Christine Hill on

Ernest Gusella

The first-generation video artist Ernest Gusella was a painter and musician attracted to the new medium’s capacity to render both image and sound within an interactive studio environment using a vocabulary of waveforms, frequencies, and voltages. Gusella’s Collected Works 1974–78 in the Ludwig Video Archive, Aachen, represent work from a period in the US when a generous approach to sharing technical information among artists along with the user-friendly Portapak and emerging video synthesizers shaped aesthetic aspirations for the new time-based medium.

Gusella, born in Calgary, Canada, in 1941, grew up with eclectic interests, including a serious study of the violin starting at age seven. After attending the University of Idaho to study biochemistry, Gusella moved to the Alberta College of Art, where he started painting. He left western Canada in the mid-1960s for New York, where he took classes at the Art Students League. In 1965 he moved to San Francisco and attended the San Francisco Art Institute, receiving BFA and MFA degrees in painting. In San Francisco, he was exposed to early experiments in video supported by the public television lab at KQED, as well as the integration of video into light shows accompanying live music events.

Ernest Gusella, Japanese Twins and White Man. A Lock and Low Album, 1977 (the sound of the video piece Words is from this record album), The Lone Arranger Writhes Again!, 1980, Zen O’Phobia, 1987, record covers © Ernest Gusella

After returning to New York in 1969, and inspired by Gene Youngblood’s book Expanded Cinema (1970), Gusella purchased a Putney audio synthesizer. In his “Statement on Early Video Works with Oscillators” Gusella noted, “I was constantly frustrated with the inability of that medium [painting] to convey sound.”[1] His early video images, produced during 1971–74, approached this problem by using oscillators to generate audio waveforms that could be displayed visually on an oscilloscope. These abstract images were then modified in various ways by mirrors, prismatic lenses, and other distorting optical devices, and finally recorded on video.

Ernest Gusella, I Will Not Be Kowed, 1990; Dada Raga, 1993; STRUM und TWANG, 2000, record covers © Ernest Gusella

One evening while walking through New York’s West Village, Gusella “heard strange sounds coming out of a church where WBAI, the Pacifica [radio] station was having a fundraiser.” [2] At the event he encountered early video pioneers Woody and Steina Vasulka, who were also working with a Putney synthesizer and other tools developed by artist-friendly engineers. Soon, with support from state arts funding, the Vasulkas would co-found the Kitchen in New York’s Soho district, an early multi-disciplinary artists’ space, described by Woody Vasulka as a “live audience testing laboratory”[3] that welcomed artists who, like Gusella, were experimenting with the video medium.

Ernest Gusella, in dead ernest. his gravest hits, 2002, icicle, my ice cycle, 2003, Hotrod Golgatha, 2003, record covers © Ernest Gusella

Gusella’s video instruments soon expanded to include a Portapak and a VideoLab, a 4-channel video synthesizer developed by Bill Hearn, an important early tool designer working with artists. Both Woody Vasulka and Ernie Gusella have commented on the open cultural terrain that video art represented at this time. In a 1995 interview, Vasulka talked about the early 1970s: “Video was undefined, free territory, no competition, a very free medium. The community was naive, young, strong, cooperative, a welcoming tribe. There was instantly a movement mediated by two influences. One, the portapak, made an international movement possible, and two, the generation of images through alternative means—the camera no longer carried the codes.”[4] Gusella, in a 1979 statement, explained how he found video to be an appropriate instrument for his early audio and visual investigations: “I probably would like to be a formalist, but resent the elitism that a formalist stance requires. Instead I am probably a neo-Romantic—a person who once strongly believed in a certain set of principles, and who, for some reason, stopped believing, and is currently engaged in the process of trying to develop a new set of principles that can be believed in. As a new medium, video is the perfect tool with which to satisfy these particular demands.”[5]

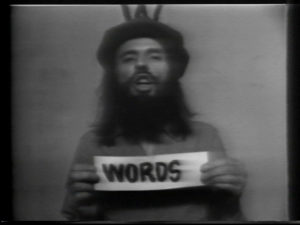

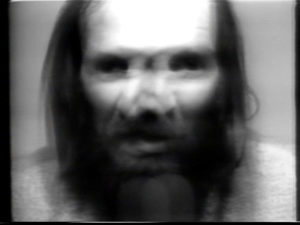

Words, from Collected works, 1974–1978, video stills © Ernest Gusella

Collected Works, 1974–78 finds Gusella working with an electronic toolkit offering luminance keys, wipes, switching, and colorizing, with the capacity to combine multiple cameras and other effects channels, supplemented by various electronic and analogue musical instruments. In this body of work, Gusella clearly looks back to Surrealist poetry and Dadaist humor as well as committing to an exploration of the new medium of video. In all of these tapes, Gusella’s own physicality—tall and angular, long-haired and bearded—is prominently featured as he performs with his multiple camera set-ups that are combined and modified by the patches on the VideoLab. Watching these tapes decades later, Gusella is unmistakable as a caricature of a countercultural “freak,” a heretical hipster. But we also recognize this distinctive image as the artist himself, in his studio, the conductor of cleverly orchestrated performances where, interacting with his array of electronic instruments, he fractures and disorients the viewer’s sense of space. Video curator John Minkowsky pointed out that in Gusella’s confounding image processing experiments, “the collaborator in this game of chance is not human; rather it is the machine … the video system automatically switching between two camera views of the artist performing simple, effective gestures.”[6]

Video-Taping, from Collected works, 1974–1978, video stills © Ernest Gusella

Gusella’s projects from 1974–78 demonstrate a playful yet rigorous sensibility that, in partnership with his machines, performs visual and spatial riddles that are intriguing, entertaining, and often disarmingly elegant. A detailed description of Video-Taping offers insight into the mix of high and low cultural and technical references characteristic of Gusella’s work at this time. Here the word “play” in the title sets up an understated contrast between the sophisticated technology of the VideoLab synthesizer and the medium of tape—not only the iron oxide–coated acetate, the videotape that will record the performance of Gusella and his electronic instruments, but also the common household adhesive tape, which becomes a low-tech yet expressive tool in this project. Gusella’s playful punning in the title is echoed by formal and perceptual contradictions produced in his confounding black-and-white electronic theater. In Video-Taping the viewer initially encounters a silent screen, where the left half of the screen appears white and the right half black. Then Gusella starts peeling off what is quickly recognized as a piece of adhesive tape from the left screen, revealing a high-contrast positive image of himself “behind” what appears to be a taped surface (a piece of glass) placed between Gusella and one of the cameras, a spatial feint. The piece of tape is then placed directly adjacent onto what appears to be the “black” screen on the right. What had appeared as a piece of opaque “white” tape on the left, now appears as a “clear” narrow window on the right, revealing the same Gusella camera image, now in negative. This transformation from an opaque tape layer on the left to a “clear” strip on the right has been accomplished by luminance keying, a process, available by way of the VideoLab, where a specific brightness level can be identified and turned into an electronic stencil through which another image can be channeled. The complexity of Gusella’s composite images begins to be revealed when the viewer recognizes that the illusion of the figure being seen “through” the taped surface on the left is, in fact, another luminance key. In this work two different cameras are used, one on the taped glass surface and one on Gusella.

Pound and Deviated Septum, from Collected works, 1974–1978, video stills © Ernest Gusella

At the midway point in the tape, the screen displays a series of broad bands that alternate opaque black and white strips with a second channel of images—keyed- in positive and negative images of Gusella. This screen with bands of material, while produced with low-tech adhesive tape, also playfully references the electronic horizontal scan lines on an analogue video monitor, or an image generated when certain waveforms and frequencies are fed into the scan mechanism of the monitor, a visual pattern with which Gusella would be familiar (see this banding effect in Pound). When Gusella’s video-taping exercise is complete, with all of the tape transposed from the left to the right side of the screen, an unobstructed positive image of Gusella is seen on the left, paired with his negative image on the right. This elegant puzzle uses multiple inversions, spatial illusions, and word play, a basic vocabulary explored throughout this body of work during this period.

Dude Defending, from Collected works, 1974–1978, video stills © Ernest Gusella

Other projects in Collected Works 1974–78 offer variations on Video-Taping’s multi-channel constructions, the play of black and white linear elements and punning titles. In Dude Defending a Stare-case (a reference to Duchamp’s famous descending nude) two camera images are mixed using a moving horizontal wipe. A distorting lens focused on crossed, striped sticks is used on one channel to create a kind of receding staircase image; the second camera captures Gusella, now in dark shades, brandishing the weapon-like sticks. The soundtrack features the sawing and plucking of a stringed instrument with the occasional menacing musical phrase. A playful reference to vertigo in the title Vere d’he Go Composition announces a more vigorous attempt at spatial disorientation using again the striped sticks and now vertical wipes. Neo-Plastic Key introduces the sticks in a more psychedelic electronic environment that uses undulating wipes and rhythmical guitar strumming. Wolf-Zooming, produced one day after a grant proposal was rejected, again delivers aggressively disorienting perceptual effects. Gusella described this set-up: “I … went to work on my face and teeth, zooming in and out ferociously, using a piece of tape to whip the zoom lens back and forth … Stream of consciousness is where it’s at.”[7]

Video-Wiping, from Collected works, 1974–1978, video stills © Ernest Gusella

Another set of projects uses two cameras and keying to complicate simple physical actions. Heads and Hands reveals an apparently unified physical space with Gusella’s face and hand. Luminance keying is then used to superimpose his hands and face onto each other in a series of silent, elegant illusions, suggesting an early study for Video-Taping. Also related to Video-Taping are Video-Wiping and Portrait. Both make use of a sheet of glass covered with some mundane household material to create an opaque surface onto which Gusella performs simple gestures like drawing that, in combination with keying, play out games of occlusion and revelation.

School and Rash, from Collected works, 1974–1978, video stills © Ernest Gusella

Yet another group of projects in Collected Works 1974–78 features Gusella wearing random words on T-shirts for short absurdist performances. In a 2007 interview, Gusella reflected on his ongoing “interest in abusing language.”[8] These projects, a kind of audio-visual sound poetry with titles like School, Sundae, Pound, Rash, and Blank, offer a range of gestures, from gentle hand movements to more bellicose punching with boxing gloves. The pulsing brightness changes and colorizing appear to be coordinated with the rhythmical jabbing, although, to undermine easy expectations, at the end of School, Gusella stands still while the pulsing continues, now clearly driven by his machine collaborator. Words was described in a review by artist Davidson Gigliotti as a “maniacal children’s program.”[9] In this extended song Gusella treats words, printed on flash cards and pinned to his clothes, as a concrete material element that punctuates, nonsensically, physical and aural spaces. The Dadaist invocations in these short performances are made more explicit in Arrows, as Gusella repeats the sounds of the word “arrows” that eventually morph into “… A.A.A … a rose.”

Blank and Vere-Composition, from Collected works, 1974–1978, video stills © Ernest Gusella

In the early 1980s, Gusella’s video work moved away from performances in the studio into what has been described variously as “electronic dreamscapes”[10] and “curdled counterculturalism.”[11] During this period Gusella traveled extensively with his wife, Tomiyo Sasaki, also a video artist, screening work in Europe and Japan. Gusella described What Under the Sun (1984), inspired by a trip to Mexico, and other tapes from this period such as The Red Star (1986) as “electronic stream of consciousness techniques”[12] now applied to specific topics. A major traveling video exhibition on comedy and humor curated by John Minkowsky (Media Study/Buffalo, 1984) included Gusella’s video work and also excerpts from two albums recorded on Earwax Records, Japanese Twins and White Man (1977) and The Lone Arranger Writhes Again (1980), where Gusella played all the instruments, performed all the vocals, and wrote all the songs. In a 1979 statement, Gusella reflects on his early artistic influences and travels with characteristic puckish humor: “My work is 1/4 fornicalia funk, 1/4 New York punk, 1/4 European bunk, and 1/4 Canadian skunk.”[13]

Portrait, Playing Catch I and Playing Catch II, from Collected works, 1974–1978, video stills © Ernest Gusella

In his mid-1970s work, Gusella is attentive to multiple languages. His high and low cultural references shape word pieces that are Dadaist romps, exercises that claim permission to be playful—and not necessarily make sense. The pieces in Collected Works 1974–78, however, also perform a sophisticated structural electronic language using waveforms, frequencies, and voltages. At its best, Gusella’s work offers coy perceptual puzzles featuring multiple inverse functions—positive and/or negative images, gestures of occlusion and/or revelation. Furthermore, these projects create absorbing spatial illusions that engage the logic of constructed two-dimensional electronic spaces which may appear to contradict the more familiar logic of physical space delivered by lens-based instruments. Dan Sandin, an important electronic tool designer speaking at an electronic arts conference (Buffalo, 1977), described the analogue video synthesizers of this period as providing the first generation of video artists with opportunities for “high tactility: a direct relationship between what the hand does and what the eye sees.”[14] Gusella’s work not only demonstrates this tactility but often uses this hand/eye immediacy like a magician to playfully tease the viewer.

Pistol and Two Figures, from Collected works, 1974–1978, video stills © Ernest Gusella

In the radically shifting cultural terrain of the 1960s and 70s, German curator Wolfgang Becker’s enthusiasm for identifying “the imminent expression of a specific generation’s attitude to life”[15] supported the vision of the Neue Galerie in Aachen and Peter and Irene Ludwig’s collections of contemporary art. Becker was also interested in early video art, and attended to work such as Gusella’s performative electronic investigations, which relished the open terrain of a new medium. Becker’s early and ongoing curatorial investments in experimental forms, performance, and “restlessness” as “a cultural conviction”[16] also inform a critical context for work now housed in the Ludwig Forum Video Archive, an accessible resource for visitors and committed cultural researchers.

[1] Ernest Gusella. “A Statement on Early Works with Oscillators.” Vasulka Archive: n.p. Accessed Feb. 26, 2017. [https://vasulka.org/archive/Artists2/Gusella,Ernest/general.pdf]

[2] Julia Dzwonkoski and Kye Potter. “‘I’m Not a Believer’: Interview with Ernest Gusella.” The Sky Opened Up with Answers. Paris: onestar press, 2009,75.

[3] Chris Hill. “Interview with Woody Vasulka.” The Squealer [Buffalo Media Resources]: n.p. 1996.

[4] Chris Hill. “Performance of Video Imaging Tools.” Rewind. Ed. Chris Hill. Video Data Bank, 1996, 37 (DVD).

[5] Ernest Gusella. “A Statement of Video” (March, 1979). Histories and Theories of Intermedia. Feb. 5, 2008. Accessed Feb. 26, 2017. [https://umintermediai501.blogspot.com/search?q=ernest+gusella]

[6] John Minkowsky. “Tapes by 1979–90 Award Recipients in Video, Creative Artists Public Service Program in New York State.” Vasulka Archive: n. p. Accessed Feb. 26, 2017. [https://vasulka.org/archive/Artists2/Gusella,Ernest/articles.pdf]

[7] Dzwonkoski and Potter. op. cit., 77.

[8] Ibid, 78.

[9] Davidson Gigliotti. “Words and Images, Images and Words.” The Soho Weekly News, November 4, 1976.

[10] Michael Gitlin. “Video: Approaching Independents,” Film Library Quarterly. Vol. 17, No. 1, 1984.

[11] J. Hoberman. “All Work and Some Plays.” The Village Voice, Vol. 27, No. 28, July 13, 1982.

[12] Ernest Gusella. “What Under the Sun.” 1984. Vasulka Archive: n. p. Accessed Feb. 26, 2017. [https://vasulka.org/archive/Artists2/Gusella,Ernest/WhatUnderSun.pdf ]

[13] Gusella, op. cit. (1979).

[14] Kathy High, Sherry Miller Hocking, and Mona Jimenez. Emergence of Video Processing Tools, Volume 2. Chicago: Intellect, Ltd., 2014, 400.

[15] Ludwig Forum Aachen, “The History of the Ludwig Forum,” 2017. Accessed Feb. 26, 2017. [https://ludwigforum.de/en/museum/history/ ]

[16] Eckhart Hoog. “Wolfgang Becker’s Motto Is: Restlessness!” Aachener Zeitung, Oct. 8, 2016. Accessed Feb. 26, 2017. [https://translate.google.com/translate?hl=en&sl=de&u=https://www.aachener-zeitung.de/news/kultur/wolfgang-beckers-lebensmotto-lautet-unruhe-stiften-1.1465463&prev ]