a converted television reveals black-and-white graphics. Three years later, in Skop III from 1992, the screen of a color television serves as the projection surface for a heaving, wavy sea of bundled color forms. The play of colors is completely different from preceding works, more graphical, constructed namely out of oscillating lines without color fields; its more synthetic, precise, electronically produced character replaces the formerly improvised, ever-changing graphics.

Since the 1990s Buchholz has created large room installations, for instance the elaborate video installation Surveyor from 1998 for the riflemen gangways at the Jülich bridgeheads. Video now serves the artist primarily as a documentation medium. Transferring an object into another medium lends it however a completely different significance, evident for example in the work Laserobjekt (Laser Object) from 2013. Observable in Spiegelobjekt (Mirror Object) from 2016, these works, without casing of some sort and with a visible montage in video, lose their scale. Accompanied by crystalline sounds, they take us to fantastic, spaceless spheres. The components are ultimately very much ordinary everyday things: for the laser object, Buchholz split a laser beam and changed it so that it now transmitted shining red rays wandering aimlessly to and fro. The Spiegelobjekt from 2016 is based on an optical glass body that he glued into a mirrored glass case. Using Magix Video de Luxe, the artist then processed on the computer the mobile play of the color rays generated on the object, creating a video that was recorded on DVD.

To conclude our considerations: the sheer joy in innovative experimentation is something that has not yet deserted the artist.

[1] Wulf Herzogenrath, ed., Videokunst in Deutschland 1963–1982, Baden-Baden 1982, p. 14