The Video Archive, the Research Project and the Website

FOREWORD

The funding initiative “Forschung in Museen” (“Research in Museums”) launched by the Volkswagen Foundation came at precisely the right time for the Ludwig Forum für Internationale Kunst. Appointed to the post of director in 2009, Brigitte Franzen was keen to once again establish the museum as a place of research and she systematically considered the possibilities the Ludwig Forum offered in this respect. Two historically relevant fields in particular were immediately obvious: the early interest shown by the institution in video art since the 1970s and the special history of contemporary art around 1970 and its connection to the Ludwig Collection. Exhibitions[1] exploring both thematic fields were staged and two research projects, supported by third-party funding, were initiated. Since 2012, the “Plattform Aachen” has established an archive dedicated to local art history that is international in its relevance and perspective, while thanks to the project funding provided by the Volkswagen Foundation, the “Video Archive” has since 2012 undertaken the scholarly analysis, research, and presentation of the Ludwig Forum’s holdings of historical video works.

The special closeness to the research topic, namely the art objects, is what makes research at a museum so unique. It is possible to examine and study the works concretely, become intimately familiar with their historical and contemporary contexts, the archival holdings and source materials, and indeed, in the case of art post-1960, very often enter into direct dialogue with the artists. When researching in a museum, questions of conservation and restoration, exhibition practice and theory, art history and theories of aesthetics exist side by side.

Up until this point in time only rudimentarily indexed and analyzed, the video art collection at the Ludwig Forum für Internationale Kunst was ideal for such an exemplary project due to its size and the condition of the works; moreover, there were obvious but important lines of questioning that could be addressed concerning exhibition practices. This triad of research, conservation, and exhibition was then underpinned by the conceptual methodological pillars and selecting the respective cooperation partners. With the Zentrum für Kunst und Medien in Karlsruhe, in particular Christoph Blase and the Labor für antiquierte Videosysteme (Laboratory for Antiquated Video Systems) he founded, we knew that we had one of the best partners imaginable for the conservational indexing of the collection and making it once again accessible and visible. With the Institute of Art History at Cologne University and Ursula Frohne as partner, we were able to fruitfully pass on our research results to students and inject them into the latest research. This also entailed allowing students to be integrated into the project on site in Aachen in a diverse number of ways. Over the course of five years, almost thirty students and newly qualified graduates took part in the project. The two accompanying exhibition series, Videoarchiv and Videozone, presented the most recent results to the general public and brought this focal point of the collection to the attention of museum visitors in innovative ways.

The result: the complete digitization of the video art holdings, a scholarly-standard databank with viewing facilities in the library of the Ludwig Forum für Internationale Kunst, an international network of cooperation partners and institutions, a publication series organized around thematic and geographic aspects and featuring the collection’s works, as well as this website, which makes the key findings of the five-year project accessible worldwide and free of charge. All is now set for others to continue to work on and with the collection.

THE VIDEO ARCHIVE

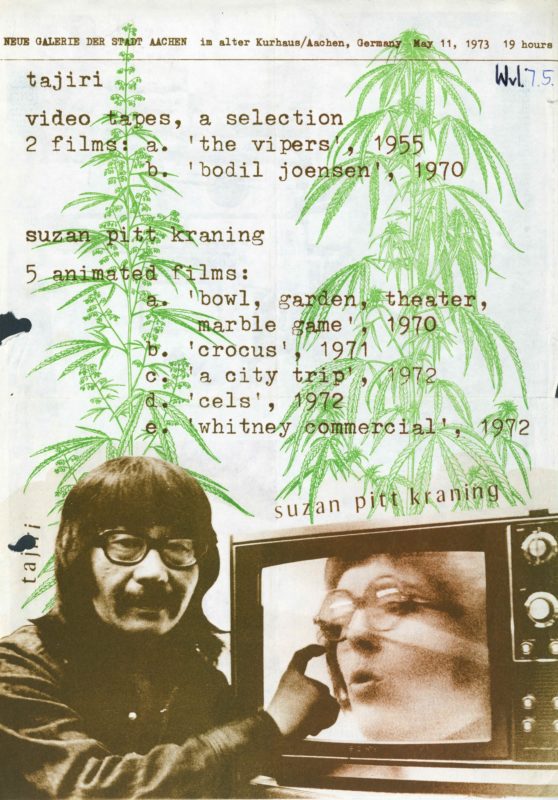

Artists experimenting with the emerging video technology were featured unusually early at the Neue Galerie – Sammlung Ludwig (1979–1990), the predecessor of the Ludwig Forum für Internationale Kunst. Their works laid the foundation for the Video Archive, which today encompasses 197 videotapes and includes numerous key works by video pioneers from the USA, Germany, Japan, and Belgium, as well as remarkably rare tapes and video recordings of performances, talks, and concerts.

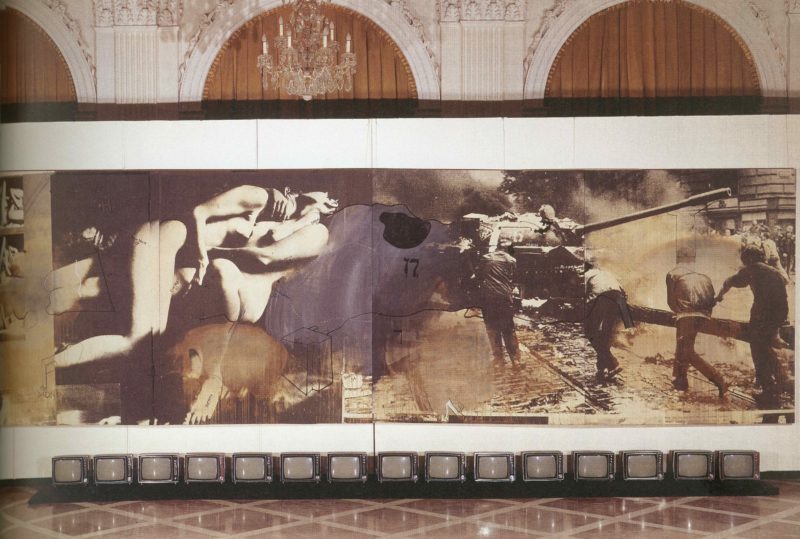

The acquisition of Wolf Vostell’s monumental video installation Heuschrecken (Locusts, 1970), a decision Peter Ludwig made during the exhibition Wolf Vostell – Elektronisch, marks the beginning of collecting video art. The Neue Galerie can be described as the first exhibition venue in North Rhine-Westphalia to prove a programmatic interest in the new medium by purchasing video art.[2] The driving force behind this early involvement with video was however not the collectors Peter and Irene Ludwig but the founding director of the Neue Galerie, Wolfgang Becker, who financed almost all the acquisitions by drawing on public funding from the city authorities and garnering the support of the friends’ society, „Verein der Freunde der Neuen Galerie“—thus building up the Video Archive as the only independent section of the museum alongside the Ludwig Collection.

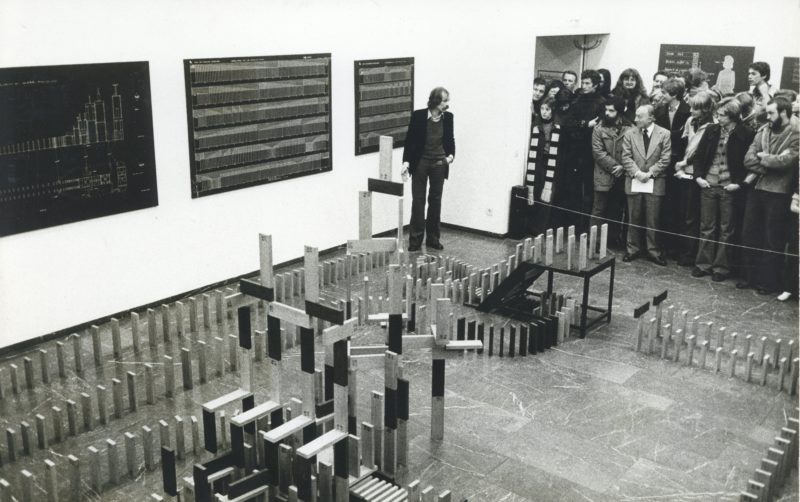

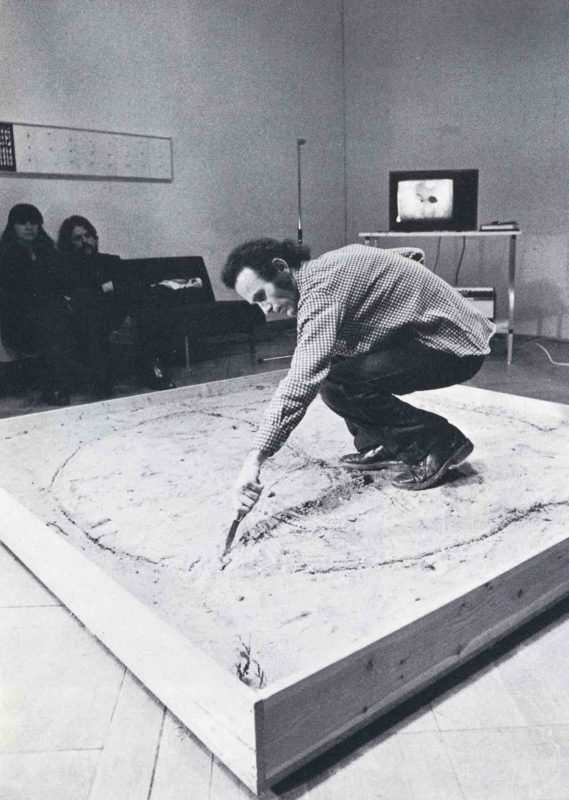

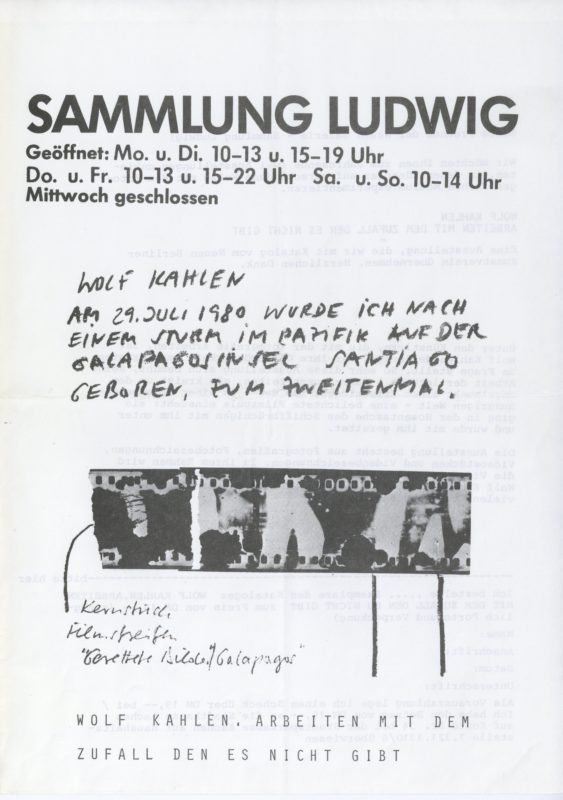

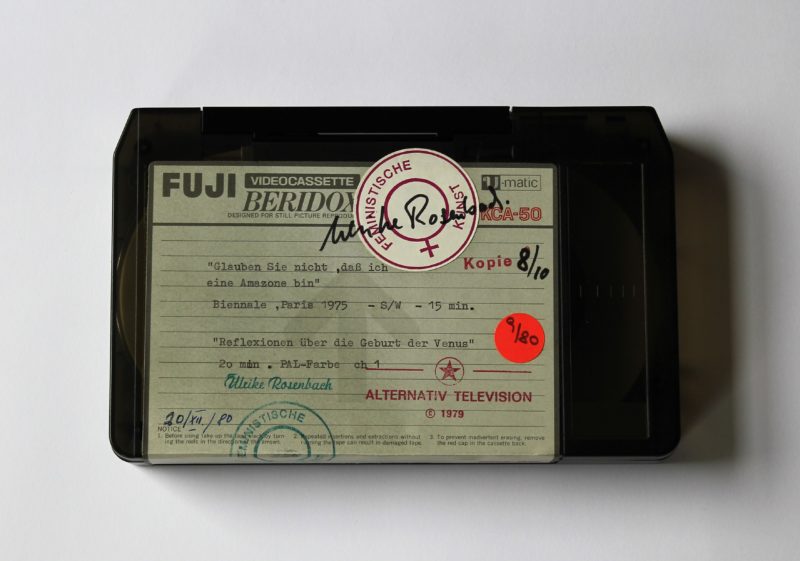

Becker invited the main players in the West German video art scene—Ulrike Rosenbach, Marcel Odenbach, Klaus vom Bruch, Wolf Kahlen, and Wolf Vostell—to Aachen for exhibitions and performances. On the initiative of the Darmstadt group Telewissen, the participatory Videotage (Video Days) took place in the Neue Galerie in 1972. Under the motto “make your own television,” Aachen’s public was invited to test out the electronic medium by making their own productions. In 1978, Becker, together with Ulrike Rosenbach and Klaus vom Bruch, hosted in the Neue Galerie the symposium Performance – ein Grenzbereich. The video documentation Rosenbach and vom Bruch made of the event as Alternativ Television (ATV), which was subsequently shown on public broadcaster WDR in 1979, is part of the Video Archive and focuses on performance as a threshold phenomenon between art, theatre, music, dance, film, painting, and sculpture. Becker not only had close ties to the most important supporters of video art in the Rhineland like Ursula Wevers, Wulf Herzogenrath, and Ingrid Oppenheim; Aachen’s geographical position close to the neighboring countries of Belgium and the Netherlands meant that he was able to establish collaborations with the Yellow Now Gallery in Liège, the ICC in Antwerp (today the MuHKA), the De Appel in Amsterdam, and the Linbaancentrum in Rotterdam, while he incorporated into the collection works by Belgian video pioneers in particular, for example Filip Francis, Florent Bex alias Hubert van Es, Jacques-Louis Nyst, and Jacques Lennep. While today these artists form their own special section in Aachen, Belgian video art is otherwise scarcely found in any other German collection. The symposium Foto-Film-Video, a cooperation project between the Neue Galerie and the Deutsch-Französischer Jugendwerk in Neuenkirchen that focused on dialogue between artists on the technological media, is documented in the Video Archive with works by Wolf Kahlen, Fritz Schwegler, Timm Ulrichs, Fabrizio Plessi, and the collectif d’art sociologique. Contacts to galleries such as Leo Castelli, Ileana Sonnabend and Ana Canepa in New York resulted in exhibitions featuring, and the acquisition of works by, US and Japanese video pioneers like Keith Sonnier, William Wegman, Peter Campus, Bruce Nauman, Joan Jonas, and Hakudo Kobayashi. Other exhibitions of the work of American artists, for example Nan Hoover and Douglas Davis, were made possible by the artist program of the DAAD (German Academic Exchange Service). The latter show also comprised an—undocumented—video performance that involved a live transmission between Aachen and New York.

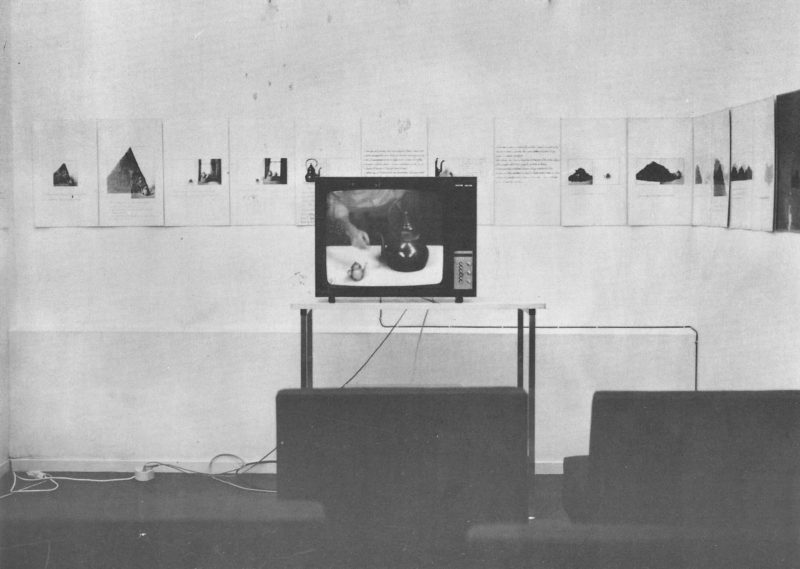

In 1981, a Videothek, or Video Library, was set up in the Neue Galerie, where twice daily a one-hour program presented selected works. This steady rhythm was soon given up however due to the lack of public response and the stress it put on the videotapes. It was by this point in time at the latest that a fully equipped studio allowed the artists to produce video works or stage video performances on site. Two deliberately informal Videogespräche reflected theoretically on video art; initiated by the Aachen art and video collector Hans Backes in 1978 and 1979 and held in the Neue Galerie, these talks brought together video artists, curators, and critics to discuss questions concerning the production, presentation, and distribution of video art.

The lively curiosity shown in the young medium is embedded in a broader context—a programmatic openness displayed by the institution towards the ephemeral, performative, and interactive art forms that were the dominating influence on the art scene in the 1970s, as well as general interest in the medium of film, expressed in the regularly held film series. That the program of the Neue Galerie was also noticed in the international video art scene is shown by how, along with Wulf Herzogenrath and Evelyn Weiß, Wolfgang Becker was the only German curator invited to take part in the path-breaking conference Open Circuits: The Future of Television (1974) held at MoMA in New York.

In response to the process of material aging of the videotapes, which entails considerable risks for playing them, measures for conserving the tapes were already being deliberated in the year the Ludwig Forum für Internationale Kunst opened, in 1991. Due to the lack of suitable alternatives to the U-matic tape at the time, these measures were initially shelved. It was not until 2004 that, with the DVD and the digital Betacam tape that had meanwhile become established as recording media for video data, an initial selection of thirty tapes was digitized in collaboration with 235 Media in Cologne. The Ludwig Forum für Internationale Kunst was thus the first German art museum to undertake concrete measures for securing the survival of tapes from the pioneering years of video art. The results were presented to the public in 2004 as part of the exhibition Video et cogito and discussed by the expert group “el_media” from the German Association of Conservators under the chairmanship of Ulrich Lang.[3] In the same year, the project 40 Jahre Videokunst in Deutschland von 1963 bis heute, initiated by the German Federal Cultural Foundation, took on the task of producing a comprehensive and detailed survey of German video art. The follow-up project Record > Again! from 2006 continued this process: Videotapes from different museum collections were digitized, analyzed, and exhibited—among them thirty-two works from the Ludwig Forum’s holdings. The presentation of the collection in the show Videoarchiv, shown at the Ludwig Forum in 2009 in parallel with Record > Again!, and the accompanying lecture series,[4] were the prelude to systematically indexing and analyzing the tapes under the title: “Videoarchiv. Die wissenschaftliche Erschließung und Präsentation der Videobestände des Ludwig Forum Aachen” (Video Archive: Scholarly Research into and Presentation of the Video Holdings of the Ludwig Forum Aachen). Another glimpse of videos in the collection that had already been digitized was afforded by the 2011 exhibition Nie wieder störungsfrei! Aachen Avant-Garde since 1964, which was presented just before the project was launched.

THE RESEARCH PROJECT

Thanks to the generous support of the Volkswagen Foundation, the digitization of the videotapes recorded on historical formats was begun in 2012 at the Laboratory for Antiquated Video Systems run by our cooperation partner the Zentrum für Kunst und Medien (ZKM) in Karlsruhe. The entire collection was secured long-term on LTO, a reliable RAID system (an established hard- and software system for archives) and additionally, for scholarly research and presentation, made available on DVD. On this basis, the 197 works in the Video Archive were analyzed by the researchers in the project (project manager/curator Miriam Lowack and researchers/curators Lou Jonas and Anna Sophia Schultz): The metadata were indexed and entered into the databank MuseumPlus, the works researched and interpreted in the context of the respective artist’s oeuvre, the provenance traced, the production context identified, the original presentation form reconstructed, comparisons made with versions in other collections, and literature and relevant archival material compiled in a reference handbook, which will be accessible to scholars for research purposes after the conclusion of the project. This fundamental work paves the way for future research on a collection that had to remain literally invisible for so long—because the original tapes could no longer be played due to the aging process of the material without endangering their very existence.

A second key focal point of the work was to identify adequate presentation forms for historical video art given the obsolescence of the original playback devices and the digitizing of the tapes—in other words, between the poles of reconstruction and staging new settings. The original players and cathode ray tube monitors are becoming increasingly rare, with both the competence and materials lacking to repair the old equipment. While some works dictate their presentation form through their use of the old monitors and sets, others are in fact updated by applying new technical apparatus. In the experimental spirit of a “research-focused curatorial practice,” this line of investigation was discussed and presented in the exhibition series Videoarchiv[5] that accompanied the project. The exhibition series looked at the conceptual and contextual aspects of presentation and the thematic fields covered by the collection and then brought these finer details to the attention of the public. A pocket-sized publication series, to which students contributed, served as an exhibition guide and documentation in one, presenting the artists and subject matter in detail. As a counterpart, the exhibition series Videozone[6] presented selected positions in contemporary art that are prime examples of current artistic and curatorial work with moving-image media and their various staging formats.

Making contact with artists, curators, contemporary witnesses, gallerists, collectors, and estate trustees was another major component in the research work, as was conducting and recording interviews, which we approached as plotting a kind of oral history of video art. The interviews focused on reconstructing the contexts of production and the original presentation for specific works and discussing possible suitable presentation forms for present-day exhibitions. Moreover, we asked about the structures, networks, conditions, dynamics, and impulses within the pioneer phase of video art. Our interest here was to reconstruct and reignite historical links and contexts that had sunken into oblivion over the years, in this way looking to establish a new network that institutions can use to position themselves in the field of video art.

As a reproducible medium, video allows both limited and unlimited editions, which are respectively tied to different forms of distribution. In particular in the late 1960s and early 1970s, artists often saw videotapes as a mere byproduct of intentionally fleeting performances, leaving them in the hands of museums without any written agreement. This circumstance makes provenance research a complex and indispensable task, one that has guided our project work from the outset.

The important question as to the visibility of the Video Archive beyond the term of the research project is something we also pondered from the start. Specific formats were devised and realized over the course of the research work, from a permanent viewing facility in the museum’s library, which since 2015 enables visitors to watch each of almost 200 video works in full length, to the presentation of the archive in temporary exhibitions, along with the possibility of preparing the archive’s holdings for the website.

The academic partnerships with Cologne University and Ursula Frohne, and with Liège University and Marc-Emmanuel Mélon, were an important impulse for some of the seminars on museum work with historical video art, held at different universities over the course of the project.[7] The close collaboration and productive exchange with the Institute of Art History at Cologne University led to numerous students and doctoral candidates working in the research project and on the final publication.

Acting as both research and exhibition venue for video art, the Ludwig Forum für Internationale Kunst was in 2015 a cooperation partner of the EUROVIDEO Festival in Liège, a competition established by the organization Videographie for young European artists working in the field of audiovisual media. Besides taking part in the jury, the Ludwig Forum presented selected competition contributions in dialogue with video works from the collection in April 2015.

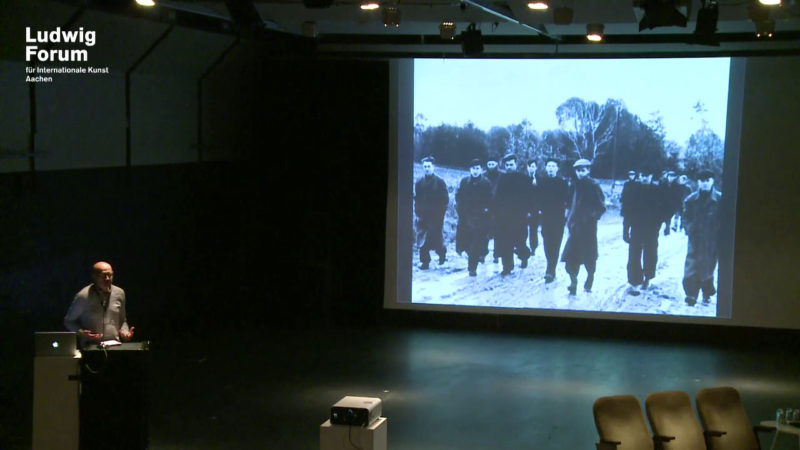

An initial conclusion to the project was the two-day international conference Video Matters held in the fall of 2015 at the Ludwig Forum für Internationale Kunst, which brought together fifteen curators, scholars, and artists from Europe and the USA active in the field of video art. The principal themes and questions that had arisen and been worked on over the course of the project were the subject of keynote lectures, short presentations, and discussions. This was followed by the panel Networking for Media Art Archiving, where the international GAMA task force (Gateway to Archives of Media Art) looked at the possibilities for networking and establishing cooperation partnerships between art academies, museums, festivals, and distributors in the field of video art.

THE WEBSITE

The present publication marks the provisional conclusion of the research project. We chose the form of a research-based website because of its inherent capability to do justice to the moving images of the audiovisual works to be presented. Moreover, because a website is a non-finalized medium, it is also capable of taking on other roles: in our case, an archive into which texts, (video) interviews, and various materials pertaining to the works of the collection can be entered; and it is ideal for establishing a platform serving the networking of institutions, artists, and estates.

The heart of the website is the “discoveries” the research team has made over the past five years: rare, exceptional, and unjustly forgotten works and materials. In addition, there are the artists whose canonical position is represented in the collection by a unique wealth and breadth of works. The works of the artists, presented under 30 Artists in Focus, are analyzed by internationally renowned experts, embedded in their specific art historical and general contemporary historical contexts, and presented in short video sequences. Almost all of the texts are illustrated with video stills from the works and complemented by historical photos documenting the production and original presentation of the videos. Short texts place the shown video sequence in its relevant context, while links make accessible further information on the artist (website of the artist, estate, foundation, etc.).

All of the tapes, including the metadata collected over the course of the project, are the basis of the timeline that places the Video Archive in both its local and international contexts. The Video Archive in Context is a survey of those events in Aachen that shaped the late 1960s phase of the burgeoning video art scene and the beginning of the collection practice at the Neue Galerie. This body of information testifies to the programmatic openness the institution has shown towards the ephemeral, performative, and interactive art forms, once again underlining the fact that the Neue Galerie – Sammlung Ludwig was one of the first institutions internationally willing to take this young medium seriously from the outset. The exhibitions, events, and (video) performances illustrate how the medium and its potential was approached and appreciated in this period of experimentation, while they also plot the genesis of a collection that responded directly to new trends. Starting from this historical juncture, the history of the collection is traced down to the present day—always against the foil of parallel international developments in this field. Short texts describe these key events and are, wherever it proved possible, complemented with photographs or archival material.

As a technology-based medium, video raises the question of what constitutes suitable presentation forms. Today there is—due to technological progress, the obsolescence of the original playback machines, and the digitization of the videotapes—a broad spectrum of possible presentation forms. But also on the level of production, reception, conservation, and distribution, as well as the collecting and exhibiting of works, approaches to the young medium have changed considerably over the course of its ongoing historization and museumization. Drawing on two discussion formats used in the Ludwig Forum, the deliberately informal “video talks” from the late 1970s and the conference Video Matters, Ursula Frohne reflects in her theoretical contribution to the website on the shifts evident in the way video art has been thought about and approached. Under Conference it is possible to view video recordings of most of the contributions to the conference held at the Ludwig Forum für Internationale Kunst in the fall of 2015.

Of inestimable value for identifying the suitable presentation form for a video work is the dialogue with the respective artist. Certain forms of presentation were not yet possible in the late 1960s and 1970s, or they were technologically and financially not really feasible, so that the decision made for one presentation form does not necessarily mean it was the one preferred over another. In an interview, Keith Sonnier expressly supports a projection of his video works in an exhibition context as a way of enhancing the impact color and light can have on the viewer. A selection of the interviews conducted by the research team over the course of the project is available under Interviews. The special importance of the founding director Wolfgang Becker in initiating and continuously expanding the video collection is detailed in a video interview from 2017 in which he speaks about the beginnings and impulses behind his collecting practice as well as the institutional and historical context.

Brigitte Franzen and Anna Sophia Schultz on behalf of the Video Archive research project team at the Ludwig Forum für Internationale Kunst

[1] These were Hyper Real, Nie wieder störungsfrei! and Nancy Graves Project, as well as Record Again and Videoarchiv.

[2] In 1971, the Krefeld Kunstmuseum followed suit, acquiring works by Klaus Rinke and Ulrich Rückriem, and then in 1974, the Wallraf-Richartz Museum / Sammlung Ludwig, Cologne, made its first purchase of 16mm films and U-matic tapes. In 1972, Günther Uecker produced in the video studio of the Folkwang Museum in Essen the work Schwarz-Weiß-Raum (Uecker-Wolleh and VMF), a documentation of the video performance that found its way into the museum’s collection. The first video work purchased by the Folkwang Museum was Ulrike Rosenbach’s I try – ich versuche, purchased the year it was made,1977.

[3] Thanks to funds from the Cultural Department of the State Chancellery (film section), it also became possible in 2008 to restore twenty-two 16mm films from the Media Collection of the Ludwig Forum für Internationale Kunst.

[4] Participating in the lecture series were Hildegund Amanshauser, Kathrin Becker, Hans-Christian Dany, Stephan Dillemuth, Barbara Engelbach, Ursula Frohne, Lene ter Haar, Wulf Herzogenrath, Susanne Jaschko, Wolf Kahlen, Elke Kania, Marcel Odenbach, and Regina Wyrwoll. The exhibition and lecture series were curated by Anna Sophia Schultz.

[5] Die Amerikaner, 2012, curated by Miriam Lowack; Elektronische Bilder malen, 2014, curated by Lou Jonas, Miriam Lowack, and Anna Sophia Schultz; and Angesichts der Kamera, 2015, curated by Jenny Dirksen and Lou Jonas.

[6] Deimantas Narkevičius, 2012, Artur Żmijewski, 2012, Wael Shawky, 2013, Almagul Menlibayeva, 2014, and Eric Baudelaire, 2015, curated by Miriam Lowack.

[7] Brigitte Franzen and Miriam Lowack, Global Groove. Frühe Videokunst Sammeln, Ausstellen, Erforschen, Cologne University, 2013/14; Brigitte Franzen, Jäger und Sammler. Die Arbeit im Kunstmuseum des 21. Jahrhunderts, Ruhr University Bochum, 2015; Lou Jonas, Video, Performance and Digital Arts, Département Arts et Sciences de la Communication, Liège University, 2015/16; Miriam Lowack, The Archival Impulse, Institut für Kunst und Kunsttheorie in cooperation with the Institute of Art History, Cologne University, 2015/16.