Carla Schulz-Hoffmann on

Barbara Hammann

The early works of Barbara Hammann are already fascinating in how they find a balance between precise execution and an open-ended approach. And they capture our attention through their careful exploration of opposites like closeness and distance, repose and movement, fullness and emptiness, but even more decisively through the fundamental existential questions they broach. Again and again they formulate anew the hope for a degree of certainty and permanence within the fleetingness of time and space, light and sound, becoming and passing. The works created between 1981 and 1986, documented in the Aachen collection, are exemplary in this respect, containing essential aspects of her complex approach.[1]

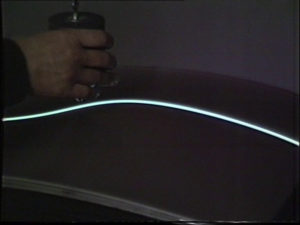

Neue Welle, 1981-83, in: Videoinstallationen 1981–1986, 1987, video stills © Barbara Hammann, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Neue Welle (New Wave, 1981-83)[2] for example explores, almost in passing, the laws of attraction and repulsion, of relationships and their manipulation. The artist says that she still finds this work convincing today because it is geared to getting viewers to participate. They can “playfully” influence the bright line of white light running across a row of television screens, which “solely through viewer intervention changes into a wave which gradually weakens due to the mechanical friction of the pendulum swing and only intensifies again when it is once again set swinging. I never wanted any kind of ‘mechanical’ control.

Barbara Hammann, Neue Welle, Nationalgalerie Berlin, 1983, © Barbara Hammann, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, photo: Waltraud Krase

Everyone can experience the beauty of the basic laws of physics that define our world, which often remain hidden until they shine forth.”[3] It also becomes quickly apparent here that there is a fine line between control and loss of control. It is only the initial impulse that comes from us; the further course is taken immediately out of our hands, and we are no longer capable of calculating the path. Who or what is being manipulated here? Doesn’t our role already change here between these poles? We believe we are in control of events but suddenly are forced to realize that all we have done is contribute a peripheral Impulse.

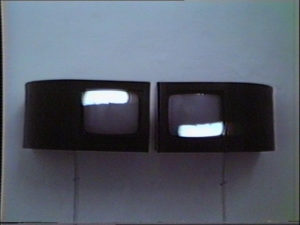

Katla – Schwarzes Instrument, 1985, in: Videoinstallationen 1981–1986, 1987, video stills © Barbara Hammann, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Katla – Schwarzes Instrument (Katla – Black Instrument, 1985),[4] developed for the exhibition Zugehend auf eine Biennale des Friedens in Hamburg,[5] initiated by Robert Filliou, underlines essential aspects of these observations. The video object, mounted high on the wall, changes from a circular into a funnel form, which the visitor, depending on his height, can look into, perhaps forced to stand on tippy-toes but in any case fully alone and with eyes focused on the opening. “You have to line up to be able to look in. The Black Instrument can only be experienced visually and acoustically as a whole by one person at a time. […] Looking down into the depths is unusual because you are separated from your surroundings and catch sight of a thumb and index finger opening and closing, a body image that acts as a metaphor for our polarities: to be self-contained, residing in oneself, peaceable in nature, and the opening, the movement outward that can rise into aggressiveness, intensified by the sound when you press your ear against the peephole of the cylinder.”[6] Here, too, experiencing the work presupposes that one isolates oneself but at the same time is fully exposed. And what shows itself in the funnel develops a disturbing internal dynamic, mutates into surreal dream figures. Through the extreme slowing down, the hand monotonously “cutting” with its thumb and index finger takes on new meanings, ever transforming, even into monstrous body forms.

Closed Circuit, 1984, in: Videoinstallationen 1981–1986, 1987, video stills © Barbara Hammann, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

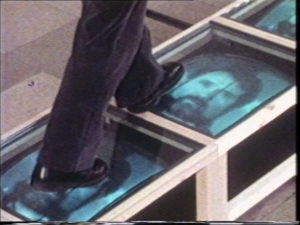

A conscious decision is also demanded when engaging with the video installation Closed Circuit (1984).[7] To experience the installation, one has to step into the circle formed by eight color television sets lying on the floor. From above, the viewer looks down on a blazing pulsating ring of light[8] that exerts a magical pull. It is difficult to escape its fascination, even if a sense of danger subliminally looms. One senses physically that “closed systems” generate “catastrophes,” but the pull of the “powerful aesthetic fascination” is too great.[9] Once again it is the visually experienced tension between contrary sensations that lends this work its special attraction: The vague feeling of being helplessly exposed to an inevitable threat mingles with the desire to nevertheless enjoy to the full what is happening in its optically seductive presence. At the same time however, the viewer must be willing to take this step, directing a concentrated gaze downwards into the mysterious crater. As soon as he looks out over the edge, this fixation is loosened. In contrast, Walking on Yourself (1984)[10] brings viewers into a situation where they indeed walk on themselves. The viewer crosses a bridge made up of five television sets, which are simultaneously showing, thanks to a camera, his image. Here the artist is offering, first, an ironic commentary on a media reality that rigorously excludes any identification and intimacy between image and viewers on the one hand, turning them into voyeurs of a reality they are alienated from, while on the other hand, however, the self-image and media-based communication forms suggest an omnipresent intimacy that remains physically ungraspable. Immediately, irritation and uncertainty become palpable: Who could feel any different when they walk on themselves? Secondly, Hammann is putting into practice here her idea of “non-violent” interaction with our surroundings, for we are at once perpetrator and victim, so that manipulation is not primarily “forced onto” someone else, but we “experience” it on ourselves, we are the ones “carrying out” an act of violence.

Walking on Yourself, 1984, in: Videoinstallationen 1981–1986, 1987, video stills © Barbara Hammann, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

In this “lived-out” position, Barbara Hammann is comparable to Bruce Nauman. He too undertakes experimental field research on fundamental psychological and physical sensitivities, or explores the relationship between language and reality with his own body. Moreover, the protagonists of his work are not just friends, acquaintances, or objects, but he also involves himself. And similarly to Barbara Hammann, the function of the viewer varies—he can be in front of or inside a respective work, has to move into and around it so as to experience it. But here the parallels end, for unlike Hammann, Nauman is uncompromising in his aspiration to create confrontation. One is fully at the mercy of his works and, once involved, can decide only either to “refuse” or “endure” a threatening, uncomfortable, aggressive, or indeed monotonous situation. Nauman’s works activate emotions; they are disturbing and often border on what is bearable. Nauman has described his method as taking up the one practiced by the blind bebop pianist Lenny Tristano: “When Lenny played well, he hit you hard and he kept going until he finished. […] From the beginning I was trying to see if I could make art that did that. Art that was just there all at once. Like getting hit in the face with a baseball bat. Or better, like getting hit in the back of the neck. You never see it coming; it just knocks you down.”[11]

Paula und Marianne, 1987, video stills © Barbara Hammann, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, Christoph Wirsing (documentation)

This statement marks the line clearly distinguishing Barbara Hammann from Bruce Nauman. She never seeks to confront viewers with an extreme situation that has no way out and uncompromisingly demands that they take a position on what takes place. Instead, Hammann seeks to show “how one approaches things, how one deals with them, does not possess, seize, mutilate them, but lets them be.”[12] This position is grounded in an approach that is unambiguously emancipatory: Barbara Hammann is always concerned with redefining the place of the individual in society, with rupturing and opening entrenched norms that restrict the individual and forcibly impose expectations from the outside. While she always begins concretely from her role as a woman in society, she increasingly queries the relationship of the individual to his surroundings in general. And that she explores this frequently with regard to herself shows the seriousness behind her artistic practice. Typically, she is thus to be found as a “visual model” in numerous videotapes, Polaroid shots, and video installations: Through gestures, mimicry, her voice, and/or the movements of her body, she places herself in relationship to a protagonist. One fascinating work that offers a finely differentiated realization of this approach is the video theater Paula und Marianne (Paula and Marianne, 1987),[13] of which the Aachen collection has a 24-minute documentation. The catalyst for this complex project was a scholarship from the Barkenhoff Stiftung in Worpswede in 1987 that brought with it an intensive study of Paula Modersohn-Becker, in many respects an immersion in her life and surroundings: “Her presence became extremely strong for me. I admired the radicalism, simplicity, and love in her work and life.”[14] When Hammann then received an invitation to produce a video,[15] the focus was immediately clear: It was to be on Paula, her problems and her role as an artist, themes that also move Barbara Hammann and in which many aspects of her own situation in life are mirrored. She chose Marianne von Werefkin to be the counterpart and “elective affinity” pole in the performative video work, for her Letters Incognito[16] “had moved me deeply in their power and vulnerability, despair and visionary intelligence.”[17] In a fictive “live dialogue,” Barbara Hammann—as Paula Modersohn— and her friend the artist Brigitte Niklas as Marianne von Werefkin stand opposite one another and in a pointedly calm, almost emotionless style recite passages from their letters.[18] “I was interested in their ideas and thoughts as part of their artistic identities. The inherent qualities of the video medium enabled me to create a contemporary aesthetic and mental space. First of all through the immaterial aspect—quality of light—secondly through the ‘closed circuit system,’ the immediate overall presence of the fragmented self (the face) in space and time, the difference of past and present is abolished…”[19] Through the abolishment of differentiations in time, the placelessness and the shifting of identities, the persons and what they say weave together into an inextricable web, into mirroring facets in a chain of possibilities. A sense for the multilayered complexity of the project is only truly gained when this scenario is imagined in the real form of the video theater with its performers, their “video shoes” (shoes with monitors) illuminating the space in blue and yellow, the video screens, and the visitors, i.e., just as the piece was performed in 1987 in Munich. Paula und Marianne becomes a place of endless openness, indeed, of freedom, reciprocal mirroring, and changes in perspective.

Barbara Hammann, Katla – Schwarzes Instrument in the exhibition Zugehend auf eine Biennale des Friedens, Hamburg, 1985, © Barbara Hammann, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, photo: private; Barbara Hammann, Katla – Schwarzes Instrument, view into the cone, in the exhibition Zugehend auf eine Biennale des Friedens, Hamburg, 1985, © Barbara Hammann, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, photo: Barbara Hammann; Barbara Hammann, Walking on Yourself, Kunstverein München, 1984, © Barbara Hammann, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, photo: private

But even quite banal actions, like peeling an orange (Eating Jaffa TV, 1979),[20] can trigger a multilayered dialogue with the world in which the most diverse associations are possible. The aggressive act of peeling an orange, a process of destruction that simultaneously contributes to the peeler’s well-being, summons thoughts of the carelessness of an affluent society that plays with food products, “mashes” them up much like a child. For all its subtle wit, the act takes on something painful, turning into a metaphor for the superficial and dominating way of dealing with the things of everyday life.

Mr. and Mrs. Poe in Island – on perversity, 1982, in: Videoinstallationen 1981–1986, 1987, video stills © Barbara Hammann, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

With very different means, but in terms of their consequential use quite comparable, Mr. and Mrs. Poe in Island – on perversity (1982)[21] explores the relativity of perception and the intensity of feelings: slowness as tender closeness, encountering and standing still as an experience of the borderline situation of life and death. The work is based on a text by Edgar Allan Poe on the hypnotizing of a person who is dying, which is mixed into the murmuring sound of a stream. “The images and sounds, in an endless possibility of combinations, come and go, comparable to the state when one is falling asleep.”[22] Played in a non-synchronized tempo, the two tapes are placed next to one another, one showing the head of woman, the other primeval landscapes, a black lava flow or a river. With their switching based on a random principle, the tapes generate a rhythm of movement that is undefined in its single moments, hangs—as it were—in the balance. This corresponds to the juxtaposition of different sound information: While the woman reads the Poe text, we simultaneously hear the diffuse sound of the river. This suggests to perception an indefinite state between being awake and dreaming, one in which nothing has yet assumed a concrete form, so that anything still seems possible. The images mingle in the viewer’s mind, without fixating him and themselves, for they remain ungraspable, elusive. A state of poised uncertainty reigns between form and formlessness, between the passing of time and timelessness, but also evoking dissolution and self-forgetfulness, which absorbs the individual. In The balance of what? – Arleen Schloss (1986)[23] this approach is potentiated. In an endless loop, two giant thumbs, mirrored against one another, try to find balance. They “mark the passage from movement to equilibrium=standstill=death”[24] and then begin anew.

The balance of what? – Arleen Schloss, 1986, in: Videoinstallationen 1981–1986, 1987, video stills © Barbara Hammann, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

In contrast, Dim Sum – a little touch of heart (1985)[25] shows with endearing melancholy the closeness of contrary emotions. A color television set, its screen facing upward, lies in a black fishing net that hangs from the ceiling. The face of a laughing woman with a red mouth can be seen, and now and then it seems as if she is on the verge of crying. As deftly practiced by advertising for decades, an image is then interspersed for a split second, a view from above into a pram that entrenches itself intensively in the subconscious and triggers a longing for its “possession.” Whereas advertising uses this method to subliminally suggest thirst or hunger for a specific product that alone could satisfy this need, here an internal relationship is imperceptibly produced between the woman’s face and the child. Is the adult, in a mixture of serenity and melancholy, remembering an infant’s feeling of security? Does the face express happiness at having had this feeling, the sorrow felt at its irretrievable loss or indeed at never really having known it?

Dim Sum – a little touch of heart, 1985, in: Videoinstallationen 1981–1986, 1987, video stills © Barbara Hammann, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

This balance between different emotional states has always been characteristic of Barbara Hammann’s works and has remained so down to the present day. The enormous potential of the works resides in the symbiosis, ceaselessly astonishing in how it comes together, in the “overall sound” of movement, space, and—increasingly in the course of her evolution as an artist—audio, a sound resonating with all of the senses without resorting to manipulation. To achieve this, Barbara Hammann uses various experimental methods, connects classical with avant-garde elements, links the most diverse genres, and dares to take unconventional , literary and musical paths.[26]

It is this synthesis of free improvisation and structure that is convincing, although—as this look at her early works has shown—the artist trusts to a special degree in the willingness of the viewer to “become engaged,” to be open to an unbiased involvement. Her works refuse to entertain passivity, an interest-less pleasure; they would then remain nothing but incomprehensible single particles. The chance lies, rather, precisely in their openness, in the refusal to manipulate the viewer while thus giving him at the same time the possibility to tune into, anew and impartially, the perceptual potential offered, into the “overall sound.” It is in a way the opportunity to see oneself anew again and again, and to realize, comparable with the definition given by Henri Bergson, that, “for a conscious being, to exist is to change, to change is to mature, to mature is to go on creating oneself endlessly.”[27] In this sense, the “Closed Circuit” is not an inevitable end but implicates the possibility of an “Open Ending.”

[1] The artist was also represented at the 40th annual exhibition of the Deutscher Künstlerbund at the Ludwig Forum with the work Nest für Dachau, 1991, metal object with color television set, meandering cable, VHS player.

[2] Neue Welle (Pendel), 1981–83, installation, two to five black-and-white television sets with a horizontal deflection manipulated into a line of light, participatory magnetic pendulum, Lothringerstr. 13, Haus der Kunst and Lenbachhaus Munich, Nationalgalerie Berlin.

[3] Barbara Hammann, quoted from correspondence with the author in the spring of 2017. The work changes depending on the size of the exhibition space used for the installation, which determines the brightness of the line of light.

[4] Katla – Schwarzes Instrument, 1985, single-channel video object, black-and-white monitor, screen facing upwards in a black PVC unit. The draft drawing of Katla was exhibited at the Kunstverein Hamburg. “Katla” is one of Iceland’s most active volcanoes. The name is derived from “ketill,” meaning “cauldron.” “Ketill” is also a common woman’s name in Iceland.

[5] Robert Filliou, Zugehend auf eine Biennale des Friedens, December 1, 1985 to January 12, 1986, Kunsthaus and Kunstverein Hamburg.

[6] Barbara Hammann, see note 3.

[7] Closed Circuit, 1984, single-channel video installation, seven color television sets arranged in a circle on the floor, screens facing inward, Museum Villa Stuck, Munich.

[8] The ring of light is created through the feedback of the electronically generated image “in the form of a flaming aura”; Barbara Hammann, see note 3.

[9] Barbara Hammann, see note 3.

[10] Walking on Yourself, 1984, closed-circuit video installation, black-and-white camera, five black-and-white television sets, wood construction, security glass, no installation tape, Kunstverein Munich. The work changes depending on the size of the exhibition space used for the installation.

[11] Bruce Nauman in an interview with Ian Wallace and Russell Keziere on October 9, 1978, quoted in Please Pay Attention Please: Bruce Nauman’s Words. Writings and Interviews. ed. J. Kaynack, Cambridge, MA, 2003, 320.

[12] Barbara Hammann, in: touch and go, exh. cat., Berlin 1989, n.p.

[13] Paula und Marianne, 1987, video theater, proT – Halle Munich, two protagonists, two pairs of video shoes with feedback, cable, one VHS player, two closed-circuit cameras, one control color television set for each protagonist; one spotlight each. Live transmission to six color television sets on the walls. One color television set with playback tape. Two color television sets on the stage ramp, loop, 8’00 min. Laser projection with text and horizontal line of light.

[14] Barbara Hammann, “The body as a reservoir of endless possibilities,” in: Ruimte, no. 3, 1992, vol. 9, quarterly, Amsterdam 1992.

[15] Alexeji Sagerer invited her to contribute a piece to the VIER TAGEN DES UNMITTELBAREN THEATERS in the proT-Halle Munich.

[16] Marianne von Werefkin, Briefe an einen Unbekannten (written in French as a kind of diary, Lettres a un Inconnu), 1901–05, edited by Clemens Weiler, Cologne 1960.

[17] Barbara Hammann, see note 14.

[18] The texts by Paula Modersohn are mainly passages taken from letters she wrote to her husband Otto Modersohn, published in: Paula Modersohn-Becker, Briefe und Tagebuchblätter, ed. Sophie Dorothea Gallwitz, Munich 1920. The texts of Marianne von Werefkin are taken from the Briefe an einen Unbekannten, see note 16.

[19] Barbara Hammann, see note 14.

[20] Eating Jaffa TV, 1979, color, sound, 11’00 min, color/b&w, sound, 15’55 min, two versions, one black—and white, one color (no documentation of this in the Aachen collection).

[21] Mr. and Mrs. Poe in Island – on perversity, 1982, dual-channel video installation, 1982, two color monitors, left portrait: 21’10 min., color, sound [Roni Horn reads E. A. Poe], Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus, Munich.

[22] Barbara Hammann, see note 3.

[23] The balance of what? – Arleen Schloss, 1986, single-channel video object, two black-and-white television sets, one turned 180 degrees in a two-part black PVC object, Kunstverein Oberhausen; Staatsgalerie Moderner Kunst, Munich.

[24] Barbara Hammann, see note 3.

[25] Dim Sum – a little touch of heart, 1985, single-channel video installation, color television set with screen facing upward in black fishing net hanging from the ceiling, installation tape: video pattern, 1984, 3’00 min. loop, color, sound, see no. XII in video pieces, Living Art Museum Reykjavik.

[26] Here it should be noted that Barbara Hammann studied violin and flute and played in an orchestra for a number of years. As she herself emphasizes, music was always “‘number one.’ In my works I try to attain an overall sound that treats all three levels.” She is referring here to sound, movement, and space “as being equally important.” (quoted from a letter by Barbara Hammann to the author, dated February 16, 2016).

[27] Henri Bergson: “…nous trouvons que, pour un être conscient,exister consiste à changer, changer à se mûrier à se créer indéfiniment soi-même,” in: L’évolution créatrice, Paris 1911, 8; English from Arthur Mitchell’s 1911 translation of Creative Evolution published in New York, 7.