Silke Wittig on

Barbara and Michael Leisgen

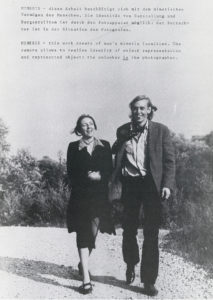

Barbara and Michael Leisgen’s oeuvre is characterized by an exploration of the interactions between humans, landscapes, nature, myths, and history. They investigate forms of aesthetic experience, perception, visual languages, and technicity, playing with the possibilities of media representation. Barbara Leisgen, born in 1940 in Gengenbach, met Michael Leisgen, born in 1944 in Spital am Pyhrn, Austria, at the Staatliche Akademie der Bildenden Künste in Karlsruhe, where both were studying painting and interdisciplinary working approaches in the 1960s. They began working as a duo in 1970. After completing their studies they moved to rural Raeren in Belgium, just on the other side of the border to Germany; in 1985 they then moved to close-by Aachen.

Barbara und Michael Leisgen

At the end of the 1960s, once they had finished their studies, they turned away from painting to experiment with the mediums of photography and video. Instead of using a sober representation when reflecting on humans and nature, they pursued a decidedly subjective approach, creating active scenes and situations. One reason they turned to the medium of photography was because they considered it—unlike the still prevailing classical disciplines of painting and sculpture—particularly suitable for conducting visual research and media-reflective experiments. In early works Barbara Leisgen herself took on the role of the rear-view figure, depicted as a mediator between heaven and earth, humans and nature—and at the same time as a bridge between the viewer and artist. Their explorations of the relationship between nature and humans draw on both the Early Romantics and the history of cosmogonic myths, and they soon tapped into one of the main thematic complexes of their work: the sun as the source of light, the symbol of life and simultaneously that of destruction, not to forget of course that it is the very basis of the photography medium itself. The first photographic technique, the heliography developed by Nicéphore Nièpce, forms its name from the Ancient Greek words for “sun” (ήλιος) and “drawing/writing” (γράφειν). Barbara and Michael Leisgen thus approach the medium of photography literally, using the sunlight to draw and paint, to capture subjects visually. Their exploration of how nature, time, and sunlight are perceived is not limited solely to photography however. Already in the early 1970s, the Leisgens discovered video as a time-based medium suitable for their artistic work, using it extensively and combining it with their photographic works to create larger installations.

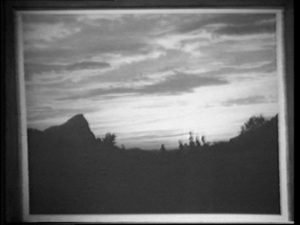

Still Life, 1970–1971, video stills © Barbara und Michael Leisgen

Created in 1970–71, the video work Still Life (10: 49 min, black-and-white, audio) explores the idea and perception of nature and landscape while reflecting on the possibilities of representing them with the mediums of photography and video. Accompanied by bird calls, the video first shows a landscape through a single camera setting for minutes on end. After around seven minutes, the camera zooms backwards, the bird calls fall silent, and the setting now takes in the picture frame surrounding the landscape, revealing it to be a representation. The spectacle of nature is shown to be an illusion, the perceived video recording of the landscape turns out to be a framed representation in a living room. Still Life is a prime example of how the artist duo always seeks to reflect on the media they deploy. Juxtaposing the media of photography and video, this work plays with the aspect of time and the audio components that make the photography seem like video, and elucidates the idea that photographs and video images can never render an objective truth—but they can generate the illusion of rendering reality, and are capable of deceiving the viewer.

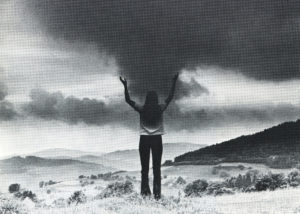

Übungen, 1972-1974, video stills © Barbara und Michael Leisgen

Übungen (Exercises, 10:38 min, black-and-white, no audio) was created in 1972–74 and is made up of two sequences, or two “exercises.” Entitled “one above the other,” the first exercise shows the artist herself, a rear-view figure in a landscape. The silhouette is positioned centrally, her arms stretched out along the contours of a chain of hills in the background forming the horizon. After a few minutes she lets her arms fall and starts walking away from the camera. The figure recedes, becoming smaller and smaller, until she finally vanishes between the hills further forward and those in the middle distance, as if she were swallowed up by the picture plane. The “second exercise” begins similarly. Again the artist is shown as a rear-view figure in a landscape setting through a single camera angle, her arms stretched out, following the contours of the landscape. And again, the figure lowers her arms after a few minutes and moves away from the camera, becoming smaller and smaller until she disappears behind a hill. The exercises were created concurrently with the important photographic series Mimetic Landscapes and Mimesis. An Ancient Greek term, “mimesis” (μίμησις) originally described the capability to generate an effect through a physical gesture. In contrast to the American exponents of Land Art, who massively intervene in the landscape to give it a new form, the works of Barbara and Michael Leisgen in this cycle tend more towards performative and experimental approaches to the relationship between body and nature. The body seems to share, shape, and augment the landscape. Like an indicator, it accentuates and complements the forms and contours of the landscape; it seems to explore it and simultaneously leave behind a fleeting trace.

Sonnenzeichen, 1973, video stills © Barbara und Michael Leisgen

Barbara and Michael Leisgen continue to explore ways of representing nature in the works that follow, in particular the theme of sun and light, as well as the power and destruction concomitant with them. The motifs recall different solar cults from mythology, for instance the Egyptian creation myth from Heliopolis, in which the solar deity Atum is considered the creator of the world, or from Greek mythology, in which the sun god Helios was worshipped. In contrast, the myth of Icarus and Daedalus presents the power of the sun as a symbol of danger and destruction. The landscape in the video work Sonnenzeichen (Sun Signs, 1973, 7:02 min, black-and-white, no audio) is dark across the lower segment, while on the horizon the contours of trees are recognizable, and the upper two-thirds show an overcast sky. The light changes constantly during the seven-minute video, the camera lens facing the low sun, which shows itself directly or indirectly depending on the movement of the clouds, so that the picture is either bathed in bright light or immersed in diffuse gray shades and gloominess. The stronger the sun, the less the landscape can be recognized, the sun and its rays the solely visible and contoured element in the respective detail. In the direct interaction between camera and sunlight, as well as the latter’s influence on the contours, the sun appears to be communicating with the camera, and so with the viewer.

Sonnenlinie, 1973-1974, video stills © Barbara und Michael Leisgen

In the later work Sonnenlinie (Sunline, 11:54 min, black-and-white, audio), a further important dimension is associated with the sun. At first, a landscape features in the left half, above it the sun surrounded by its rays, while the right remains almost completely dark. The sequence is accompanied by a rapid and regular ticking that recalls a mechanical timer and so implies another level when considering sunlight: time. How long does it take before the sun leaves behind traces of burning? How long can the camera focus directly on the sun without it scorching permanent marks? Which role does the factor of time play; when does the sun, the source of life, turn into a symbol of destruction? One-and-a-half minutes later, a dark, ring-shaped blotch forms on the image of the sun. The camera pans slowly to the left, turning the dark blotch into a line. It is as if the sun itself is burning this line as a trace into the picture surface. The camera swings so far to the left that both the landscape and the line stretch across almost the whole detail. Then the camera pans slowly back to the right again and the sun moves back along the line. The spectacle is repeated a couple of times, until the sun at last comes to a stop in the middle of the line and shines extremely brightly; the picture suddenly reverts to the negative, and the sunline, now the only light pictorial element, contrasts starkly with the dark background.

Barbara und Michael Leisgen

In fact, the duo makes use here of the light sensitivity of the vidicon tube used in video cameras, which is destroyed by the collimated radiation. Here the camera is imitating the human eye. Just as the sun produces blotches on the retina when it is directly looked at, the sunlight burns the vidicon, leaving behind a concentric dark circle that is turned into a line by moving the camera. In their later work Sonnenschriften (Sun Writings, 1978), one of their best-known work groups of photographs, Barbara and Michael Leisgen recreate the human eye’s experience of seeing and capture it in pictures. Following a fixed plan, they move the camera as if it were a brush and use the direct electromagnetic radiation, the sunlight, to reproduce its traces as symbols, letters, or incisive signs on the photographs.

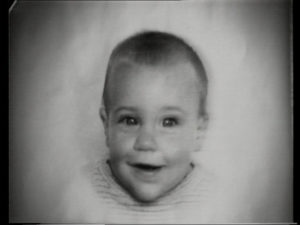

Die ersten 365 Tage aus dem Leben der L.L., 1973-74, video stills © Barbara und Michael Leisgen

Integrating video and photography is also the characteristic feature of the work Die ersten 365 Tage aus dem Leben der L.L. (The first 365 days in the life of L.L., 1973–74, 45:08 min, black-and-white, no audio). This is a collage of 365 photographs which change after just a few seconds. Barbara and Michael Leisgen took portraits of their daughter Lilli every day for the first year of her life and let viewers take part in watching how the baby begins to develop facial expressions and the changes that take place every day. When did Lilli first notice the camera, when did she begin to explore and command her surroundings, when did she begin to adapt to the world? When does the process of socialization through the family and other structures, which impacts on perception and our view of our surroundings, become discernible? The assumption that the way we perceive our surroundings is neither objective nor neutral but shaped by viewing habits and socialization processes is a fundamental thesis in the work of Barbara and Michael Leisgen. In this year-long work they dedicate themselves to pivotal questions about the influence of socialization, keeping a strict routine for shooting the material and daily observation periods. The baby’s head is shown as the central picture element, surrounded by a nimbus-like light, which in turn recalls the sun as the source of all life.

The Never Ending Water, 1974-75, video stills © Barbara und Michael Leisgen

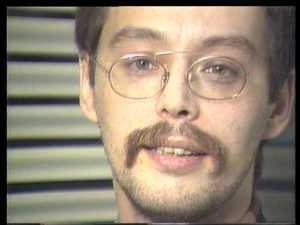

In The Never Ending Water (1974–75, 11:56 min, black-and-white, audio), Barbara Leisgen once again appears as a rear-view figure, this time however as a reflection on a water surface. At first she is scarcely recognizable through the pronounced movement of the water, but as the surface calms over the course of the video, the contours of the figure emerge more and more clearly. Barbara Leisgen moves continuously to the sound of the flowing water. At first her outstretched arms gyrate, only for her movements to gradually become gentler as the water calms; towards the end of the video, as there is barely a ripple to be seen on the surface, she holds her arms calmly by her side. Similar to the earlier works in the Mimesis group, here the artist duo demonstrates the unity between nature, body, and the camera. Nevertheless, while there are fewer links to Early Romanticism, there is an unmistakable allusion to Greek mythology: the motif of the figure reflected on a water surface is of course referring to Narcissus, and this lends the representation a particular importance. Moreover, experimenting with mirroring surfaces and reflections, and exploring the dimensions of transparency and display, are characteristic of video art in the early 1970s. Parallels to Never Ending Water are thus to be found in the work of Joan Jonas, Peter Campus, and Ulrike Rosenbach.

Un paysage près d’Ermenonville vu par une caméra, 1975, video stills © Barbara und Michael Leisgen

Unlike the other works in the Mimesis cycle, the short video Un paysage près d’Ermenonville vu par une camera (1975, 2:58 min, black-and-white, audio) shows not just the artist in the pose of a rear-view figure but the complete process behind a shooting. The camera films the duo, armed with camera and tripod, entering the Parc Jean-Jacques-Rousseau and deciding where the rear-view figure should stand. Michael Leisgen looks through the camera lens and gives Barbara Leisgen instructions on where she should position herself. The video ends with them leaving the park. Revealing the process behind production, the focus of the tape, appears somewhat surprising at first. Whereas the videos and photographs of the Mimesis cycle give the impression that the artist could influence the landscape just with her movements, give it a push, or seem to hold the sun in her hands, this disclosure as to how they are constructed demystifies the pictures. And yet, Un paysage près d’Ermenonville vu par une camera once again broaches the role of viewer and camera as an inseparable unity, an aspect that runs through all of the duo’s work. Moreover, this representation of the production process concludes the cycle of mimetic video works. New questions beckon.

Intérieur/Extérieur, 1979, video stills © Barbara und Michael Leisgen

The video Intérieur / Extérieur (13:10 min, color, audio) was created in 1979 as a commissioned work for the French-language TV show Vidéographie, devoted to promoting and presenting video art, and broadcast on the Belgian station RTBF from 1976 to 1986. The video explores Goethe’s Theory of Colors and the artificiality of pictures. Accordingly, the work, in contrast to previous videos, is now in color. A spatial arrangement is shown, made up of a stool, table, television monitor, lamp, and flower vase. The monitor is showing a sunset, which is then repeated in the background as a total view and simulates a view out into nature, only to turn out, due to the lack of any sort of movement, to be a photo wall. A voice-over reads from a French translation of Goethe’s Theory of Colors. As the effects of the individual color shades, from yellow, yellow-red, red-yellow, blue, green-blue, blue-red, purple, red-blue, red, and so on through to green, are described with great sensitivity, the coloration of the picture, with the exception of the monitor, changes to fit the respective shading mentioned. As in their earlier work Still Life (1970–71), Barbara and Michael Leisgen ironically take the manipulation of TV pictures with respect to their emotional impact to extremes, at the same time though expressing doubt and criticism of Goethe’s scientifically unprovable theory. His assumptions on the effects of colors, like the use of colors to deceive viewers with their exaggerated artificiality, are reduced to an absurdity.

Barbara Leisgen and Jean Paul Trefois producing Intérieur/Extérieur, 1979, © Barbara and Michael Leisgen

Barbara and Michael Leisgen have achieved international acclaim for their experimental photographs and videos since the early 1970s. As early as 1974, Wolfgang Becker, the founding director of the Neue Galerie – Sammlung Ludwig in Aachen, acknowledged the early work of the duo by staging a solo exhibition and bringing out a publication on the Mimesis series, soon followed by exhibitions in Belgium and France. By the time they took part in documenta 6 in Kassel (1977), the Leisgens were prominent figures in the generation of video artists who decisively shaped the medium in the 1970s. Their works were also part of the large Video Sculpture – retrospective and contemporary 1963–1989 show put on by the Kölnischer Kunstverein in 1989. The duo is popular in French-speaking countries and regions in particular for the unique aesthetic of their photography, which is seen as a counterweight to the sober typologies of Bernd and Hilla Becher. Their work has been shown from the 1970s through to the present day in a number of international museums, institutions, and galleries. After their first solo exhibition in 1974, the Neue Galerie – Sammlung Ludwig in Aachen accompanied the artistic career of the Leisgens through the work cycles that followed. After involvements in group exhibitions, the solo presentation Positional Play was held in 1987, while in 2000 the Ludwig Forum for International Art staged the first retrospective of their work with the exhibition Writing with Light – a Retrospective.