Pieter Vermeulen on

Filip Francis

Solo for Tumbling Woodblocks (1975) is a compilation tape with video recordings of actions carried out by Belgian artist Filip Francis. Not only does this piece provide us with unique historical evidence of his site-specific happenings; in many ways it also epitomizes what is at stake in Francis’s oeuvre.

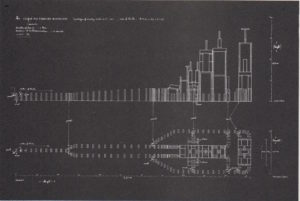

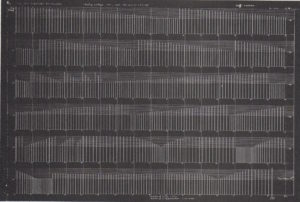

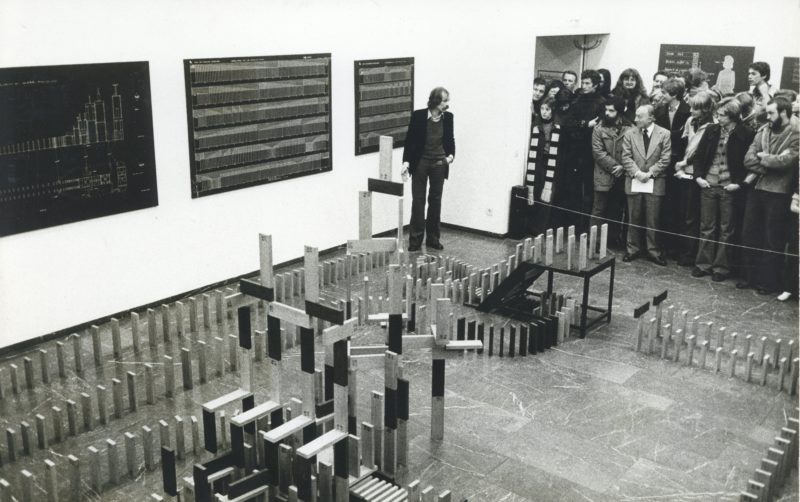

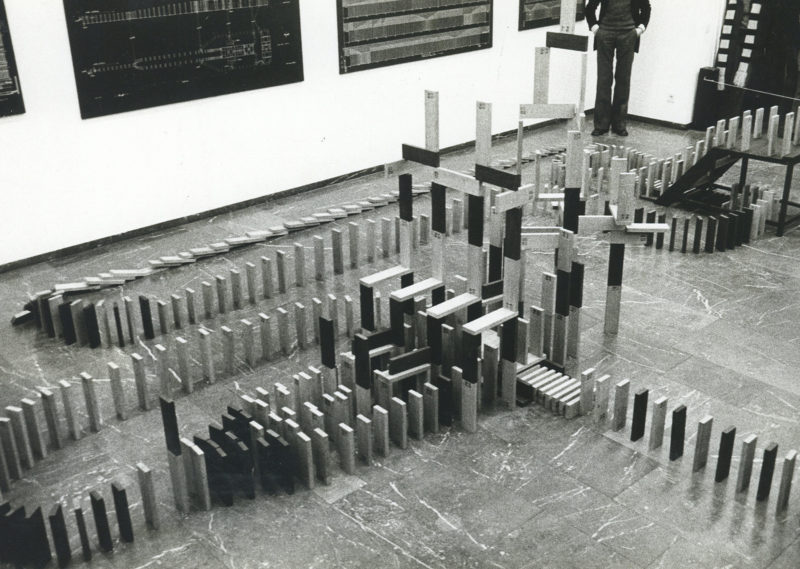

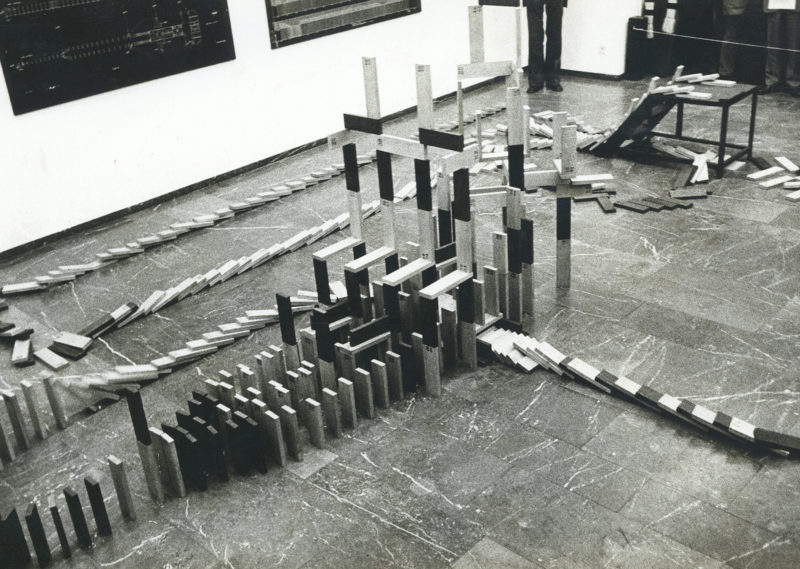

Filip Francis, Climax for Tumbling Woodblocks, November 22, 1975, on the occasion of the exhibition Belgien: Junge Künstler I, Neue Galerie – Sammlung Ludwig, Aachen, November 22 – December 28, 1975, © Filip Francis, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, courtesy Annie Gentils Gallery, Antwerp

Filip Francis was born in 1944 in Duffel, a municipality in the province of Antwerp, Belgium. Aged twenty, he started his art studies at the Hoger Instituut Sint-Lukas in Brussels. This was right around the time when the immensely popular and novel art forms of Happenings and Performances had gained a foothold on the European continent. The young Francis attended several happenings, most notably those by The Living Theatre, by now well known as the oldest experimental theatre group in the United States. Unsurprisingly, the innovative art form would have an undeniable influence on his practice as a visual artist. Meanwhile, and especially in the years 1969–1970, his hometown Antwerp had turned into a trendy hub for contemporary art, following a relatively short period of occupations and protest against the institutional establishment.[1]

Filip Francis, Climax for Tumbling Woodblocks, November 22, 1975, on the occasion of the exhibition Belgien: Junge Künstler I, Neue Galerie – Sammlung Ludwig, Aachen, November 22 – December 28, 1975, © Filip Francis, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, courtesy Annie Gentils Gallery, Antwerp

Various underground movements, artist collectives, and communes were being founded as a new playground for progressive thought and free expression. One of those initiatives was Filip Francis’s Vacuum voor nieuwe dimensies (Vacuum for New Dimensions), which was established in 1970 together with his wife, Maryse Masson, on the ground floor of a lofty Art Nouveau house, shared with fellow-artist Luc Deleu and his wife. It was located on the majestic Cogels Osylei, often called the most glamorous street in Antwerp. During its mere two years of existence, Vacuum gave birth to a wide-ranging, experimental program of exhibitions, including solo shows by Deleu and Francis, as well as several screenings and happenings. The artist initiative was soon being followed by upcoming Belgian curators such as Jan Hoet and Florent Bex.[2] The self-proclaimed end of Vacuum, in 1971, was partially motivated by Francis’s renewed interest in the further professional development of his own oeuvre.

Filip Francis, Climax for Tumbling Woodblocks, November 22, 1975, on the occasion of the exhibition Belgien: Junge Künstler I, Neue Galerie – Sammlung Ludwig, Aachen, November 22 – December 28, 1975, © Filip Francis, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, courtesy Annie Gentils Gallery, Antwerp

In turn, the rich ecosystem of underground initiatives in Antwerp would prove to be fertile ground for the founding of the ICC (International Cultural Center), an institution that would play a historic role throughout the 1970s and 80s. Established in 1969, the ICC was housed in a former royal palace on the prestigious Meir, Antwerp’s main commercial boulevard. Originally driven by the frustrated desire of local artists for more exposure in a cultural landscape that barely offered those opportunities, it is considered to be the first official contemporary art institute in Belgium. With the appointment, three years later, of Florent Bex as the new director, the ICC truly grew into a beating heart of the neo-avant-garde, and this for well over a decade.[3] Now-prominent artists such as Laurie Anderson and James Lee Byars, who were still emerging at that time, even felt a need to invite themselves for a performance or exhibition. With the acclaimed Wide White Space gallery[4] closing its doors in Antwerp in 1976, all eyes were suddenly focused on ICC, exactly the place where Filip Francis held a solo exhibition in 1977.[5] The artist had always stayed on good terms with Bex,[6] who once characterized him as a “hipster with grand ideas.”[7] Together with his compagnon de route Luc Deleu, digital pioneer Hugo Heyrman, and photographer Bernd Urban,[8] Francis had previously initiated the Continentale Video – en Filmtoer, a mobile cinema showing work by (mostly Belgian) artists and underground filmmakers. The project was launched at ICC on March 31, 1973, to then start its tour through Belgium, Germany, France, and the Netherlands over a period of three months, with an estimated visitor count of 15,000. Their experimental approach is a good illustration of the way in which video art was being perceived and received within the artistic community of the seventies. The swift emergence of consumer video technology had led to an ever-increasing democratization and wider availability of the medium to visual artists. Recording, presenting, and distributing videos had suddenly been made easy and accessible. The international promotion of video art that went with it, however, likewise resulted in a “rather hasty over-fascination”[9] by artists, exhibition makers, and directors in Belgium, whose sudden interest in the technology was often ill-motivated.

Filip Francis, Climax for tumbling woodblocks, prototypes © Filip Francis, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, courtesy Annie Gentils Gallery Antwerp

This being said, ICC managed to build a considerable archive of video art through the years, which is still accessible today.[10] Over eighty percent of the works were produced by Continental Video, a non-profit organization that took its name from the above-mentioned video tour. Founded in 1974 by ICC director Florent Bex, together with Chris Goyvaerts and Kris Eckhardt, Continental Video was the first production agency for video artists in Belgium. Their collaboration gave rise to numerous documentary videos and artists’ tapes, with James Lee Byars – the 100 images are in one second (1976) among the more prominent examples. With virtually no budget and most of the work being voluntary, the acquisition of (expensive) equipment was made possible by ICC’s creative accounting practices.[11] Continental Video also produced Filip Francis’s Solo for Tumbling Woodblocks (1975), a tape containing four different recordings (originally on half-inch open reel tape) of visually similar, site-specific actions performed by the artist.[12] At first sight, the video recordings are mainly to be valued for their documentary character, rather than for a more autonomous, artistic engagement with the medium. Nonetheless, drawing a clear demarcation line between both seems difficult. The low-key approach to the production of these videos often resulted from an intense dialogue between the artist and Continental Video. This is most clearly the case for the recording that was made in the Sint-Anna Tunnel, the pedestrian tunnel connecting the two banks of the River Scheldt in Antwerp. Here, on March 17, 1975, Filip Francis lined up a series of woodblocks over a distance of eighty meters. He then pushed over the first block, causing a chain reaction. While it took the artist over two hours to arrange the wooden pieces, the domino effect lasted a mere 40 seconds. This incommensurate relation between the painstaking arrangement and the swift, playful tumbling down of the blocks makes an oddly comical, even absurd impression on the viewer.[13] In order to be able to follow this rapid movement, Francis decided to mount the camera on a baby carriage that was manually pushed along the line.

Solo for Tumbling Woodblocks, 1975, video stills © Filip Francis, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

The Tumbling Woodblocks protocol, so to speak, was iterated eleven times in the period 1975–1978.[14] Even if each action would vary according to its specific time and place, the underlying scenario remained pretty much the same. After the artist had spent a considerable amount of time setting up the blocks in variable constellations, the audience would see it tumbling down like a house of cards. Important to note, however, is that Francis’s performances and interventions are embedded in a larger conglomerate of audio and video recordings, photographs, paintings, and drawings, often blurring the boundary between the actual work and its documentation. The artist’s deliberate use of and reliance on documentation can be seen as a way to reconfigure the live, temporary, and fleeting nature of the happenings that he was so influenced by. The musical connotation of the word “solo” in the title originates from the fact that each action (and its recording) was equally conceived as a sound composition. The different sizes (18 to 30 cm x 2.2 to 7.5 cm) and wood varieties (oak and wenge wood) of the blocks, normally used for parquet floors, generated a fast-paced acoustic arrangement. The scores would then be notated by the artist in the form of compositional diagrams, which were regularly put on show together with the (performative) installation of woodblocks.[15]

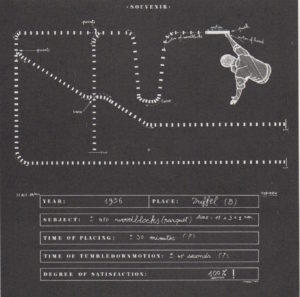

Filip Francis, Souvenir, top and side view, 1975 © Filip Francis, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, courtesy Annie Gentils Gallery Antwerp

This interconnection of the visual and the auditory clearly reflects one of Filip Francis’s key fascinations: the intricate relation between space and time.[16] In fact, the diagrams are reminiscent of a previous series titled Souvenirs (1973–1975), composed of drawings and paintings dealing with his childhood memories. In these series, Francis attempts to give an objective and detailed account of personal experiences encountered in his youth, each of them marked with a specific time and place, as well as their “physical/psychic results” and “degree of satisfaction.” Most of the pieces are rendered in tempera and oil on a green panel, aesthetically similar to a school blackboard. Two of these “souvenirs,” dated 1956, portray the artist at the age of twelve, pushing over the first in a row of 450 woodblocks, composed in a regular pattern. Looking at these works, it becomes clear that these innocent childhood memories actually constitute the ur-scene of what Francis, later on in his life, would repeat countless times with an almost compulsive rigor, dedication, and pertinacity. Or, as the artist himself once described his action, “petite cause, grandes conséquences” (small cause, great consequences).

[1] See Johan Pas, Vacuum voor Nieuwe Dimensies 1970–1971, Antwerp: Galerie Rode Zeven, 2006. Johan Pas’s art historical research has been an indispensable source in understanding the artistic climate of Antwerp during those decades. Most of the ongoing research is publicly disclosed in the following online archive: www.belgiumishappening.net

[2] Jan Hoet would establish the Museum for Contemporary Art in Ghent (currently known as S.M.A.K.) in 1975. Ten years later, Florent Bex became the director of the newly founded Museum of Contemporary Art M HKA in Antwerp.

[3] A full, detailed account of ICC’s history can be found in Johan Pas’s doctoral dissertation: Beeldenstorm in een spiegelzaal: het ICC en de actuele kunst, 1970–1990. Leuven: Lannoocampus, 2005.

[4] The Wide White Space gallery was founded by Anny De Decker and Bernd Lohaus in 1966 and showed work by leading artists such as Joseph Beuys (most notably), Carl Andre, Günther Uecker, Gerhard Richter, and Bruce Nauman, among many others.

[5] The exhibition took place from January 15 to February 27, 1977, and was accompanied by a (now rare) trilingual catalogue (in Dutch, French, and English).

[6] Remarkably, Bex also used to profile himself as an artist under the pseudonym Hubert van Es.

[7] Pas 2006 (see note 1), p. 4.

[8] Together they had been active as members of the Artworker Foundation (ARFO), founded by Heyrman in 1971.

[9] Jan Debbaut, “Some Notes on Video Art in Belgium,” Studio International, no. 982 (May/June 1976), pp. 273–274, here p. 273.

[10] The ICC archives, composed of 600 videotapes, are currently hosted by M HKA in Antwerp.

[11] Interview with Chris Goyvaerts, Antwerp, March 27, 2017.

[12] The recordings are captioned as follows: “1. Solo for Tumbling Woodblocks, 1975, S Annatunnel Antwerpen; 2. Experiments = Crescendo for Tumbling Woodblocks (Failed!); 3. Crescendo for Tumbling Woodblocks (75); 4. Piece for Tumbling Woodblocks at Spectrum Gallery Antwerpen 1975.”

[13] “A marked contrast exists between the erection and the falling over of the woodblocks, and the relative and temporary character of the whole action,” quoted from Florent Bex, “Introduction,” in: Filip Francis, exh. cat., NICC, Antwerp, 1977, pp. 46–48, here p. 48.

[14] More specifically at Palais des Beaux-Arts, Brussel (1974); St. Anna tunnel, Antwerp (1975); Galerie Spectrum, Antwerp (1975); the artist’s studio (1975); Café De Skipper, Antwerp (1975); Vleeshal, Middelburg (1975); Neue Galerie – Sammlung Ludwig, Aachen (1975); ICC, Antwerp (1977); Cultuurcentrum Scharpoord, Knokke-Heist (1977); in Stuttgart; and in De Warande, Turnhout (1978). More recently, the work has been carried out once more on the occasion of the historical exhibition Dear ICC at M HKA in Antwerp (2004–2005).

[15] “Formal data such as type of wood, dimensions, given space, manner of arrangement are structurally analysed and recorded – just like scores – in compositional diagrams, to be executed later as public actions.” Bex 1977 (see note 13), p. 47.

[16] The role of time in the work of art has, among others, been analyzed by Umberto Eco in his essay “Il tempo nell’arte” (On Time in Art), included in his essay collection Sugli specchi e altri saggi, Milano: Bompiani, 1985, p.119. A Dutch translation of the essay was retrieved in Filip Francis’s folder in the ICC archives at M HKA, even containing an image of Francis’s work. Unfortunately, no English translation or further bibliographical reference could be found.